Greg Noll, South Bay surfer and legendary big-wave rider, dies

- Share via

Far from the hotels, mai tai bars and tourists at Waikiki in Honolulu, Greg Noll sat on his surfboard beyond the frothy waves and considered his fate.

“They were horrible, absolutely horrible,” he later said of the mountains of water that rose menacing in the darkened sky, whipped up by a legendary storm in 1969. “The whole situation gave me a sick feeling.”

He could die, he reasoned. Or he could spend the rest of his life regretting the missed opportunity.

Noll paddled into the monster wave, his surfboard clattering as it sliced across the face of the beast, and then, suddenly, there was silence. Absolute silence. He was airborne, on what would become known — and forever debated — as the largest wave ridden at the time.

“When I caught that wave, I was not the same person when I walked up the beach as when I walked in the water,” he told The Times years later.

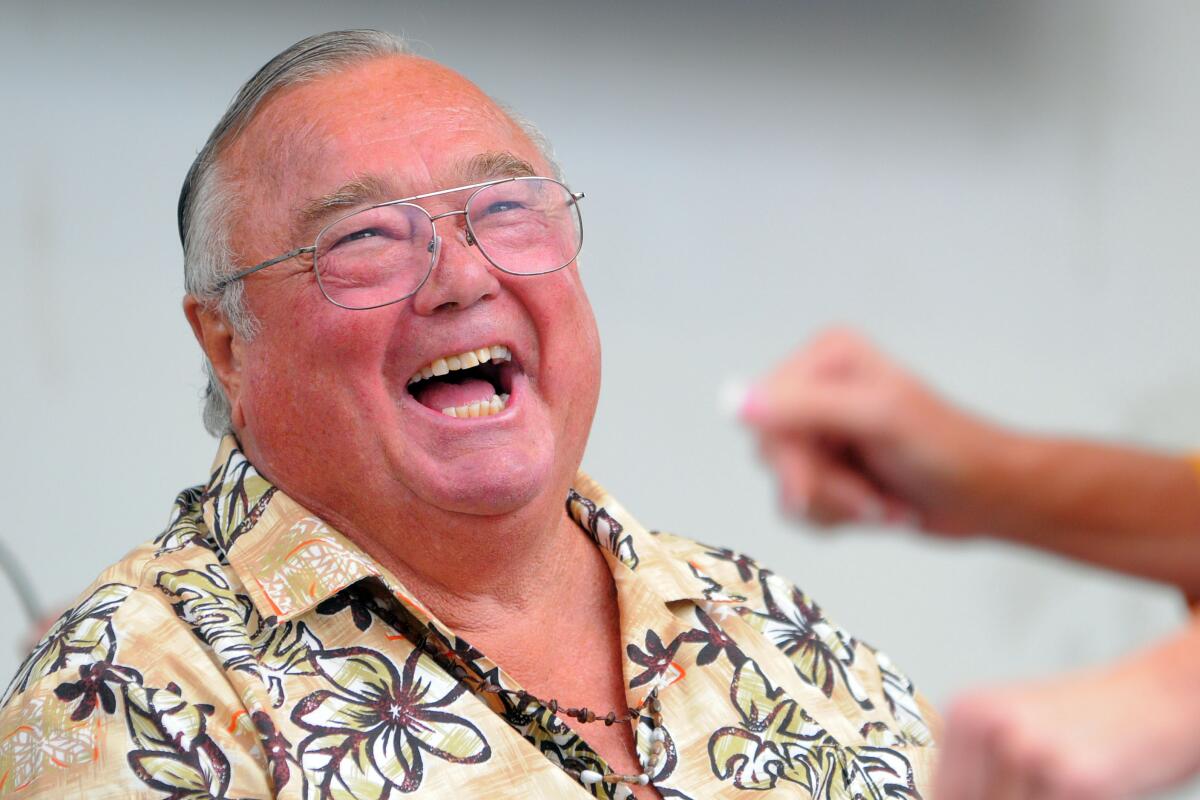

Noll, a legendary big-wave rider known for his ferocious and fearless style of challenging the sheer violence of the ocean, died Monday of natural causes, his family announced on Twitter. He was 84 and had been living in Crescent City in Northern California.

