Op-Ed: I humbly submit that the Patriots’ Dark Lord Bill Belichick is (just a little bit) lovable

- Share via

In the new ESPN “30 for 30” documentary “The Two Bills,” Bill Belichick cries. You might ask yourself: What would make Belichick, the Dark Lord of the NFL who with his New England Patriots will be attempting to win a sixth Super Bowl on Sunday, against the Philadelphia Eagles, break down and weep? The thought of a deceased loved one? An onion? “Toy Story 3”?

No, Belichick is moved to tears by game tape. Scratch that: memories of game tape.

On a visit to the old Giants Stadium locker room, where he worked with Bill Parcells — the other “Bill” in the documentary — to lead the Giants to two Super Bowl titles, he recalls the hours and hours he spent in a smelly dungeon with a gaggle of overweight middle-aged men, watching the offensive line of the Houston Oilers on repeat. In this sad, ugly place, Belichick loses it.

“I’m sorry,” he says, as if he’s looking at the Sistine Chapel. “Just a lot of memories here.”

This is who Belichick is, deep down: a football grunt, a guy who strives to win but, more than anything else, yearns to watch his game tape, scheming, sketching, exercising every bit of his near-bottomless football intellect to solve the unsolvable game of football. In the documentary, Parcells says that he admires Belichick because “he has the wherewithal to maintain concentration over an extended period of time.” Right. That’s a nice way of saying he’s obsessed. During interviews, in his cutoff hoodies and cutoff shirts, Belichick looks like the most cranky coach in all of sports. And in those moments, he is — because during interviews, he is not studying football.

Everything that isn’t football — talking to a reporter, eating a sandwich, getting dressed like a normal human being — is just a painful distraction. Football is the air Belichick breathes. The rest of the world leaves him gasping.

May I humbly submit that this makes Belichick a little … lovable?

I know that Belichick and the hated Patriots have been professional sports’ bad guys for nearly 15 years now. (Although, let’s remember that you and I and everybody else were rooting for them in Super Bowl XXXVI, when they beat Kurt Warner and the Rams, even if none of us can admit that to ourselves now.) I know that we’ll all be cheering against them in this year’s Super Bowl, just like we were all cheering against them in last year’s Super Bowl. I know that the team’s quarterback, Tom Brady, is starting to approach Howard Hughes-levels of celebrity weirdness.

But there is something almost childlike in Belichick’s dedication to his chosen profession, his mad scientist pursuit to perfect his art. Belichick just wants to be left alone to play with his toys. It’s the rest of us who keep getting in the way.

Call him the Dark Lord all you want. He doesn’t care. He just wants to go back to his cave and study more film.

And this model of coach is, I think, preferable to the old guard — the Vince Lombardis, the Tom Landrys, who seemed to write their own myths as Great Men. They were the spinners of the big stem-winding halftime speeches, the When They Were Men Men that made football look like some larger-than-life pursuit, the ultimate gauge of one’s worth and merit.

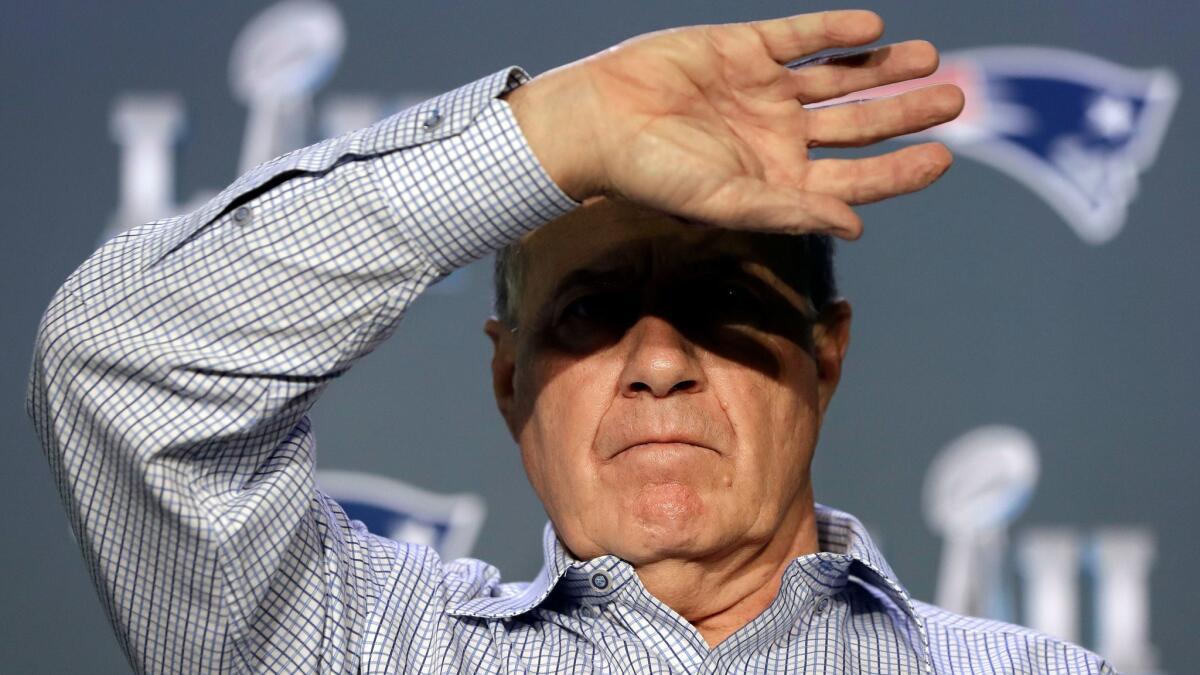

There is nothing larger than life about Belichick: He can look like a naked mole rat when exposed to sunlight. (The ESPN documentary features several shots of a young Belichick wearing short shorts and it’s … disturbing.) Lombardi and Landry may have stood for what the NFL wanted itself to look like, but Belichick is what it actually is, at least today: Sad old men in dark rooms sleeping three hours a night on couches covered in Cheetos.

The life of a modern football coach is misery — process-oriented, wonkish, crumb-stained wretch misery — and no one exemplifies that misery better than Belichick. After one of the biggest, most improbable wins of his career in the January conference championships, Belichick appeared to be wearing a trash bag.

We can hate him for his success. But we also might pity him. When we look at Belichick, we see what the coaching profession does to human beings, if they choose not to hide it. We see, more precisely, what our intense fascination with the sport, and our demands on those who work in it, does to human beings. We look at Belichick and we see what we have done. We have done this to him.

Call him the Dark Lord all you want. He doesn’t care. He’ll go back to his cave and study more film. We’ve put him on that wall. We want him on that wall. We need him on that wall.

Will Leitch is a contributor for Sports Illustrated, contributing editor for New York magazine, film critic for Grierson & Leitch and the founder of Deadspin.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.