How Utah quietly made plans to ship coal through California

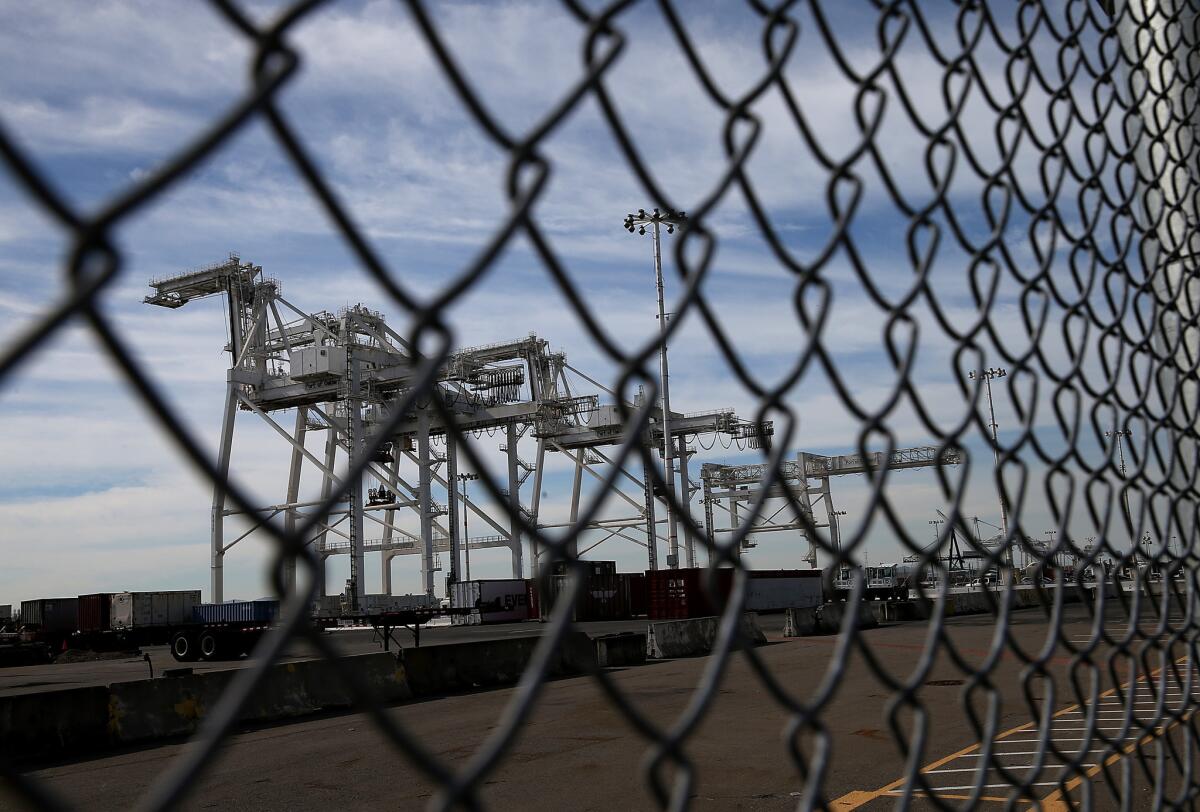

A proposed export facility near the Port of Oakland faces sharp new questions over whether it would process coal bound for Asia.

- Share via

Reporting from Salt Lake City — The troubled U.S. coal industry has said for years that its future is in Asia. The question has been how to get there.

New coal export facilities proposed for the West Coast have met stiff and sometimes fatal resistance. City councils have passed defiant resolutions saying coal terminals would increase local pollution and global greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental groups have filed lawsuits. Native American tribes have invoked historical treaty rights.

So when state and county officials in southern Utah came up with an unusual plan to invest $53 million in public money to help build an export terminal in San Francisco Bay, they decided to tell as few people as possible what commodity they planned to export.

“The script,” according to Jeffrey Holt, the chairman of the Utah Transportation Commission and a central figure in arranging the $53-million loan, writing in an email last spring, “was to downplay coal.”

Now, more than six months after Holt sent his email, the state loan has yet to be finalized and the proposed terminal — which is being developed on city property in Oakland with the help of a longtime friend and investment partner of California Gov. Jerry Brown — faces sharp new questions. Instead of stealthily helping shepherd the project, Holt appears to have inadvertently stoked opposition to it after his email was released as part of a public records request.

“All he did was make people aware,” said Margaret Gordon, a longtime environmental activist in Oakland and a former port commissioner. “That means the community organizing is happening on both ends — in Utah and in Oakland.”