Greg Noll’s monster at Makaha was by far the biggest wave ever ridden until the tow-in era, according to surf lore. But when Stacy Peralta set out to prove it in his new film, ‘Riding Giants,’ Steve Hawk reports, the evidence simply vanished.

Gregarious with an outsize personality and salty sense of humor, Noll was also an entrepreneur who helped transform the sport with his own line of surfboards and was among the first to shape boards from balsa wood, making them lighter and easier to maneuver. But more than anything, he was a goodwill ambassador for the sport and a near mythical figure to those who sought out waves the size of freight trains.

Noll was born in San Diego on Feb. 11, 1937. His family moved to Manhattan Beach when he was 3. He was surfing by age 10, and by the time he reached his senior year in high school, he had moved to Oahu to chase the swollen winter waves on the island’s North Shore and leeward side.

At Waimea Bay, he rode waves that reared three stories in the air and was said to be the first to ride the impossibly stout waves at Pipeline. A sizable guy, Noll earned the nickname “Da Bull” for his aggressive stance on the board, leaning forward much like a defensive end set to rush the quarterback.

His reputation, already as large as he was, grew exponentially in December 1969 as the island was in the midst of a fierce winter storm that swamped roads, pushed homes off their foundation and drove boats ashore.

As Noll paddled out from the shoreline at Makaha Beach, he said, he could hear police officers on bullhorns advising residents to evacuate or take shelter. He bobbed on the water for 30 minutes thinking over his options, which were limited.

“I’d spent 20 years trying to catch a little bigger wave and a little bigger wave,” he told the Orange County Register in 2004. “It was a terrible obsession in my life. How could I live with myself if I had the opportunity present itself and I let it go?”

So he paddled fast and hard, pushed himself to his feet and dropped into a wave he estimated was 35 to 40 feet high. He could hear it exploding around him and thought to himself: If this is how I die, I’m OK with that.

The ride quickly became the stuff of legend, the size of the wave growing with every telling — 50 feet, then 60. With few witnesses and no hard evidence, it became impossible to know. Though former world champion surfer Shaun Tomson filmed Noll’s ride from a nearby rooftop, he said he later misplaced the footage.

Decades later in the 2004 documentary “Riding Giants,” filmmaker Stacy Peralta said he had unearthed several film clips and photos from that day at Makaha that seemed to verify that the giant waves in December 1969 deserved the “swell of the century” label and were probably as high as Noll had estimated.

Noll, though, grew weary of the debate, and with the arrival of tow-in surfing, in which surfers are pulled by watercraft onto waves that dwarf anything a paddle surfer could possibly reach, he believed the point was moot.

“There’s nothing that puts you to sleep faster than an old guy talking about the past,” he told The Times in 2004.

Tomson, forever coy about the missing footage, saw it slightly differently.

“I think it’s better that myths are shrouded in secrecy and the unknown,” he said. “That’s what myths are all about.”

The ride at Makaha marked the end of Noll’s career as a big-wave rider. “I just never really needed to go back out there after that,” he told the Santa Barbara Independent in 2007.

Though never far from the beach, Noll launched his own board line, opened a shop in Manhattan Beach and then one in San Clemente, and moved to Crescent City, where he was a commercial fisherman. For nearly two decades an annual surf tournament was held in the small seaside town in his honor.

Asked by the Daily Breeze whether he would change anything if he had another chance, he shook his head. Not a thing.

“It’s a neat thing to be able to look back on it and say I had a good life,” Noll said. “I owe it all back to the ocean.”

A complete list of survivors was not immediately available. Noll and his wife, Laurie, had a daughter, Ashlyne, and three sons, Jed, Tate and Rhyn.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.