A âred lineâ on Syria

President Obama has followed a commendably restrained policy in refusing to intervene militarily in Syriaâs civil war. But if the U.S. confirms that the regime of President Bashar Assad has used chemical weapons, the president should adhere to his insistence last year that such conduct would be a âred lineâ justifying action by this country, alone or in concert with other nations.

That doesnât mean the administration should accept uncritically suggestions by Israel, Britain and France that the regime has used chemical agents. As Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel said Wednesday, âSuspicions are one thing; evidence is another.â But the administration should aggressively seek the intelligence necessary to decide whether action is required, and not wait passively for others to establish the facts.

Last week, France and Britain asked the United Nations to investigate what they called credible â but not definitive â evidence that the regime has used small amounts of chemical weapons in recent months. On Tuesday Brig. Gen. Itai Brun, Israelâs top military intelligence analyst, said that Syria used chemical weapons, probably a sarin-based nerve agent, in attacks on militants last month near Aleppo and Damascus. He said the assessment was based on pictures of victims foaming at the mouth and with constricted pupils.

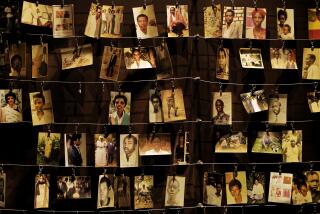

PHOTOS: Portraits of Syrian rebels

A U.S. defense official told The Times that Britain and France âdid not provide conclusive evidence of chemical weapons useâ in their request to the U.N., and the phenomena described by the Israeli general may be open to multiple interpretations.

Last August, even as he resisted the notion that the United States should intervene in Syria, Obama said that âa red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized. That would change my calculus.â And so it should. Ever since the use of mustard gas in World War I, civilized nations and the international community have condemned the use of chemical (and biological) weapons, not only because they cause mass destruction but because of their cruelty.

Granted, conventional weapons also cause death and suffering â and have done so in Syria â but the use of chemical weapons would represent a reckless escalation of Assadâs war on his own people.

An American or multilateral response should of course be proportional to the offense. That means considering whether chemical weapons were used against civilians or militants, and whether a âwhole bunchâ were used, as Obama put it, or much less. But thereâs no doubt that an operation to secure or destroy the regimeâs chemical weapons would be consistent with this countryâs stated commitment (one that all too often has not been honored) to protect civilians from the worst ravages of war.

Yes, the president must be sure before he acts; but if it is proved that Assad has crossed the âred line,â Obama must respond.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.