Brazil workers exploited as modern-day Amazon slaves

ACAILANDIA, Brazil — After months of chopping down trees in the forest without pay and living on rice, beans and dirty water, Gil Dasio Meirelles decided he had to escape from the remote clearing in the middle of the vast Brazilian Amazon.

But he would have to make his way alone through dense foliage, a place where a man can lose his bearings and find himself lost amid a constant, menacing buzz of jungle creatures.

“Three other workers helped me come up with the plan,” he said. “But they got scared and backed out. They thought that if the armed guards didn’t shoot us in the back, we’d be lost and starve in the jungle.”

He knew he had to take his chances, or die trying.

Meirelles was one of tens of thousands of Brazilians living in what critics call modern-day slavery, mostly in the Amazon jungle, where ranch owners are the law of the land.

Promised work, the victims are usually taken to remote, unfamiliar areas, where they face harsh conditions they would never have agreed to and have little chance of escape.

Some receive little or no pay. Others are told they must work to pay off “debts” for room and board. Some are threatened with violence or abused. Others simply cannot afford the journey home.

Brutal conditions and a culture of impunity across the 1.5-million-square-mile Amazon region persist in the background of Brazil’s stunning economic growth.

Although conditions and wages for most Brazilian workers have improved over the last decade, exploitation persists in the vast Amazon forest, far from the government’s reach.

In 2003, the International Labor Organization estimated that 25,000 Brazilians were working in conditions it described as slavery.

Luis Machado, head of the ILO’s unit to combat forced labor, says the number is probably larger now.

“Over 40,000 workers have been rescued since 1995,” he said. “But not one single person in the history of Brazil has been jailed for this crime. These men feel untouchable. They feel they are risking nothing by doing this.”

*

Meirelles waited until his supervisors were out of sight, then disappeared into the hot foliage.

He wandered aimlessly for hours before he got lucky and found a dirt road. As he waited hours for a car to pass, his fear slowly mixed with hunger. What if he flagged down a truck from the operation he had just fled?

He got lucky again when a “safe” truck stopped and gave him a lift to a nearby city, Acailandia, where Meirelles had heard there was a center that would help people like him.

The problem was, he wasn’t quite sure that the Carmen Bascaran Center for the Defense of Life and Human Rights of Acailandia actually existed.

Much of the work that Meirelles and others like him do reflects the illegality that reigns in the jungle. They are put to work cutting down the forest or at illegal cattle farms on protected parts of the Amazon. Others shovel illegally harvested wood into hot pits to make charcoal, often without protective gear.

The government of President Dilma Rousseff has said it is committed to fighting abuse of workers as well as illegal deforestation. Rousseff has been facing pressure from environmental and civil society groups over a new Forest Code bill that would roll back legal protections for the world’s largest rain forest.

Enforcing government rule across the Brazilian Amazon is no easy task. To find out where deforestation is occurring or illegal charcoal camps are operating, workers for nongovernmental organizations fly for hours over the jungle, circling what from a distance look like illegal activities. Then a professional navigator tries to pin down the location and later find a way to reach the site.

This kind of approach has little effect, Machado said.

“The government simply can’t be going to every farm to check. The resources don’t exist,” he said. “So we rely on trying to pressure the government to punish proven offenders and educating potential victims about the risks of taking distant jobs they know little about.”

Meirelles is rare among liberated workers in that he is comfortable telling his story in depth. He escaped in 2008 and has since had a kind of a happy ending: The Carmen Bascaran center, named for its cofounder, a Roman Catholic missionary from Spain, did exist, after all.

Eventually, he was able to bring in the police and rescue his friends and cousin, collect damages from the landowner and settle down into a new life. He speaks calmly, even proudly, about his ordeal.

But when seven men who had been rescued more recently gathered at the center this month to discuss their experiences at various charcoal plants, they spoke quickly and quietly, either timid, embarrassed or emotional.

“It was dangerous. We drank dirty water. They didn’t care for our health at all. We worked in front of blazing fire, wearing just sandals,” said Pedro Augusto Soares da Silva, 31. “I know the same owner is still using slaves right now. He’s just moved a bit.”

Antonio Perreira dos Santos, 35, said he passed out from the heat at one of the pits and was given no medical attention for three days.

“They seemed unconcerned if we died. It was only through the threat of violence against them that we got them to send a sick and dying colleague out of the camp. ‘If he dies, he won’t be the only one,’ we said, and that eventually worked.”

