Amid racial tension, ‘I love Ferguson’ shop emphasizes community

- Share via

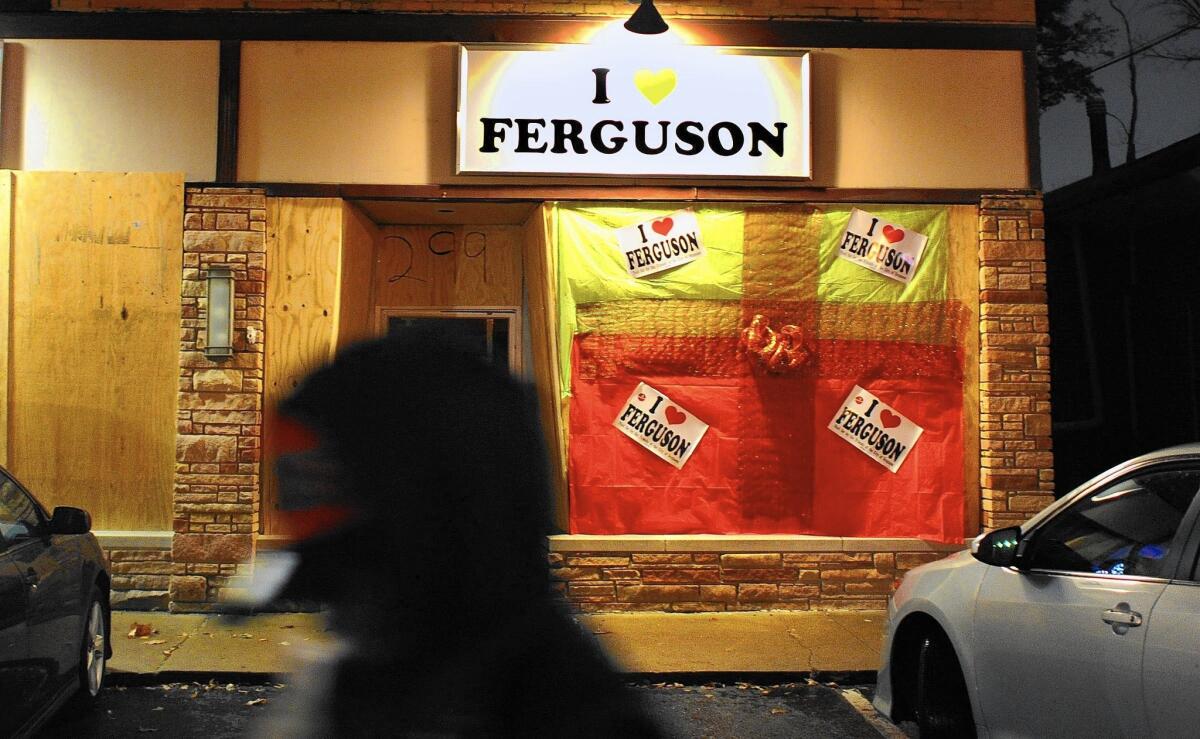

The “I ♥ Ferguson” shop is the physical embodiment of a place making the best of bad circumstances. Its entire exterior is boarded up, forming a sort of plywood box.

But its volunteer workers have covered it to look like a giant Christmas package.

It says: We are braced for riots. But we don’t like it.

Inside, there’s a touch of unreality. Along the walls, Christmas mugs and postcards and T-shirts have all been sorted and hung.

In the center of the room, a black man and white man argue.

The black man, a volunteer named Ken Wheat, shakes his head. “I’m not buying that,” he says.

He’s looking at the new Christmas sweater designs. They are red and green, with cross-stitched poinsettias along the top. In the middle: “I Love Ferguson.” Along the bottom, cross-stitched reindeer. Wheat means what he says: I’m not buying that.

His boss, former Ferguson Mayor Brian Fletcher, sits back. “They are ‘ugly sweaters,’” he says with emphasis. “They are supposed to be ugly.”

Wheat considers. He finds a middle ground: “Maybe for somebody’s mother-in-law.”

Fletcher breaks into laughter. And then picks the sweater design Wheat had preferred all along.

That’s how Wheat handles conflict. At one point an elderly woman comes into the store and chats about “what the Negroes are doing.” Wheat smiles, and shrugs: She is an old woman. She is trapped in an old vocabulary. But like Wheat, she also ♥’s Ferguson. That’s enough for him. They’re neighbors.

After a few minutes of conversation with Wheat, anyone might wonder if the local, state and federal agencies descending on Ferguson should hand over authority to him, a 47-year-old banquet captain at a downtown hotel. He has no badge. He does have a stutter. But he sees conflict — particularly race — with clarity.

“My parents were born in the ‘20s, and my father was from Arkansas, where he had struggles with race. My mother was the kindest, calmest person when it came to race,” he says. “I find a balance between them.”

When the protests first started in August, after a white Ferguson police officer shot and killed a young black man, Wheat identified with the protesters. They felt mistreated, and wanted justice.

Then, he said, he watched as local people were supplanted by agitators from out of town. Unfamiliar people. Angry people.

His heart broke, he said, when he saw storefronts smashed and public officials vilified. “These are my friends,” he said. “So I had to make this shift from calling for justice to protecting my town.”

Wheat lives in downtown Ferguson, just around the corner from the shop that locals set up to show their devotion to this St. Louis suburb. His wife, Stephannie, answers the door with a smile and an emphatic “Surprise!”

She is white.

The two met 15 years ago, she says, and they married three months later. Their adopted son, Christopher, is black. “We have not felt any problems here because when we moved here Ferguson was 50-50,” she says. Half black, half white.

So where did the anger come from? The public rage, in the aftermath of the shooting?

Her hands fall to her sides and her head drops, as though she is suddenly exhausted. “That’s the thing,” she says. “We just can’t figure it out.”

Christopher, 10, nods as his mother talks. From time to time, he says, kids at school will ask, “Hey, why is your mom white?”

“So I just ask them, ‘Why is your mom black? Our moms are just our moms.’”

Stephannie laughs and stares at him. “I didn’t know anyone asked you that,” she says.

“Yeah.”

“Well that’s a good answer, kiddo. That’s good.”

Christopher smiles and leaps away, already moving on to something else in his world. He has his father’s ease in the midst of conflict. Balance. Unexpected laughter.

Stephannie watches him, and when he’s gone she turns back and says to no one in particular, “That’s good.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.