Op-Ed: The Supreme Court’s bad call on Affordable Care Act

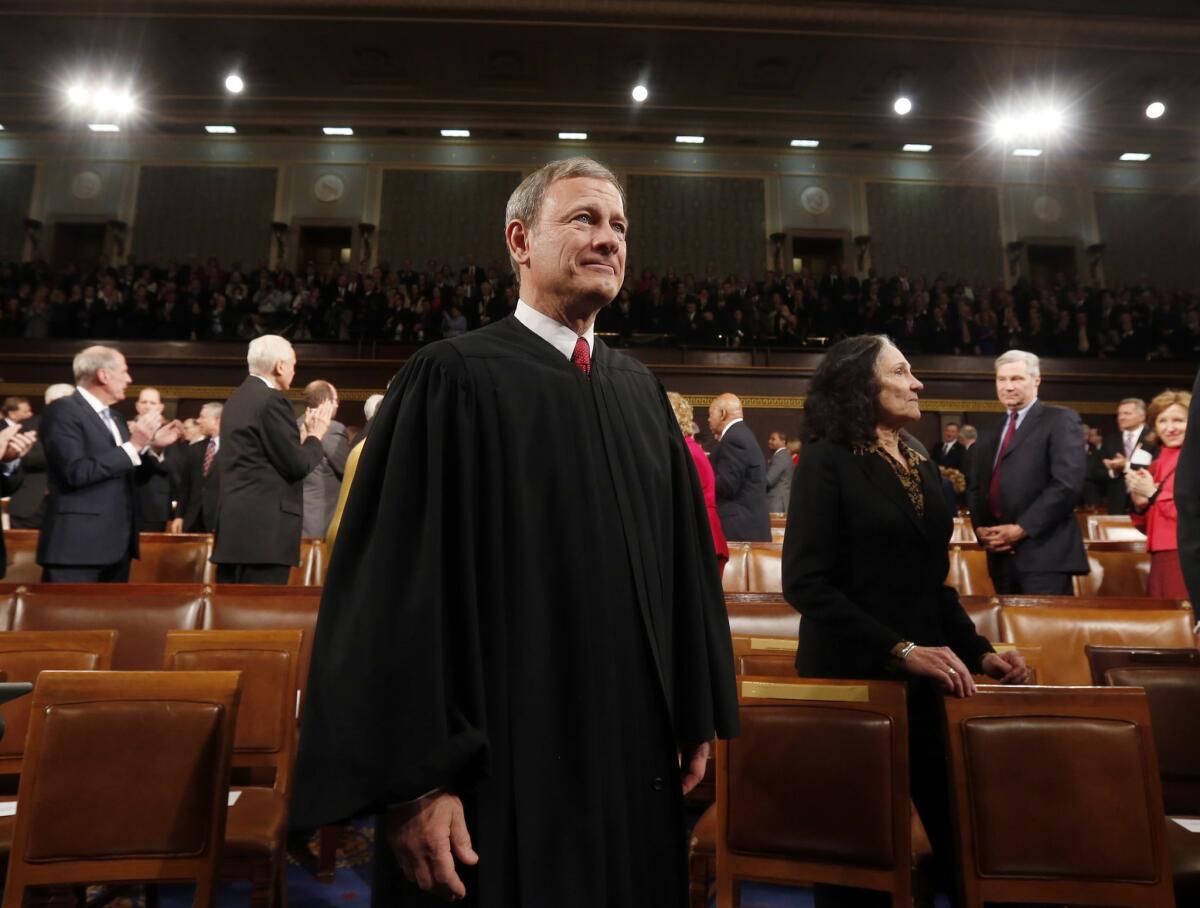

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wrote the Supreme Court’s 6-3 decision that lets the federal government keep providing health insurance subsidies even in states that haven’t set up insurance exchanges. Above, Roberts in 2014.

- Share via

In King vs. Burwell, the Supreme Court ruled that the Affordable Care Act permits individuals who purchase insurance on the federal exchange to receive taxpayer subsidies. Though the King decision pleases the ACA’s ardent supporters, it undermines the rule of law, particularly the Constitution’s separation of powers.