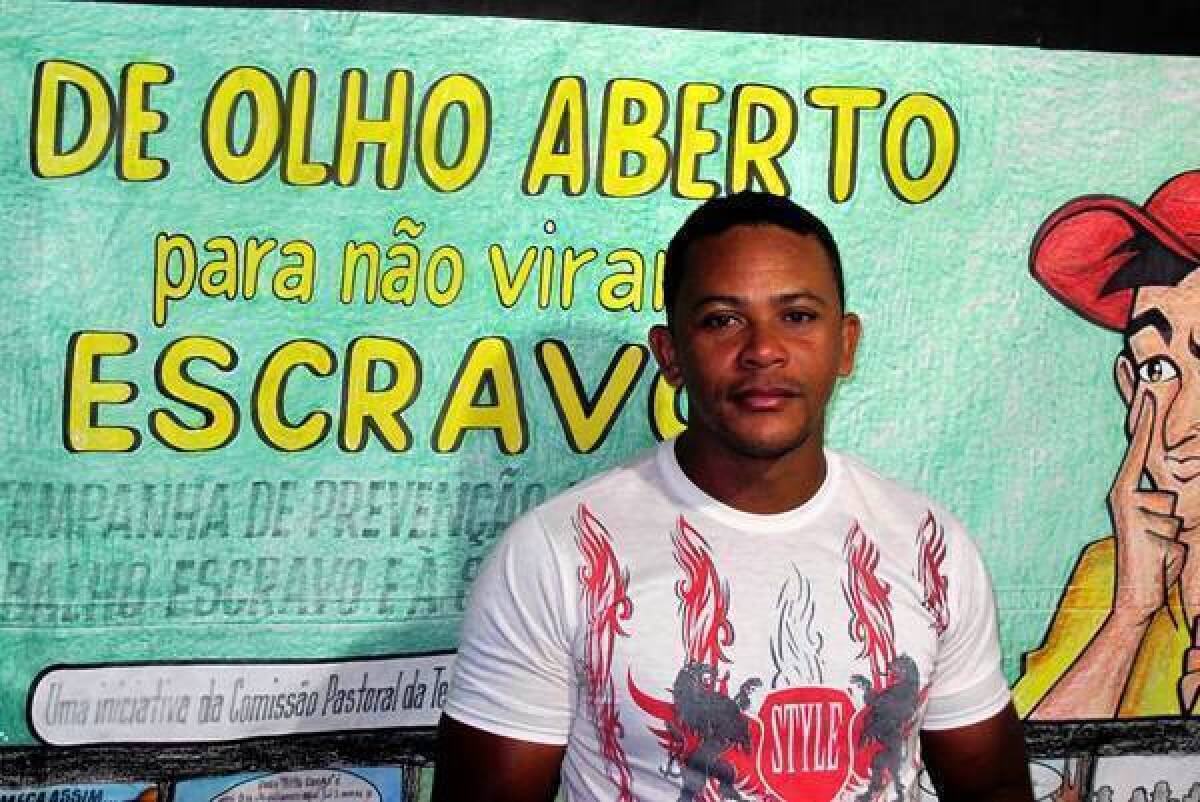

Recently, workers at the Bascaran center have been canvassing the region and distributing cartoon booklets titled, “Keep Your Eyes Open to Avoid Becoming a Slave.”

“There are about 500 cases of workers each year who manage to be rescued and file specific complaints,” said Antonio Ferreira Lima, the group’s director. “Most come to nothing. The government simply has little control over powerful landowners in this part of Brazil.”

Meirelles said it took the authorities months to finally get out to the farm where Meirelles had left his cousin and friends behind. He refused to leave the Bascaran center until they did, and slept in the back room.

“The response times are faster now, which is good,” he said. “And more people know about the risks of taking this kind of work, and thankfully, there are more jobs now here in the city so people don’t have to fling themselves into the middle of nowhere for the promise of some pay.”

Many of the liberated workers now do similar jobs but earn the official minimum wage of 600 reals, or about $300, a month, have safe working conditions and can visit home.

Meirelles has bought a small piece of land with the money he won in court and is building a house with his girlfriend.

“I think slavery is the right word to use for what we went through,” Meirelles said. “They are conditions we did not choose.”

Bevins is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.