Fatal shark attacks: How rare they are and how to stay safe

- Share via

A 65-year-old woman was killed in an apparent shark attack off the coast of Maui, Hawaii, on Wednesday: According to statements by the County of Maui, Margaret C. Cruse had been snorkeling with friends and was found floating alone in the water. She had suffered fatal injuries to her upper torso, consistent with a shark attack and was brought ashore by other beachgoers. Officials closed the beach for one mile in each direction from the attack. Also on Wednesday, officials here in Seal Beach posted shark warning signs near the water after lifeguards spotted a pair of juvenile great white sharks near the surf line.

Worried about getting attacked by a shark? The L.A. Times spoke with researchers at the University of Florida, who keep the International Shark Attack File, to find out how likely that is to happen and what to do if it does:

You’re more likely to be struck by lightning than killed by a shark.

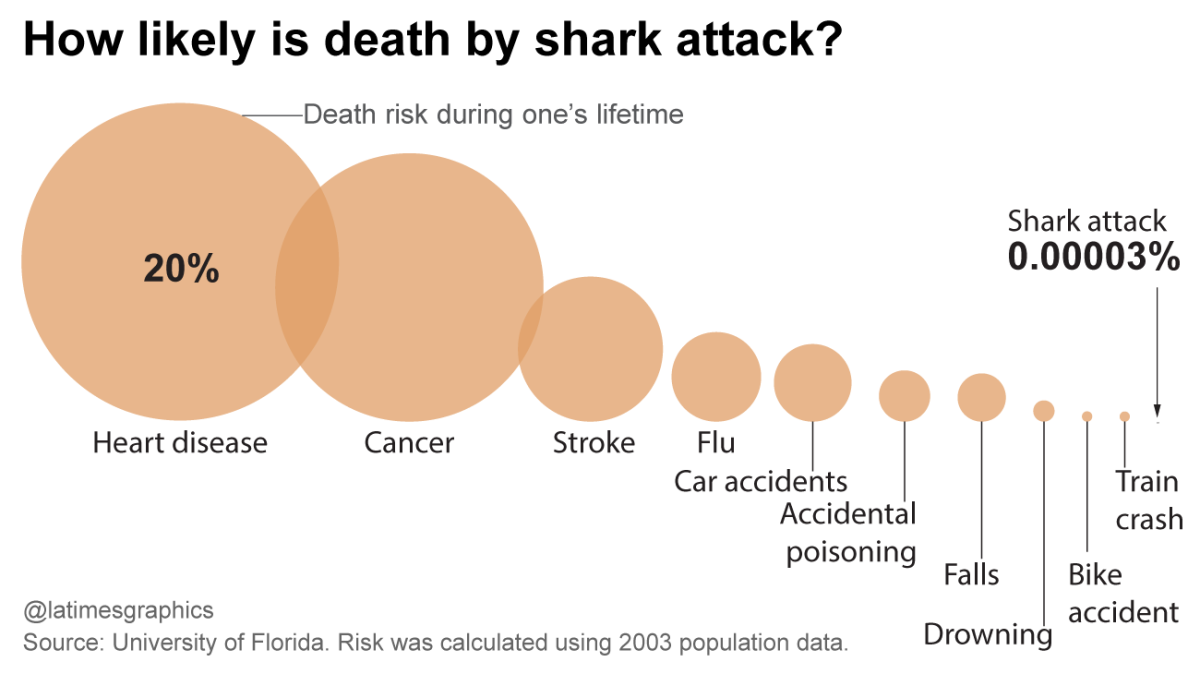

Shark attack deaths are exceedingly rare.

For Americans, the lifetime risk of dying from a shark attack is approximately 1 in 3.7 million. That means you have a greater chance of dying from heart disease (1 in 5), being killed by lightning (1 in 79,746) or experiencing death by fireworks (1 in 340,733).

Only three people died worldwide last year of shark attacks, none of them in the United States. For comparison, studies suggest humans kill an estimated 26 million to 73 million sharks for their fins every year.

