In FBI records, clues about a photographerâs work as an informant

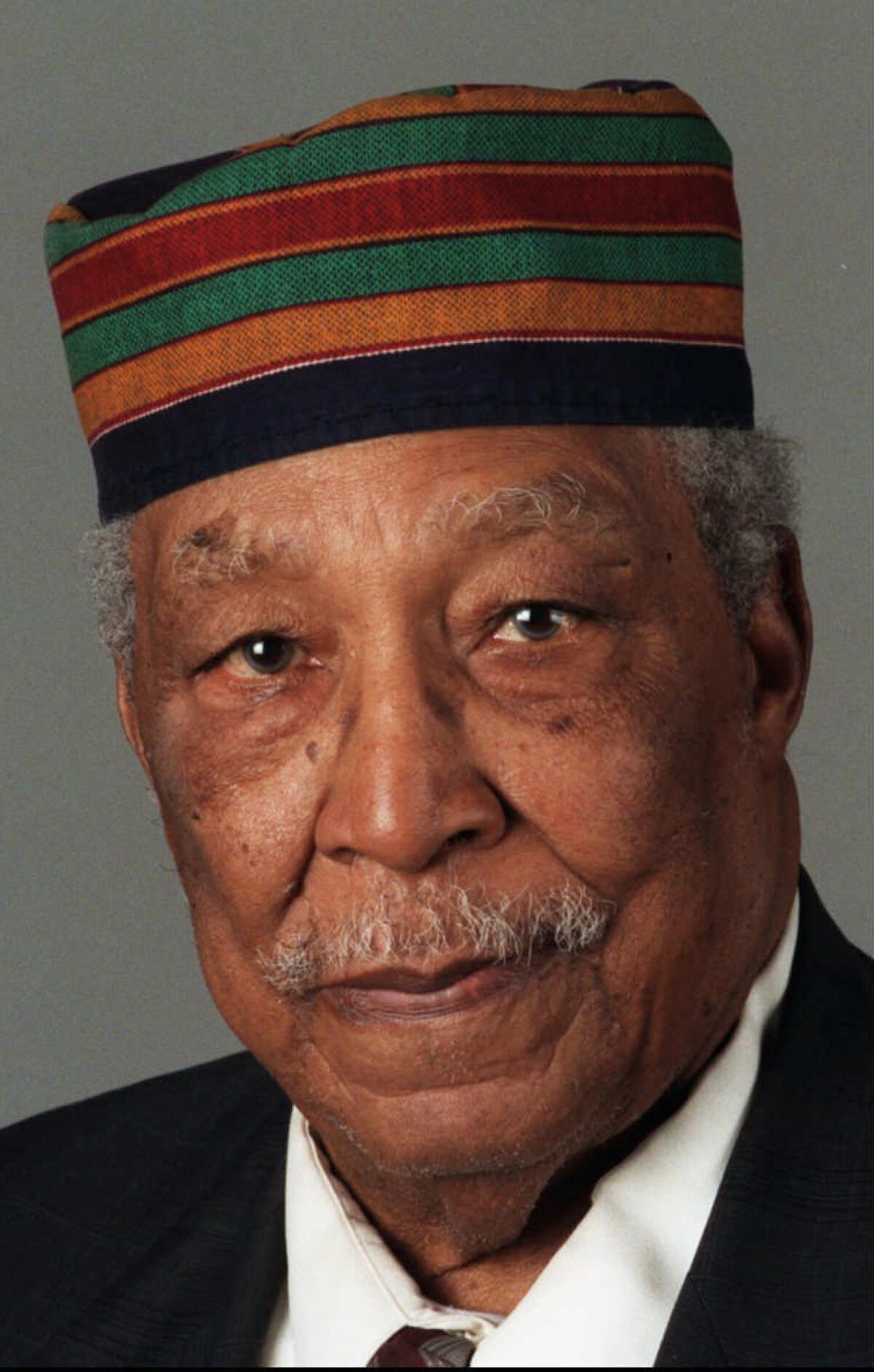

Ernest Withers watched the trajectory of the civil rights movement from behind his camera lens.

He was in Mississippi in 1955 when an all-white jury acquitted two white men accused of brutally murdering Emmett Till, a visiting black Chicago teenager, for whistling at a white woman.

He was in Alabama a year later when Martin Luther King Jr. rode a bus on the first day the Montgomery transit system was desegregated.

He was in Memphis in the spring of 1968 to support striking black sanitation workers. And he was in Kingâs Memphis hotel room on April 4 when James Earl Ray leaned out a nearby rooming house window and fired his rifle, assassinating the civil rights leader.

The renowned black photographer captured intimate, iconic moments. When he died in 2007 at age 85, his obituaries illustrated that he too was an icon.

Three years later, however, a Memphis newspaper broke a story that rocked the country: Its two-year investigation showed Withers had long worked as an informant for the FBI.

The Commercial Appeal article, which reporter Marc Perrusquia wrote using documents obtained from the FBI, revealed that between 1968 and 1970, Withers slipped the FBI tips and photographs âdetailing an insiderâs view of politics, business and everyday life in Memphisâ black community.â

Although the most of the documents were redacted, the newspaper pieced together key tidbits of information, including Withersâ confidential informant number - ME 338-R. The âR,â the article said, meant Withers had worked as a racial informant.

The article not only raised questions about Withersâ legacy, but it also provided a sneak peek into the labyrinth-like process of requesting information from the government.

Two months after the story broke in 2010, Perrusquia and the Memphis Publishing Co., the newspaperâs publisher, lodged a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit against the FBI. Although the early trove of documents had alluded to Withersâ work as an informant, Perrusquia wanted a copy of the confidential informant file.

The FBI refused. The agency wouldnât even say whether such a file existed.

In a court memorandum filed last year, the FBI wrote: âTo the extent plaintiff Perrusquia claims that the FBIâs release of Withersâ public corruption files disclosed information from which he could deduce Withersâ alleged status as a confidential informant, any such disclosure would have been inadvertent.â

U.S. District Judge Amy Berman Jackson in the District of Columbia ruled, however, that Withersâ status as a confidential informant had already been confirmed, and she ordered the FBI to turn over a more detailed reasoning for why it denied Perrusquiaâs request.

After years of back and forth, the newspaper and the FBI have reached a tentative agreement, according to an emailed statement from the plaintiffsâ attorney, Charles Tobin.

He said his clients âare pleased with the agreement we have tentatively reached with the FBI,â but he refused to go into the specifics of the settlement.

The Justice Department didnât respond to a request from The Times for comment.

ALSO:

Duke fraternity that held party mocking Asians is suspended

Autopsy begins on gunman killed in Alabama hostage rescue

New Mexico medical board clears abortion doctor of negligence

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.