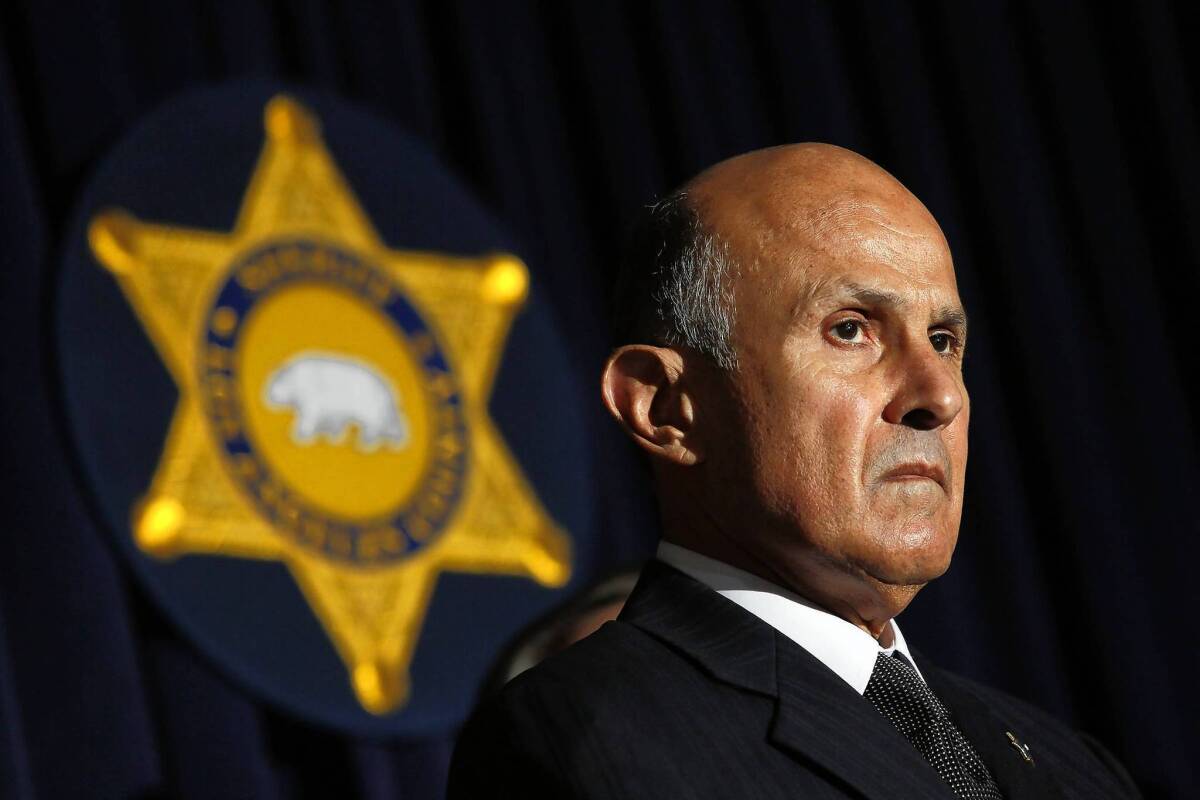

Baca played a role in handling of FBI informant, sources say

They called it Operation Pandora’s Box.

Los Angeles County sheriff’s officials learned in the summer of 2011 that the FBI had enlisted an inmate in the Men’s Central Jail to collect information on allegedly abusive and corrupt deputies.

In an unusual move, sheriff’s officials responded by moving the inmate, a convicted bank robber, to a different jail under fake names, including Robin Banks.

They assigned at least 13 deputies to watch him around the clock, according to documents reviewed by The Times. And when the operation was over, the deputies received an internal email thanking them for helping “without asking to [sic] many questions and prying into the investigation at hand.”

Whether Pandora’s Box was intended to protect the inmate or neutralize him as an FBI informant is a key issue in a federal investigation into brutality in the jails.

FULL COVERAGE: Jails under scrutiny

Four sheriff’s officials told The Times that Sheriff Lee Baca played a significant role in the operation: After learning that an inmate in his jails may have been working as an informant for the FBI, Baca called a meeting and gave his staff orders on how to handle the situation. One of the four officials said Baca continued afterward to guide the operation and get updates.

On Friday, Baca will be interviewed by federal prosecutors examining jail abuse and other problems in the Sheriff’s Department. Part of the inquiry centers on whether by holding inmate Anthony Brown under aliases and moving him, sheriff’s officials were obstructing an FBI investigation.

In an interview this week with the Times’ Editorial Board, Baca said he’s been assured he’s not a target of the investigation. Federal officials have declined to discuss details of the case. Baca’s spokesman has said Brown was moved not to hide him from the FBI but to protect him from deputies because he was “snitching” on them.

The sheriff’s officials who spoke to The Times requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media about the matter. They offered different accounts of why the department moved Brown and used aliases.

Two said the goal, at least in part, appeared to be to keep Brown and his FBI-issued cellphone from federal investigators until sheriff’s officials finished their own investigation.

But another official said the department’s only goal was protecting Brown from harm. That source said federal authorities did not return multiple calls from the Sheriff’s Department, and never asked to take custody of Brown.

Baca was vague in responding to questions about his involvement. “I’m not a hands-on person,” he said. He acknowledged being consulted about decisions regarding Brown’s “status” after they had been made. “You have to trust what your people are doing,” he said.

But he emphasized that Brown’s safety was the highest priority. “He was actually afraid of everybody, including the FBI,” Baca said.

Brown’s cover was blown after deputies discovered a phone in his cell and tracked his calls to the FBI.

Baca at the time was furious, publicly accusing federal authorities of committing a crime by smuggling a cellphone into his jail. Sheriff’s investigators were even dispatched to the home of an FBI agent involved in an attempt to interview her. Baca then reversed course and said he would cooperate fully with the inquiry.

Baca’s interview with federal prosecutors Friday marks an important moment in an investigation that has spanned more than 18 months. Federal authorities have interviewed inmates, jailers and high-ranking sheriff’s managers.

Sources familiar with the investigation say that at least two federal grand juries have taken testimony. Legal experts say that allegations of abuse, if substantiated by investigators, could result in charges against the deputies involved and possibly their direct superiors, if for example, they played a role in covering it up.

But they said building a case against Baca for abuses by his deputies would face significant obstacles.

“Just being negligent is not enough to make you responsible for other people’s actions,” said Laurie Levenson, a Loyola Law School professor and former federal prosecutor. “He has a built-in defense: ‘I didn’t know.’”

Baca has repeatedly made just that argument, saying that he was unaware of problems in his jails. A blue-ribbon panel investigating jail abuse concluded that he was an uninformed and disengaged manager.

And in the Brown case, prosecutors face a high bar if they hope to prove obstruction of justice, Levenson said. Those cases typically involve intimidation or violence against potential witnesses. In this incident, federal prosecutors would have to prove the department’s goal in moving Brown was to hinder the FBI’s investigation of the jails.

Beyond the Brown incident, federal authorities have been investigating deputies abusing inmates inside Baca’s jails — which will probably be another topic federal prosecutors ask about Friday.

The blue-ribbon panel appointed by the county Board of Supervisors blamed Baca for problems of excessive force used on inmates, saying that he did not heed repeated warnings about brutality and other problems and did not pay attention to his jails.

The sheriff has since begun implementing a sweeping set of reforms to improve oversight, accountability and jailer conduct.

Times staff writer Jack Leonard contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.