Fort Hood tragedy rocks military as it grapples with mental health issues

The U.S. military’s culture of silence about troops’ mental health had finally begun to change.

In the early years of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the various branches had been roundly criticized for failing to adequately address post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, and other psychiatric problems. Responding to that criticism, leaders made progress in diagnosing and treating such illnesses among service members.

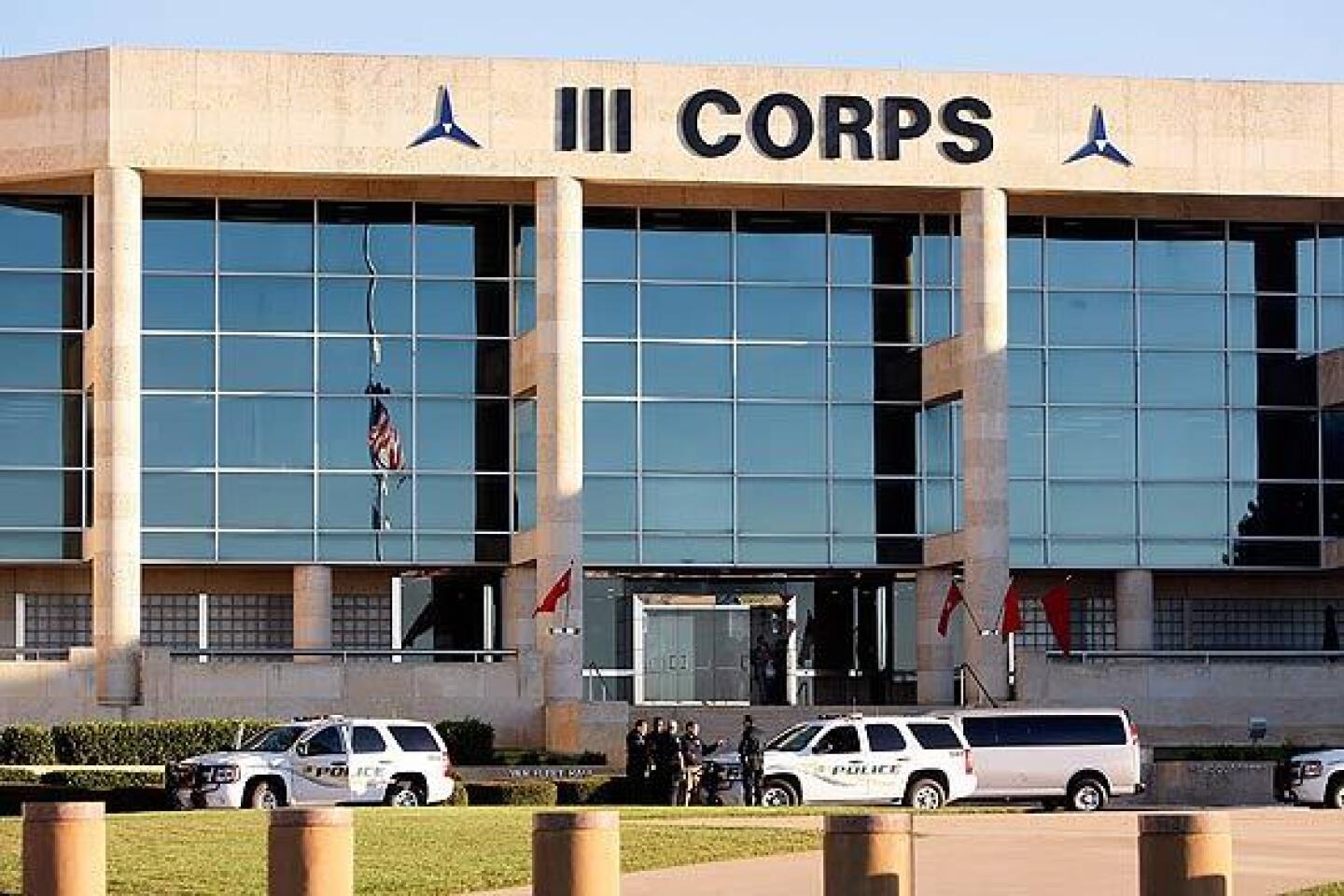

But Thursday’s attack at Ft. Hood -- as well as two other recent incidents in which military personnel allegedly turned guns on their own -- indicates an intractable problem not easily overcome.

