Offering free computers, a small L.A. school district enrolled Catholic school students from Bakersfield

- Share via

Last spring, Katie Rivera’s daughter came home from the St. Francis Parish School in Bakersfield with some unusual paperwork.

The school was pushing parents to sign their children up for a “unique pilot program” taught entirely online and run by a public school district in Los Angeles County.

Each student who enrolled in the Lennox Virtual Academy would get a free Chromebook computer to use at school, with access to online classes. All parents had to do was fill out the forms, authorizing St. Francis to share information about their finances and their children’s health with the Lennox School District a hundred miles away.

“This partnership is expected to bring many benefits for St. Francis students,” Principal Kelli Gruszka wrote to parents. “...it is IMPERATIVE that every family with students in grades 5th-8th, return the paperwork being sent home today...”

What the letter did not explain was the arrangement’s financial benefits. By enrolling these students, Lennox stood to earn millions in additional state funding. St. Francis would profit, too. As part of the deal, the school would be paid a fee for each participating student.

The proposal was part of an unorthodox expansion plan by a small public school district headquartered three miles from Los Angeles International Airport.

That Lennox had created a virtual school was not so remarkable. Online public schools operate across California in almost every form imaginable. Some cater to home-schoolers; others focus on students who have fallen far behind. Many are charter schools that are supposed to be held accountable by the school boards that authorize them, but a handful are run by public school districts that answer mainly to themselves.

The Lennox Virtual Academy operated in what legal experts have called a murky regulatory environment. Even so, it stood out both for enrolling students already attending school elsewhere and for its willingness, in partnering with Catholic schools, to test the limits of California’s particularly strict interpretation of the separation of church and state.

The description of the pilot program alarmed Rivera, who is an attorney and could tell she was not being asked to sign an ordinary permission slip.

“It had red flags all over it,” she said of the paperwork, particularly one section that stated, “...all of our students in 5th-8th grade will need to be co-enrolled at both schools.”

She grew even more concerned after she asked a St. Francis administrator how it could possibly be legal for a Catholic school to get such expensive technology for free from a public school district, and was told the school was taking advantage of a legal “loophole.” St. Francis officials declined to comment for this story, but the Diocese of Fresno and the Lennox School District defended the arrangement as legal.

Rivera refused to sign the forms.

“There can’t be a loophole in the law that other private schools aren’t using,” she said. “If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.”

Enrollment had been declining in the Lennox School District for over a decade by the time the district decided to open the virtual academy in 2016 as part of a concerted effort to attract more students. By then, the student population had fallen to 5,055, nearly 25% below what it had been in 2006. Lennox employees were being encouraged to recruit children of friends and family, said Supt. Kent Taylor, and officials were eager to welcome students from elsewhere who might want to transfer in.

Lennox Virtual Academy enrolled about 400 students last year, Taylor said.