And that has meant new scrutiny for what opponents say would be the largest coal export facility in California — a project that could create conflicts with California’s ambitious climate goals even as Brown has just returned from France, where he participated in the United Nations summit to address climate change.

The debate over the terminal proposal provides an unusual window into the politics of energy development in states such as Utah, whose political leaders are often as committed to resource extraction as those in the private sector; and California, where a governor staking his legacy on climate change faces an industry proposal — backed by a longtime associate — that could add significantly to greenhouse gas emissions.

The push for the proposed terminal in Oakland has been led by Phillip Tagami, a prominent developer and himself a former Oakland port commissioner. He was appointed to that role by Brown, then the mayor of Oakland.

Tagami has donated generously to Brown’s campaigns over the years, and Brown has substantial financial stakes in real estate projects led by Tagami, according to a report last year by the Bay Area News Group. Brown spokesman Gareth Lacy has said the governor “does not have a financial interest” in the proposed export terminal.

Tagami’s lawyer said the Oakland developer has no business relationship with Holt, a former executive of Goldman Sachs in the Bay Area who invests in large port and infrastructure projects. A top executive in Tagami’s company traveled to Utah in April to meet with Holt and officials who agreed to make the loan, according to public records.

A key point of controversy from the beginning has been whether the terminal was intended to process coal bound for Asia.

Proponents have said the facility could end up exporting alfalfa, potash and other less controversial commodities.

But the likelihood that coal could be part of the plan became clear this year, when four coal-producing counties in Utah moved to invest $53 million in the terminal.

The move came through the Utah Permanent Community Impact Fund Board, which makes low-interest loans using royalty money from federal mining leases. The loans traditionally have been given for public projects such as senior centers or sewer lines that would help communities affected by mining. But recently, the board, known as the CIB, has funded infrastructure projects intended to expand production of fossil fuels.

Holt, a former member of the board, has been behind at least two of the projects — the terminal and a related rail line. Both would benefit Holt and his employer, the Bank of Montreal, according to public records released in response to a request from the Sierra Club and other groups.

Emails contained in the records suggest that Holt, who has publicly downplayed any plans to export coal, had indeed discussed moving Utah coal through the Oakland facility.

“The key concept is — This is a bulk terminal, many commodities can and will go through the terminal,” he wrote in April in his suggested talking points for county leaders in Utah. “(Could coal be one of them, you ask? Sure, I guess so, but we have so many products here in the State of Utah that need rail.) Less press is best. Controlled message is critical.”

That month, Holt sought to persuade the CIB to loan money to the four counties in south-central Utah so they could invest in the Oakland terminal.

Holt has advocated for both the rail and the terminal at the highest levels of state government and has sought to smooth over potential questions.

At its vote in April, the CIB said it would ask Utah Atty. Gen. Sean Reyes to assess the legality of using CIB funds for the Oakland project.

Holt texted Utah Lt. Gov. Spencer Cox in late October, saying he and others were planning to meet with Reyes’ staff and asking whether Cox or Utah Gov. Gary R. Herbert “could come by and give some words of encouragement to the parties assembled.”

“The plan,” Holt texted, “is to turn the [attorney general] folks into road map not a road block on these large infra projects.”

The following week, after the Sierra Club, Earthjustice and other groups wrote to Reyes alleging that the planned loan violated several laws, Holt wrote to Justin Harding, Herbert’s chief of staff. “Official State support would be timely,” he wrote.

Harding replied that the governor’s office had “intimated state support for this project on a number of occasions and in a number of ways” and “will determine appropriate ways to reach out and affirm our position.”

Jon Cox, a spokesman for Herbert, said in an email to The Times that the governor “is supportive of the concept of this project, but he is awaiting final legal review from the Utah Attorney General’s office.”

Holt declined to respond to repeated Times requests for comment by phone and email.

On Friday, he announced his resignation as head of the Utah Transportation Commission, citing his

family’s recent move to New York for his private sector job.

In Oakland, port officials rejected a different proposed coal terminal last year. The Tagami project, however, would be on city land, not property controlled by the port.

Mayor Libby Schaaf, however, has been a vocal opponent of coal development, and this year she had a public dust-up with Tagami after news emerged that the terminal could export coal.

At the Paris climate summit last week, Schaaf and Brown spoke at a public forum on efforts to fight global warming. Schaaf said she was “concerned about the health impacts when coal travels through or is handled in your city.”

Brown suggested that any attempts to cut back U.S. coal use would be fruitless if the coal were simply shipped overseas.

“It doesn’t make sense to be shutting down coal plants and then export it for somebody else to burn it in a more dirty way,” the governor said. “But what we need is a national plan to reduce all fossil fuels. Certainly, coal would be at the top.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.