Under Section 1401 of the ACA, tax credits are provided to individuals who purchase qualifying health insurance in an “[e]xchange established by the State under Section 1311.” Section 1311 defines an exchange as a “governmental agency or nonprofit entity that is established by a State.”

As Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent notes, one “would think the answer would be obvious” that pursuant to this clear language, subsidies are available only through state-established exchanges.

Yet the King majority ignored what the ACA actually says, in favor of what the Obama administration believes it ought to have said, effectively rewriting the language to read “exchange established by the State or federal government.”

Scalia observes that “Words no longer have meaning if an Exchange that is not established by a State is ‘established by the State.’” Like Humpty Dumpty in Lewis Carroll’s “Through the Looking Glass,” the majority claims that when the court is asked to interpret a word, “it means just what [the court chooses] it to mean — neither more nor less.”

To reach the desired meaning, the King majority declared that “an exchange established by the State” was somehow ambiguous, enabling it to ignore the text and advance instead its vision of the ACA’s overarching purpose. But the precedent upon which the King majority relied for this contextual interpretation, FDA vs. Brown and Williamson Tobacco Corp. (2000), involved a fundamentally different situation.

In that case, a group of tobacco manufacturers challenged the Food and Drug Administration’s authority to regulate tobacco products as “medical devices” or “drugs.” The court concluded that the words “device” and “drug” did not directly address tobacco and were consequently ambiguous.

The court looked beyond the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, or FFDCA, for contextual clues, discovering that Congress had subsequently passed several statutes allowing the continued sale of tobacco products, while regulating their labeling and advertising. This suggested to the justices that Congress did not intend tobacco to be regulated under the FFDCA as a drug or device.

In King, by contrast, there were no subsequent statutes providing contextual clues about congressional intent. The only reliable evidence was contained in the act’s language itself. This extra-textual approach is deeply problematic for the rule of law, since discerning a statute’s meaning from its context is always a dicey proposition, necessitating judicial inquiry into inchoate matters such as the law’s “purpose.”

Ascertaining a law’s purpose from evidence outside its text is virtually impossible, given that Congress consists of 535 members, each of whom is motivated by different purposes. This is why, at least until King, the court has not resorted to contextual interpretation when the text is plain.

In the words of Palmer vs. Massachusetts (1939), contextual interpretation is a “subtle business, calling for great wariness lest what professes to be … attempted interpretation of legislation becomes legislation itself.” Yet this is exactly what happened in King: Attempted interpretation became legislation itself. By ignoring what the ACA actually says, in favor of what the King majority believes the statute ought to have said or what it thinks Congress meant to say, the court upset the entire constitutional balance.

The King majority acknowledged that the ACA is full of “inartful drafting” and was written “behind closed doors, rather than through the traditional legislative process.” It also conceded that it was passed using unusual parliamentary procedures, and “[a]s a result, the Act does not reflect the type of care and deliberation that one might expect of such significant legislation.”

Despite all these flaws, the majority felt compelled to save Congress, and the ACA, from its own foibles. Specifically, the King majority believed that applying the ACA’s plain meaning “would destabilize the individual insurance market in any State with a Federal Exchange, and likely create the very ‘death spirals’ that Congress designed the Act to avoid.”

Even if a loss of subsidies would have exacerbated the death spiral, courts are emphatically not in the law-writing business. Article I, Section 1 of the Constitution grants “all” lawmaking power to Congress,” not merely “some.” The job of the judiciary is to implement laws, warts and all.

When judges take it upon themselves to “fix” a law — or to bless an executive “fix” — they diminish political accountability by encouraging Congress to be sloppy. And they bypass the political process established by the Constitution’s separation of powers, arrogating to itself — and the executive — the power to amend legislation.

This leads to bad laws, bad policy outcomes and fosters the cynical belief that “law is politics.”

David B. Rivkin Jr. is a constitutional litigator at BakerHostetler who served in the Justice Department and the White House Counsel’s Office in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations. Elizabeth Price Foley is Of Counsel at BakerHostetler and a professor of constitutional law at Florida International University College of Law.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.