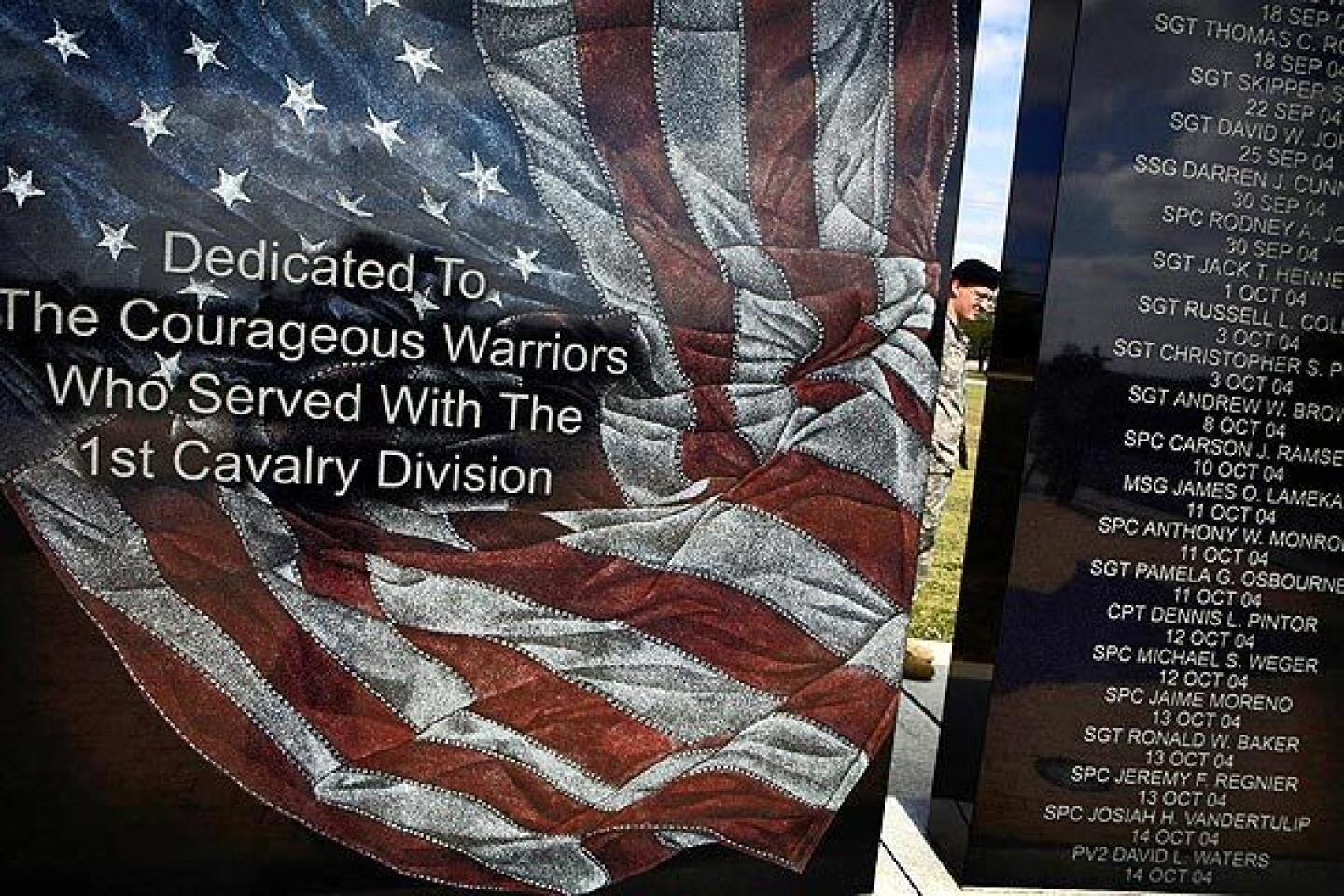

In last week’s incident, Army psychiatrist Maj. Nidal Malik Hasan allegedly fired repeatedly at colleagues on the Texas base, killing 13 and wounding more than 30, before being felled by civilian base police officers. Hasan, who was about to be deployed to Afghanistan, is now hospitalized.

