Calculating the cost of living

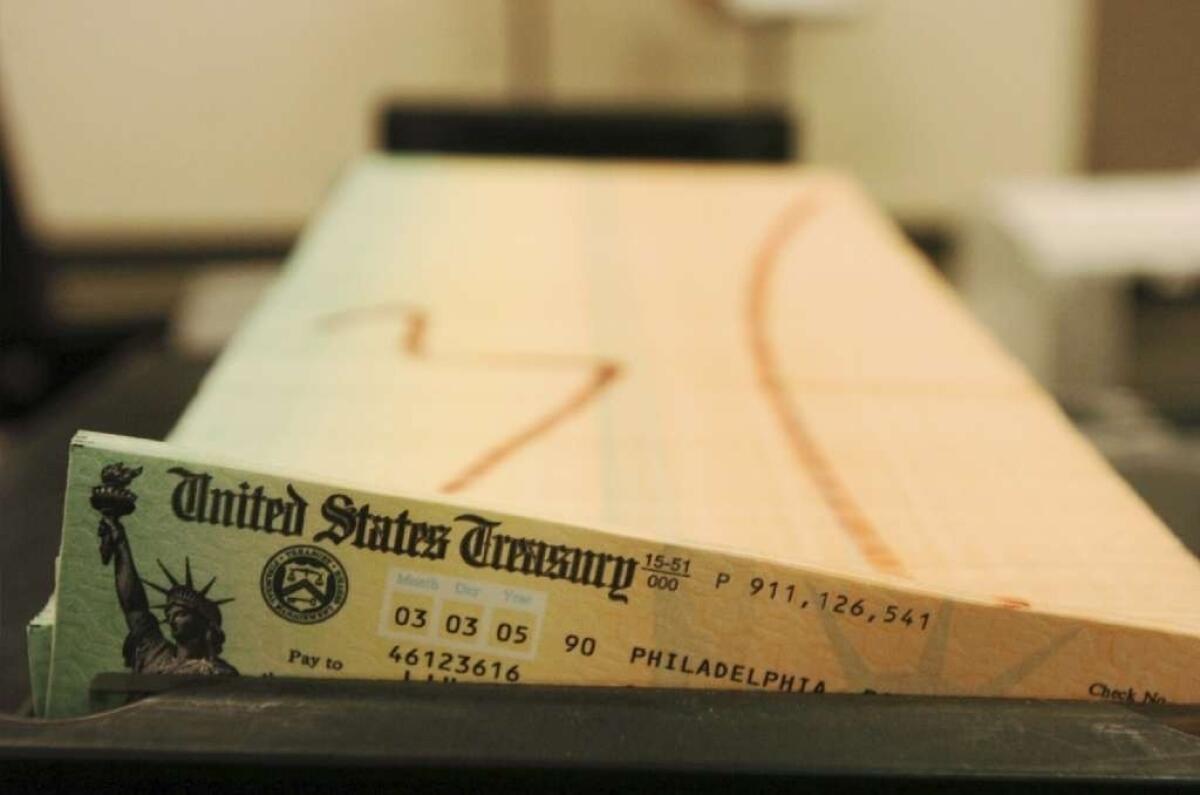

Conservatives argue that Washington never cuts programs, it just increases spending on them more slowly than planned. But to recipients of federal benefits, that type of “cut” can seem just as painful. That’s why there is an intense battle looming over a proposal to reduce the cost-of-living adjustments applied to numerous federal programs, including Social Security. The change is billed as a more accurate way to calculate the effects of inflation, but it’s really just a way to make Washington’s financial picture marginally brighter.

Both President Obama and House Speaker John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) have embraced a new version of the Consumer Price Index that’s designed to do a better job accounting for how people respond to changes in prices. The switch to “chained-CPI” would trim the annual cost-of-living adjustment slightly, reducing Social Security and other federal benefit payments by more than $100 billion over 10 years. It would also generate billions more in tax revenue by slowing the rate at which tax brackets are adjusted for inflation, causing taxpayers with growing incomes to move more rapidly into higher brackets.

Economists have grumbled for decades that the CPI overstates the real increase in the cost of living, in part because it assumes that the only way consumers react to changes in prices is to switch between more and less expensive versions of the same product. It doesn’t consider how consumers change what they put into their shopping baskets in the face of rising prices by, for example, replacing meat with pasta. The “chained” approach to CPI factors in changes in the shopping basket as well as the price of the items therein to reflect more accurately the products people are actually buying.

The problem with applying the new measure to Social Security benefits is that the surveys that are used to calculate the CPI measure the buying habits of the broad U.S. population. Social Security recipients spend a larger portion of their income on healthcare, and those costs have been rising disproportionately fast. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has an experimental version of CPI for the elderly that reflects these higher costs, but it’s based on a sample too small and generic to provide the basis for a truly accurate version of the price index for seniors.

Chained-CPI makes sense for programs whose participants are well represented by the CPI data. But if lawmakers really wanted a more precise cost-of-living adjustment for Social Security, they’d have to invest in better surveys — and accept less dramatic savings, if any. Such a change wouldn’t solve the long-term funding problems in the program, though. Nor are those problems a factor in Washington’s current deficit woes. Obama’s proposal would supposedly shelter the most vulnerable seniors and other beneficiaries from the effects of reducing their cost-of-living adjustments, and that’s a step in the right direction. But a better step would be to use chained-CPI only where it would improve accuracy, not exacerbate existing problems.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.