LAUSD college prep rule puts nearly 75% of 10th graders’ diplomas at risk

- Share via

As many as three-quarters of Los Angeles 10th-graders are at risk of being denied diplomas by graduation because they are not on track to meet rigorous new college prep class requirements.

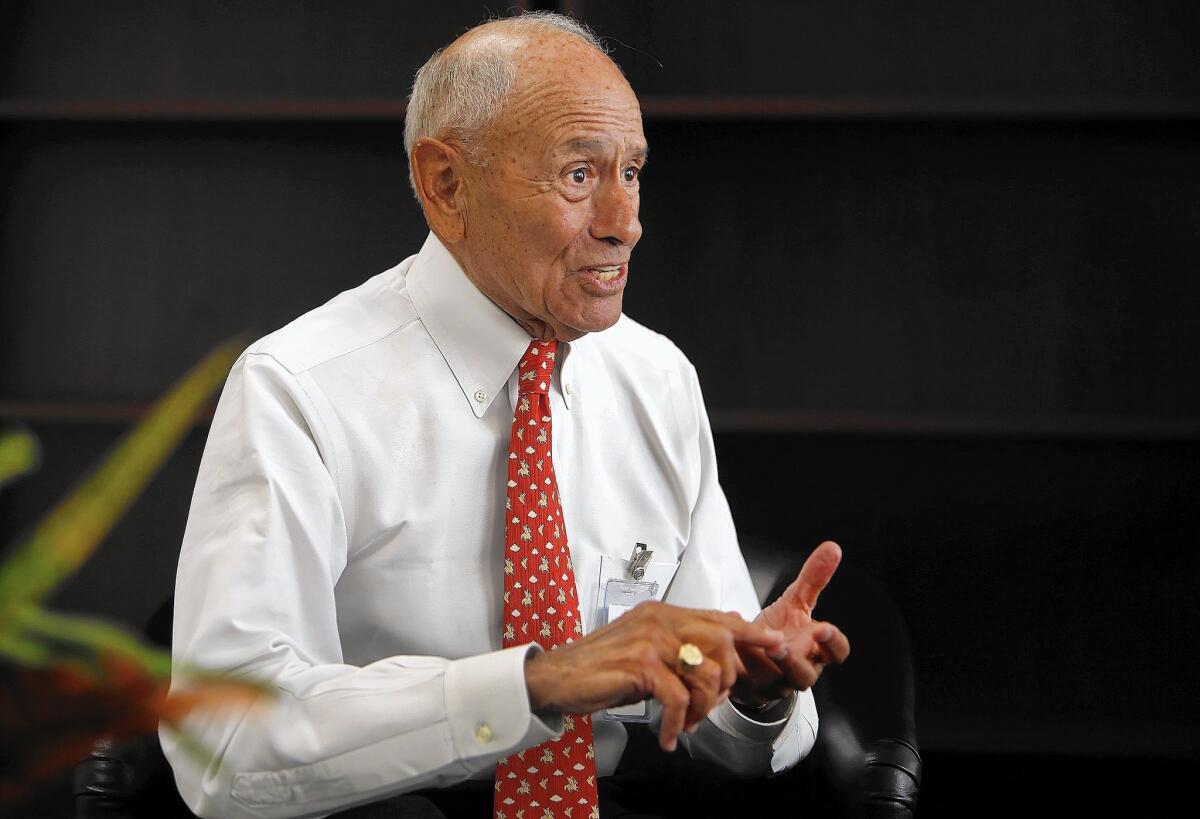

This has prompted some in the L.A. Unified School District, including Supt. Ramon C. Cortines, to suggest reconsidering the requirements, which were approved a decade ago to better prepare students for college. The plan came after years of complaints that the nation’s second-largest school system was failing to help underprivileged students become eligible for and succeed in college.

In an interview, Cortines said the effort is laudable, but that it would be unfair to penalize students who otherwise could graduate.

“I do believe the goal is a good one, but we need to be realistic,” Cortines said. Enforcing the plan is “not practical, realistic or fair to the students of 2017. I don’t think we’ve provided the supports to the schools.”

But the college prep requirements still have significant backing within the district and among community activists, who say L.A. Unified must do a better job helping students pass the challenging classes.

L.A. Unified received national attention with its college prep goals, which were approved in 2005. The district allotted 12 years to get there — the entire education of a child who entered the system at that time.

Students in the class of 2017 must earn a C grade or better in a set of courses aimed at making all seniors eligible to apply to the University of California and California State systems. These include four years of English and three years of math, including geometry and intermediate algebra.

Overall, officials said, students have been better served because of the mandate. For one thing, the full set of college preparatory classes has become available at all high schools.

Moreover, the percentage of students completing the minimum college prep curriculum has increased from 15% to 28%, said activists who reviewed district data.

And graduation rates have increased. Last year, the four-year graduation rate for 9th graders was 67% — the latest in a string of improving statistics.

Fewer than half of these graduates, however, would have met the 2017 standard.

Among about 37,000 students remaining in the class of 2017, only 26% are on track to graduate and 17% are repeating 9th grade, according to district research.

The success of students varies widely. At Washington Preparatory High School, for example, 29% of the class of 2017 are on track. At Mendez High School, by contrast, 77% are on schedule.

The push for mandatory college-prep courses was based on the apparent success of San Jose Unified, which had adopted a similar policy. But its gains in college-prep rates were later determined to be inflated by an accounting error. A 2013 Times review of the data showed that most San Jose students never qualified to apply to a state college.

L.A. Unified immediately fell behind in its efforts but stuck to its timeline. Former Supt. John Deasy, who resigned in October, repeatedly insisted that requiring students to get a C or better in these classes was necessary for a diploma to be meaningful.

The effort also had unintended consequences. Because students had to repeat some college prep classes, they had more difficulty fulfilling the required total number of units. In response, the district reduced the number of credits required to graduate. It also was more difficult for some schools to schedule advanced courses, such as calculus. And there was less room in class schedules for popular electives that helped keep students interested in school.

At a Tuesday news conference of activists and others, recent graduate Perla Madera, 20, backed the more stringent standards, but said that her high school failed to provide the help she needed.

“During high school, I was consumed by work, school, chores and baby-sitting,” she said. “I quickly fell behind in school. I was labeled as disobedient.... I was not offered help.”

Instead, she said, an administrator at Mendez told her she was behind on credits and out of step with the school’s mission of higher achievement. He advised her to transfer out of the Boyle Heights school.

“Why didn’t my school or the district ask me if there was a reason for me falling behind?” she said.

Madera received help from outside organizations and graduated on time. She now attends East Los Angeles College.

School board member Monica Garcia, who joined the news conference, said she supports keeping the graduation rules, but she also doesn’t want to deny students diplomas. She cited the budget cuts of the recession as a major factor holding back district efforts. She also said the cultural and logistical challenges of moving to higher standards were huge.

She said one temporary option would be an alternative path to graduation that still promotes academic rigor.

San Jose amended its approach to avoid a graduation debacle. Students were allowed to get a D, even though the UC and Cal State systems require at least a C in each of these classes. And students failing the rigorous courses could transfer to alternative schools and graduate from them.

Activists, who 10 years ago called for the requirements, said Tuesday that they don’t want to see L.A. Unified retreat.

“We are here to demand that LAUSD stay on course and stay committed,” said Maria Brenes, executive director of InnerCity Struggle, a local community organizing group.

The school board is expected to discuss the issue at its meeting next week.

Twitter: @howardblume

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.