Before Thursday, the last unprovoked fatal shark attack to occur in the United States was in August 2013, when a 20-year-old German woman died after a shark bit off her arm as she was snorkeling.

Later that year, a Washington man who was fishing from a kayak off the coast of Maui died after a shark bit off his leg. Because he was fishing, that attack was considered provoked.

The last fatal shark bite in California was in October 2012, when a great white about 15 feet in length attacked Francisco Javier Solorio Jr. as he was surfing off a beach in Santa Barbara County. Solorio, 39, suffered a massive torso wound and died shortly after he was brought ashore.

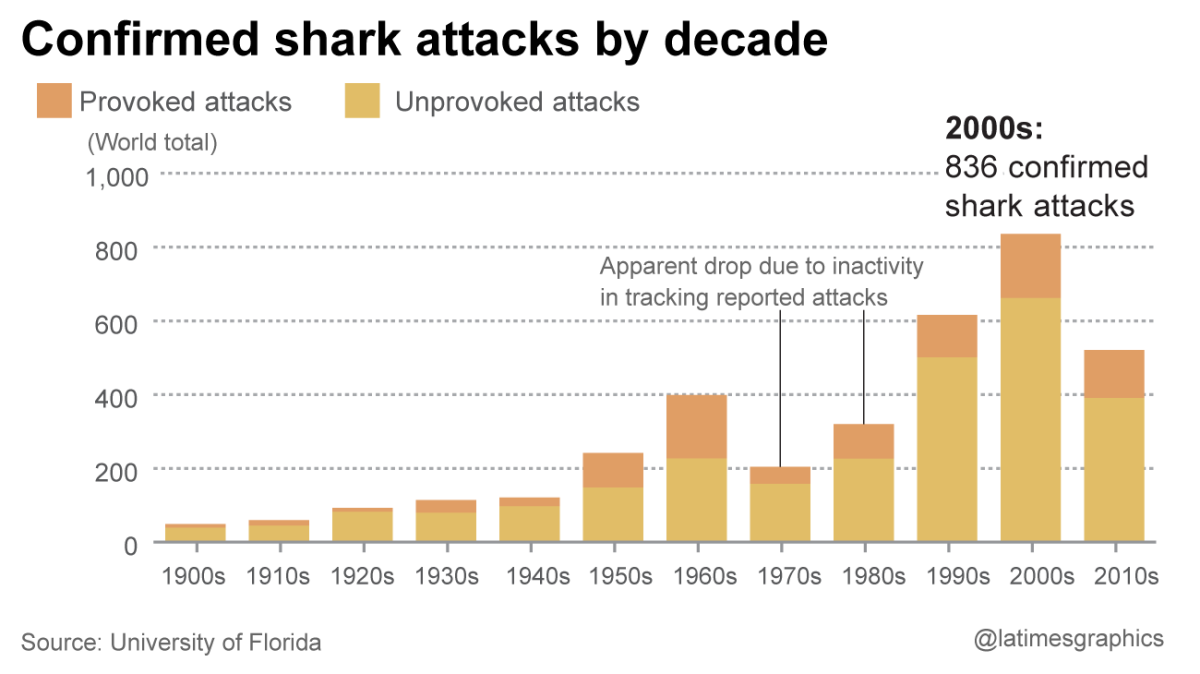

The frequency of shark attacks worldwide has risen.

Shark attacks have been steadily increasing over the last century, with nearly each decade having a higher number of attacks than the last. This is probably because humans are spending more and more time in the ocean, increasing opportunities for interactions with the animals.

"All of us enter the sea with as little clothes and protection as possible, and we're going into a wilderness area that has animals that are 20 feet long and have sharp, sharp teeth," said George H. Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research, which compiles the International Shark Attack File database. "The fact is we flood the sharks out of their own environment. We go into their territory, and now we're an instigator of these interactions by intruding into their aquatic turf."

Still, only 72 shark attacks occurred worldwide last year. When compared to the billions of hours humans spend in the water each year, experts say, that total is “remarkably low.”

