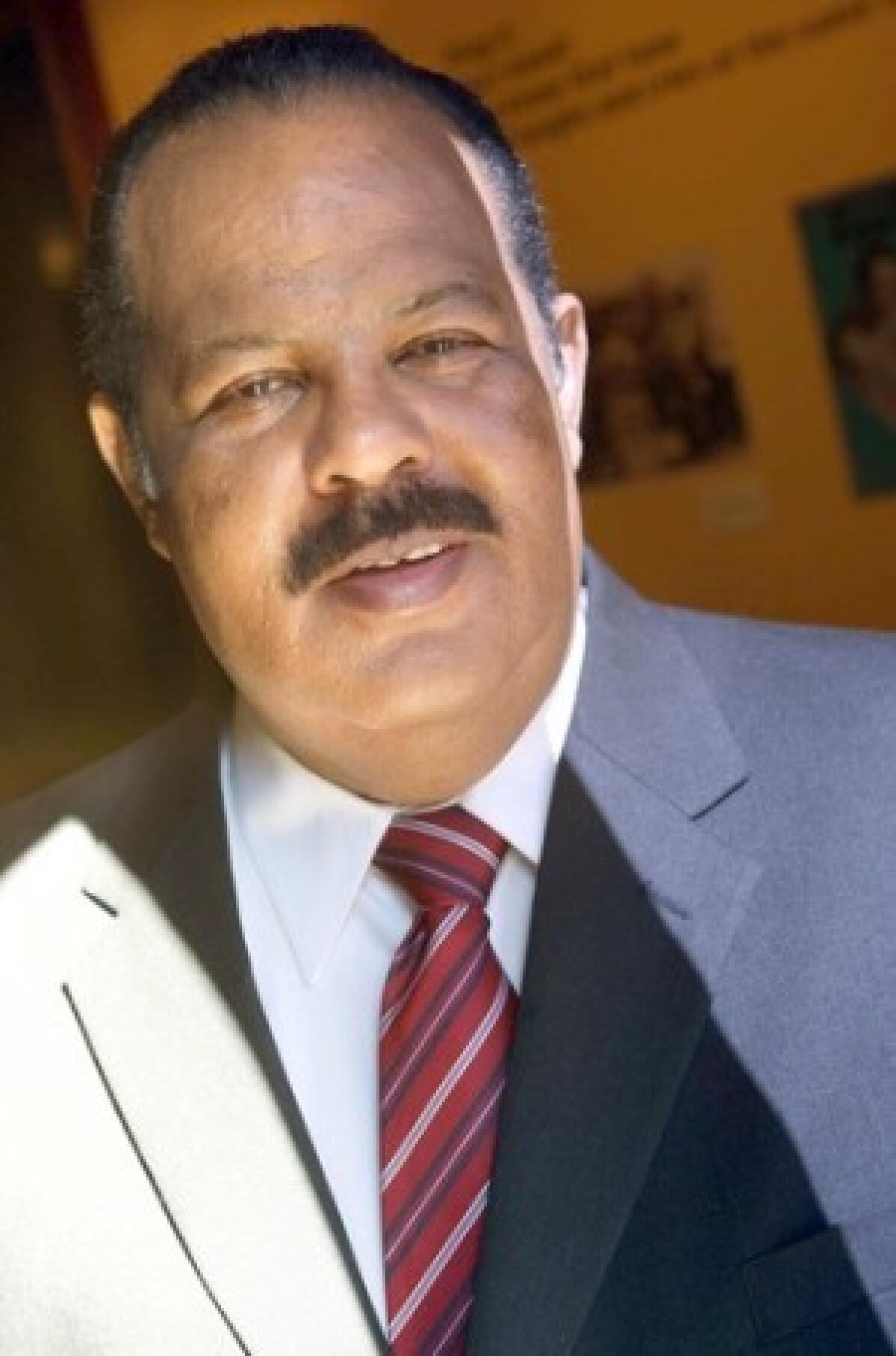

Avery Clayton dies at 62; carried on mother’s work through African American library-museum

- Share via

Avery Clayton, who carried on the work of his mother, Mayme Clayton, by establishing a library and museum in Culver City for her major collection of African American artifacts, died Thanksgiving Day. He was 62.

