Court rejects key lawsuit against California high-speed rail system

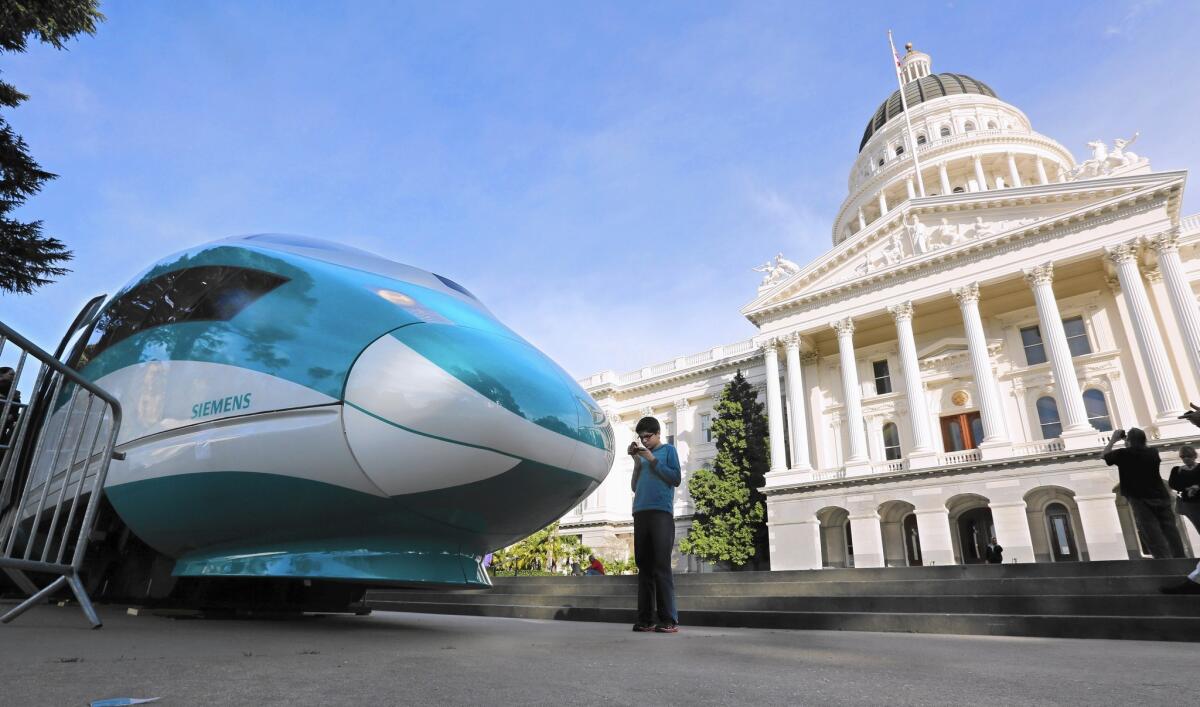

The California bullet train has won a court victory in a key lawsuit that sought to stop the $64-billion project because it allegedly violated restrictions voters imposed in 2008.

A Sacramento County Superior Court judge ruled that the allegations in the suit were ânot ripe for review,â finding that opponents of the project offered no evidence that the state rail authority would not comply at some point with the restrictions as it continues to plan the project.

âThere are still too many unknown variables,â Judge Michael Kenny wrote in his 19-page ruling in the lawsuit brought by Kings County and two farmers. The ruling appeared to leave open the door for the lawsuit to resume in the future.

The chairman of the California High Speed Rail Authority, Dan Richard, took the ruling as a validation of the stateâs planning.

âTodayâs ruling confirms that we are indeed delivering a fast, modern and environmentally friendly high-speed rail system that meets the voter-approved requirements under Proposition 1a,â Richard said.

âThis five-year lawsuit wasted taxpayer dollars and delayed implementation, but we are moving forward and redoubling our efforts to build this transformative, job-creating investment in Californiaâs future,â he said.

Though the decision is a victory for the state, it holds the rail agency to strict compliance with some of the bond act requirements that will be difficult to meet.

Stuart Flashman, an attorney representing plaintiffs John Tos, Aaron Fukuda and Kings County, said he would have to consider his next steps and wouldnât rule out an appeal.

âThough the high-speed rail authority may have won this round, the ruling ⦠provides ominous signs about the authorityâs future use of bond funds,â Flashman wrote in an email. âIt should perhaps be considered a second shot across the bow of the authorityâs current proposed system.â

The 2008 bond act, which provided $9 billion for the high-speed rail program, required that the train system would have to be financially viable, allow the operation of trains every five minutes in each direction, operate without a subsidy, have all the funds identified for an operating segment before the start of construction and travel between Los Angeles and San Francisco in two hours and 40 minutes, among other things.

The rail project has survived a number of legal challenges, political attacks and regulatory minefields over the last several years. It is struggling to find enough money to complete a partial operating segment by 2025.

Opposition has been strong in the Central Valley, where agricultural interests are backing a proposition for the November ballot that would reallocate bonds for the rail system to new water projects.

The rail system also has encountered difficult technical problems in its plans to cross the Southern California mountain ranges and surprisingly strong resistance in working-class Latino neighborhoods along a planned route in the San Fernando Valley.

Kenny flatly rejected some of the plaintiffsâ arguments, including that the state must adhere to the bond act requirements even if it hasnât yet tapped into the bond funds for construction. His ruling leaves the state free to continue with existing work using greenhouse gas fees and federal grants, even though it will eventually need the bond funds.

So far, the state has not attempted to sell the rail bonds to fund actual construction, though some environmental planning and administrative costs have been paid for with bond sales.

In an earlier phase of the lawsuit, an appeals court reversed Kennyâs finding that the state violated the bond act because it drafted a funding plan that did not comply with the bond act. In the current ruling, Kenny defers to that decision, saying the state has so far not submitted a funding plan to use the bond dollars.

The plaintiffs in the case asserted that the rail agency violated the bond act when it reached a political compromise in 2012 to share slower speed tracks in the Bay Area with commuter and freight trains.

Instead of speeds up to 220 mph, the trains would be limited to 110 mph. Instead of four tracks through the Bay Area peninsula, the system would use two existing tracks that all the trains share. Kenny ruled that the compromise by itself was not a direct violation of Proposition 1a.

But the suit also alleged that the slower speeds and sharing of track would not allow the system to meet two key requirements: the operation of 12 trains per hour and a 30-minute trip time between San Franciscoâs Transbay Terminal and San Jose.

Kenny noted that the authorityâs own analysis showed that at 110 mph, trains would require 32 minutes to make the San Francisco to San Jose trip.

Kenny did send a strong message to the rail authority on the issue, when he said it was âmost troublingâ that the authority based its trip times on a station in San Francisco at 4th and King streets, instead of the Transbay Terminal that was identified as the end point in the bond act. Transbay is 1.3 miles farther along, accessed through a tunnel that potentially could add another minute to the trip time.

Kenny issued his ruling Friday, but it was not posted on the Superior Court website until Tuesday morning.

ALSO

Mudslide likely triggered Bay Area commuter train derailment, railroad official says

Six injured in multicar crash in Van Nuys

New Gold Line extension reopens for Monday commute after big-rig crash

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.