The percentage of shark attacks that are fatal, meanwhile, has fallen.

Shark attacks have become less and less fatal over the last century. This is probably due to increased awareness of potentially dangerous situations and to advances in beach safety and medical treatment.

Surfers and other boarders are most likely to be bitten.

In recent decades, surfers have been most affected by shark attacks. Experts believe it has to do with the amount of time they spend out in the surf zone, which sharks frequent, and their kicking, splashing and wiping out, all activities that can attract sharks.

Surfers and people participating in other board sports accounted for 65% of shark attack cases worldwide last year. Swimmers and waders made up about a third, and snorkelers suffered just 3%.

Very few shark species are considered dangerous to humans.

According to the International Shark Attack File, only about 30 of the more than 375 known shark species have been reported to attack humans. Of those, experts say, only about a dozen are considered particularly dangerous when encountered by people, including white sharks, tiger sharks and bull sharks.

In Florida, blacktip sharks and bull sharks accounted for about 40% of attacks from 1920 to 2012, and spinner sharks caused 16%.

In California, great white sharks are the most dangerous — accounting for 97% of unprovoked attacks from 1950 to 2012.

Most of the world's shark attacks occur in North American waters.

Nearly two-thirds of shark attacks in 2014 occurred in North American waters, which have dominated the number of attacks worldwide for decades.

In 2014, 45 of the world's 72 shark attacks occurred in North American waters. That doesn't include the seven that took place in Hawaii, which is considered part of the Pacific.

The next-largest number of shark attacks for 2014 occurred in Australia, which saw 11 incidents last year.

Florida has held the title for highest number of shark attacks in the U.S. for decades.

More than half of unprovoked shark attacks in the U.S. last year occurred in Florida. The state saw 28 shark attacks in 2014, up from 23 in 2013. Experts attribute the higher rate of bites there to the state's long coastline; the large numbers of tourists and locals using the waters, especially for surfing; and the region’s rich natural aquatic habitat.

Florida is also considered one of the biggest hotspots in the world in terms of shark attacks. Other areas of shark attack activity include Australia, South Africa and Hawaii.

Men are overwhelmingly the victims of shark attacks.

From 1876 to 2013, 92% of shark attacks occurred on men.

How to avoid getting attacked by a shark:

If you see a shark, don't bother it. Nearly a quarter of shark attacks since the 1980s have been provoked, meaning a human did something that aggravated the animal, such as grabbing its tail in the water or trying to remove a hook from its mouth. "That's like kicking a dog in the corner and being surprised it bites you in the ankle," Burgess says.

Stay in groups while you're in the water, as sharks are more likely to attack a lone individual.

Don't venture too far from shore — you'd be far away from help if something happened.

Avoid going out on the water at night or in the twilight hours, when sharks are most active.

Don't go into the water if you're bleeding — sharks have an acute ability to smell blood.

Avoid waters where fishermen may be placing bait, especially chum. A good clue: diving seabirds.

Don't wear shiny jewelry, as it can reflect light and resemble the flash of fish scales in the water.

What to do if you're attacked:

If you see a shark from a distance, don't panic. Stay in one place and be as quiet as possible.

If the shark begins to approach, leave the water by swimming as quickly and as smoothly as possible, keeping an eye on the shark the whole time and keeping your group or partner close.

If the shark appears to be getting aggressive — by swimming quickly in a zigzag pattern or rushing at you — try to back up against any structure available, such as rocks, a reef or a boat.

If a shark attacks you, you should hit it on the tip of its nose. This will usually cause the shark to retreat. If it doesn't, and the shark grabs hold of you in its mouth, defend yourself aggressively by clawing at its eyes and gill areas or pounding as hard as possible. Playing dead will not work.

Exit the water as quickly as possible, as blood could encourage the shark to attack again.

For more breaking news, follow me @cmaiduc on Twitter.

UPDATES

4:47 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from George H. Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research, and with additional details.

The first version of this article was published at 2:57 p.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.