Clayton, a retired art teacher, died suddenly of unknown causes while hosting a holiday gathering at his Culver City home, said Evelyn Davis, a family spokeswoman.

The collection assembled by his mother -- a college librarian who haunted garage sales and then often packed her finds into the garage behind her humble West Adams home -- is a treasure trove of rare books, manuscripts, photographs, feature films and other ephemera.

Several scholars have called the collection one of the most important of its kind in the country. One jewel is a signed copy of the first book published by an African American, ex-slave Phillis Wheatley, in 1773.

Days before his mother died in 2006 at 83, Clayton signed a $1-a-year lease on a former courthouse in Culver City, intended as the first site of the Mayme A. Clayton Library and Museum.

“Her part was to assemble the collection,” Clayton often said. “I really believe my part is to bring it to the world.”

Over the last three years, he dedicated himself to raising the funds needed to open the library-museum to the public, possibly in 2010 or 2011.

Clayton also was hands on as he helped archive of “one of the largest collections of African Americana,” said Sue Hodson, director of literary manuscripts at the Huntington Library in San Marino.

About a fifth of the Clayton holdings has been archived, said Leah M. Kerr, director of archives at the library-museum.

“It’s everyone’s hope that we will be able to continue the work,” she said.

Just to move the 680 boxes shoehorned into his mother’s dilapidated garage, Clayton had to raise at least $40,000 and hire a moving company that specialized in archival collections.

Since his mother acquired the pieces of black history mainly while he was growing up, many were new to him, and he “was really having a great time of discovery,” Hodson said.

With Clayton, she co-curated “Central Avenue and Beyond: The Harlem Renaissance in Los Angeles,” the first major exhibition to pull from his mother’s collection. It opened last month at the Huntington and will remain on display through Feb. 8.

The Clayton collection is strong in Civil War-era books and documents, and in writers of the Harlem Renaissance. Earlier this year, Clayton opened a box and found the first book of Negro spirituals in the U.S., from 1867. Clayton particularly valued the 19th century documents written by slaves and former slaves.

“Most African American history is hidden,” he told The Times in 2007. “What’s exciting about this is that we’re going to bring it back and show that black culture is rich and varied.”

Born in Los Angeles on March 17, 1947, Clayton was the eldest of three sons of Mayme Agnew Clayton and Andrew Clayton, who owned a barbershop.

His mother was the daughter of the only black merchant in Van Buren, Ark., and she grew up with an awareness of black achievements. For four decades, she prowled secondhand venues as she “saved our history,” Clayton recently recalled.

As a child, he didn’t pay much attention to his mother’s hobby. When she would interrupt her sons’ cartoon-watching to excitedly chatter about buying a book by Booker T. Washington, “we would say, ‘That’s nice’ and go back to watching TV,” he said in a recent Times interview.

As a teen, he realized “that what my mom was doing was important,” and as he got older, he said that he knew he would “take up the mantle one day.”

Clayton served in the Army during the Vietnam War. Upon returning home in 1967, he studied at Los Angeles City College and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in art from UCLA.

In the mid-1980s, he started teaching art in public schools and also was a guidance counselor. He also painted, produced pen-and-ink drawings and distributed his own greeting cards.

That same decade, Clayton entered a rough period in his life that intensified when his father died in 1987. He temporarily lost his desire to paint.

After discovering he had congenital kidney problems, Clayton had a kidney transplant in 1999.

The result left him feeling “completely new,” he recently recalled. It also led him to reconsider what he was doing with his life and, in 2002, he decided to devote himself to his mother’s collection.

“He had such a dream and a vision and a passion for what he was doing,” Hodson said.

“He wanted something that would reach out to everyone,” she said. “He especially wanted black children to see evidence of important historic events that they might not learn about in school but that were an important part of their heritage.”

Clayton is survived by his brothers, Renai and Lloyd.

Freelance writer Karen Wada contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.