The fact that the suspect is a psychiatrist “is a one-in-a-billion case,” said Floyd Meshad, who served as a psychiatric social worker in the Vietnam War and is president of the National Veterans Foundation in Los Angeles. “But it does red-flag a lot of questions.”

Those questions include whether, even today, military personnel can easily obtain mental health services.

The factors that may have led to Hasan’s alleged actions are not yet clear. What is clear is that no one is immune to mental health problems: Doctors have slightly higher suicide rates than does the general population.

“Psychiatrists can have emotional difficulties too. We are humans like everyone else,” said Dr. William Callahan, a psychiatrist in Aliso Viejo who served as a flight surgeon in the 1991 Persian Gulf War. “It’s a shocking reminder of how much we need to do to get people access and better treatment.”

Military leaders acknowledge rampant psychiatric problems in their midst. According to the Army, the suicide rate among soldiers in Iraq is five times that seen in the Persian Gulf War and 11% higher than during Vietnam. The Army reported 133 suicides in 2008, the most ever. In January of this year, the 24 suicides reported by the Army outnumbered U.S. combat-related deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Marine Corps also reported an increase in suicides in 2008, to 41. The Army and Marine Corps have provided most of the troops in the two wars.

In April 2008, researchers at the Rand Corp. published a study showing that almost 20% of personnel returning from Iraq and Afghanistan reported PTSD or depression. Just over half of those had sought treatment.

“I think the military fully understands the magnitude of this problem,” said Dahr Jamail, a journalist and author of a new book, “The Will to Resist: Soldiers Who Refuse to Fight in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

“This issue of redeploying people repeatedly is a massive crisis,” Jamail said. “It’s creating a point of collapse in the military.”

In fact, Jamail said, he is surprised that violent incidents aren’t more frequent.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have generated an array of mental and behavioral problems, experts say. Besides PTSD, a high rate of traumatic brain injury has contributed to cognitive and psychiatric symptoms. The wars have been long and, without a national draft in place, many troops have been subject to repeat deployment. The nature of the conflicts -- fighting insurgents who mingle among civilians -- is considered an additional, constant source of stress.

Military violence has been a problem in recent years. An Army sergeant has been accused of killing two superiors at a base south of Baghdad last year. And in May, an Army sergeant allegedly opened fire in a stress clinic on a base in Baghdad, killing five fellow soldiers.

The symptoms of mental health problems can include anxiety, depression, hyper-vigilance, insomnia, nightmares, emotional numbness, cognitive difficulties and intrusive thoughts. Some troops report feelings of guilt or sorrow that they cannot overcome. Others begin to abuse alcohol or drugs. Loneliness, divorce and domestic violence are common.

Service personnel have traditionally been reluctant to seek counseling because doing so might go on their records, said Meshad, who teaches mental health workers about compassion fatigue -- a gradual erosion of compassion for one’s patients and apathy about their plight.

“We have a system that has a Catch-22, and it’s time the military faced it,” he said. “These soldiers would like to see a therapist. But there must be a way where it can be confidential.”

Recently, military leaders have made strides in addressing the mental health crisis. In 2007, the Defense Department established the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury to promote prevention and treatment.

The department also recently launched a program called Real Warriors to fight the stigma surrounding mental health issues and promote treatment. In July, the Army provided $500 million for the largest study ever on suicide and mental health issues among military personnel and last month announced it would begin emotional-resilience training to prepare troops for the psychological duress of service.

“The military is doing more and more to address emotions,” Callahan said. “They are becoming more focused and precise in realizing they have got to prepare people emotionally for war.”

Some say military mental health providers, possibly including Hasan, carry heavy workloads as a result.

“They are horribly burned out,” said Aaron Glantz, author of the 2009 book “The War Comes Home: Washington’s Battle Against America’s Veterans.”

Military psychiatrists can face especially frustrating circumstances because they may recommend releasing a soldier from active duty or redeployment because of mental health problems, only to be overridden by a commanding officer, Glantz said.

In 2007, a soldier at Ft. Hood told mental health services that he was suicidal, but he was nonetheless ordered to redeploy.

“His commanding officer said, ‘I don’t care, I want you redeployed anyway,’ ” Glantz said. “He walked into a field and killed himself. Imagine if you’re the psychiatrist in that situation. All of these psychiatrists are experiencing this.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.