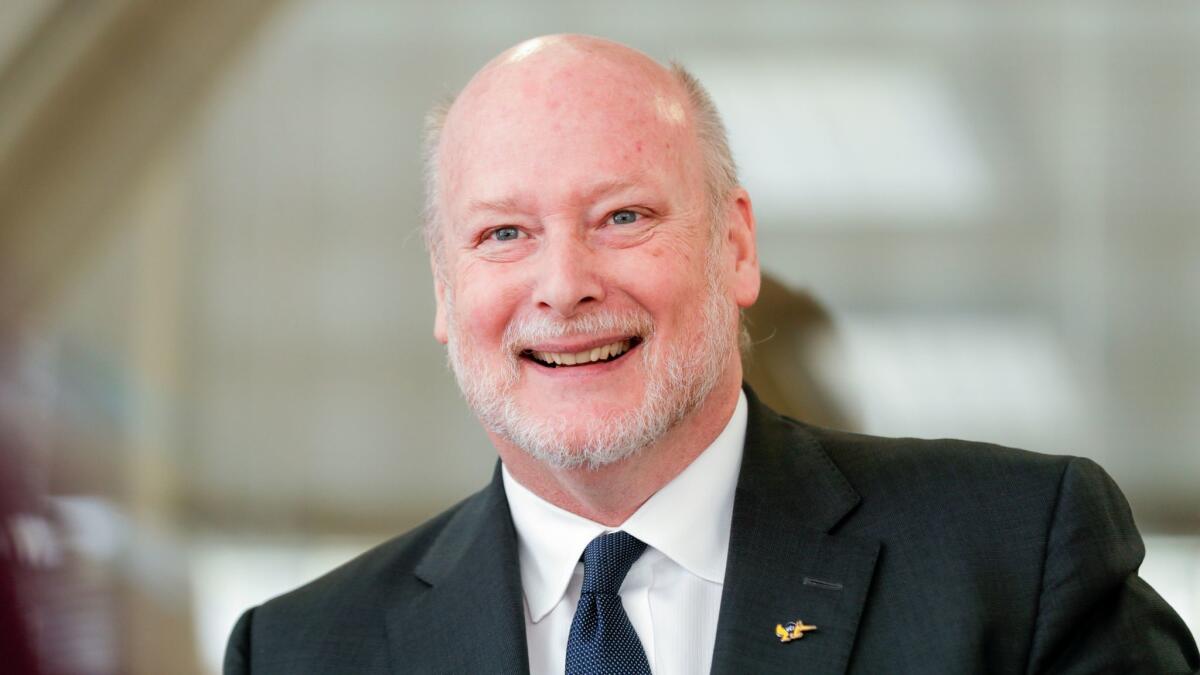

Q&A: UC Irvine chancellor: Students are not âsnowflakes,â but they need to understand free speech

UC Irvine Chancellor Howard Gillman has plenty of experience with free speech issues. His campus has been rocked by controversial appearances of right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, a dust-up with College Republicans and annual skirmishes between supporters of Israel and Palestinian rights. Gillman has taught U.S. constitutional law for 30 years and launched a course on free speech three years ago. Now heâs written a new book, âFree Speech on Campus,â with Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Berkeley law school.

Is student support for free speech eroding?

There has been a change. Iâve been teaching constitutional law for 30 years, but the last five years have felt like a very different environment. When I was growing up it was the antiwar movement and the civil rights movement and Lenny Bruce and George Carlin, and we saw the social benefit of protecting even controversial or offensive speech. This generation hasnât lived through that experience of why broad protections of free speech are helpful for social progress. Theyâve seen it mostly in terms of the internet and the terrible dynamic of social media, so I think they have more appreciation for the psychological harm ⦠of people saying offensive things and less appreciation of the historic value of free speech for a free society.

Some critics say too many students today are fragile âsnowflakes.â

Itâs a very unfair assessment. I spent the last few years teaching undergraduates a course on free speech on campus. These students were fantastic. Theyâve overcome a lot. They are incredibly resilient. Hate speech is incredibly harmful. I donât think weâre going to make any progress deepening the conversation by dismissing those concerns or criticizing these students. Their legitimate concerns have to be acknowledged, and then we see if we can come to some deeper understanding of how you cope both with issues of inclusion and diversity and with issues of the free expression of ideas.

You say hate speech is harmful. Should it be banned?

Hate speech is the real flashpoint in these contemporary debates. The arguments for how hate speech is traumatizing to people are absolutely legitimate. But in the â80s and â90s, 350 colleges and universities passed hate speech codes, and every single one of them that was looked at by a federal court was struck down as unconstitutional. The main concerns have to do with coming up with a definition of hate speech that is not so broad and vague as to allow mere censorship because of a disagreement with ideas. No one has been able to devise that definition.

What should campuses know about free speech?

You canât punish or censor someone merely for expressing an idea. But you can censor or punish if speech becomes harassment, a true threat or incitement. You must allow students to have a right to express their views, including through protests. But campuses can pass time, place and manner restrictions that prevent those kinds of protests from occurring in a way that disrupts campus activities. We believe that campuses can take stronger stands to regulate the kind of speech that occurs in dorms and other places of repose as long as those regulations are viewpoint-neutral. We believe that campuses must allow students to have places where they feel especially comfortable, but not in ways that transform the entire campus into a zone that protects them from the expression of ideas.

Some campuses restrict speech to âfree speech zones.â Your thoughts?

Free speech zones are a troubling concept when they are designed to limit speakers to relatively small and isolated parts of campus. People have a right to express themselves in ways that find an audience.

Trigger warnings?

Trigger warnings are legitimate if they are the choice of a faculty member to help students prepare for what might be a challenging set of topics in a class.... Whatâs inappropriate is for universities to require faculty members to label certain content, even against their best judgment, as being offensive or hateful.

Safe spaces?

The one way the concept is used that is problematic is to treat the campus as a place where people should be safe so theyâre not exposed to ideas they find distressing. As the great UC President Clark Kerr said, we are here not to make ideas safe for students but to make students safe for ideas.

What is your bookâs biggest message?

The concerns that students are expressing are legitimate, and universities must commit themselves to the creation of safe and inclusive learning environments. But part of the learning environment you are creating in higher ed is one where any idea can be expressed, evaluated, contested and engaged. If universities are not fundamentally safe spaces for the exchange of ideas, they will become institutions of indoctrination rather than true education.

Twitter: @teresawatanabe

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.