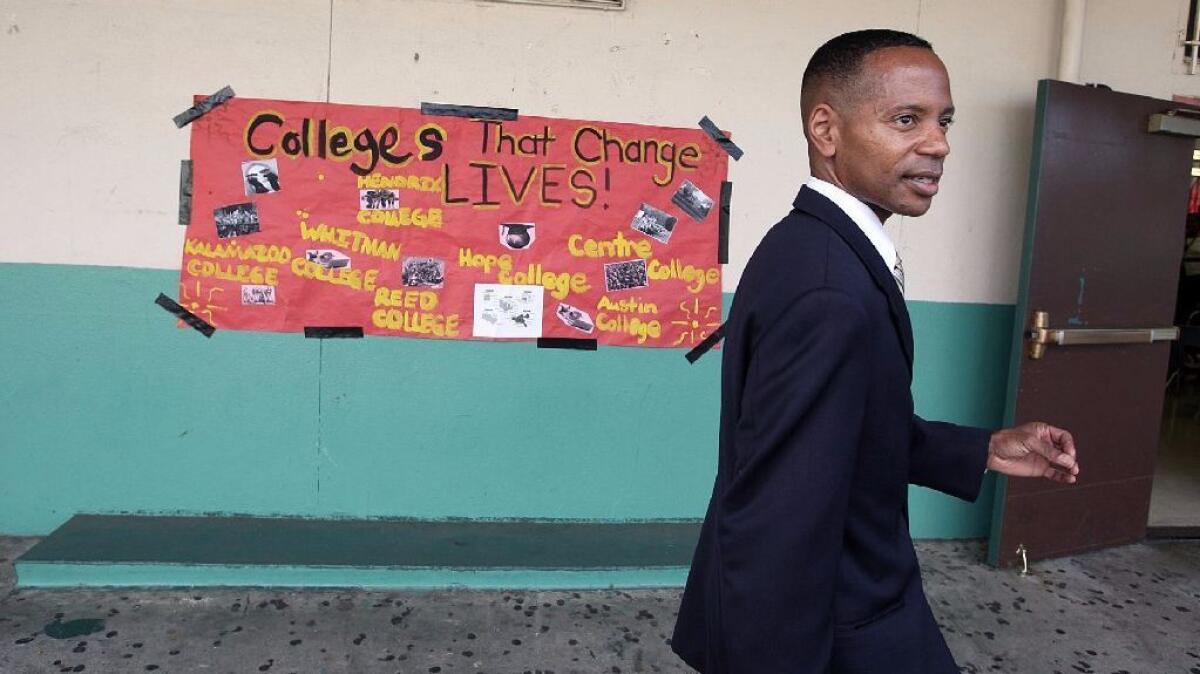

“We’re trying to be on the cutting edge so we can make sure students’ lives get changed and their trajectory in the future can be great,” he said of the online school. “What’s really important here is what the student gets out of this.”

What Lennox got out of it was more kids, and more kids meant more money. That year, according to state education data, the district’s state funding increased by at least $3 million as overall enrollment rose, largely through students signed up for the virtual academy.

Catholic schools nationwide have been struggling with enrollment too, and some have been forced to close. Lennox’s offer of free classroom technology came at an opportune moment.

Like St. Francis, at least three Catholic schools in Southern California enrolled students in the virtual academy, according to interviews. The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles said St. Joseph School in Hawthorne and St. John Chrysostom Catholic School in Inglewood signed contracts with Lennox last school year. Resurrection Academy in Fontana began participating this year, according to the Diocese of San Bernardino.

The partnership with Lennox “is a real positive thing for Resurrection Academy,” said John Andrews, a spokesman for the Diocese of San Bernardino. “I know maintaining enrollment is a struggle there and that having the means to do a technology initiative where you have one device per student is a real challenge.”

Chromebooks for every student, he said, “does create a sense of excitement and definitely makes the school more marketable for families in the Fontana and Rialto area.” Resurrection Academy students are expected to be online at least two hours a day, and Lennox has expanded the course options.

As for the nature of the partnership with Lennox, the diocese vetted it, he said.

The Los Angeles Archdiocese looked hard at the proposal too, said Superintendent of Catholic Schools Kevin Baxter.

There was plenty to like about what Lennox had to offer. Baxter said the school district paid the Catholic schools a monthly fee of $165 for each child enrolled. The district also upgraded the Wi-Fi network at St. John Chrysostom.

Rocio Mendoza, whose two sons attend St. Joseph, said she liked the improvements. Her children seemed to enjoy using the Chromebooks and online classes, and St. Joseph administrators had assured parents that nothing about the school’s emphasis on religious education would change.

“They were still Catholic school students. The only thing was that form they made us sign to get the Chromebooks,” Mendoza said. “We were all sold on it.”

But as the year went on, the archdiocese grew concerned by its interactions with Lennox. Archdiocese lawyers wanted assurance that state and county education officials had approved of the virtual academy and its unusual co-enrollment arrangement. They had questions about the legality of enrolling Catholic school students in a public school program. And they wanted a face-to-face meeting with Lennox officials.

“We had a difficult time kind of getting answers and getting meetings scheduled,” Baxter said. “We thought it was probably in the best interest of our schools to discontinue the partnership.”

At the end of the school year, St. Joseph and St. John Chrysostom exited the program and returned the Chromebooks to Lennox.

Lennox Supt. Taylor described the district’s relationship with the archdiocese as respectful, with both sides working in the best interests of students. “We hope to work with them in the future,” he said.

In Bakersfield, where St. Francis was the only Catholic school that agreed to try out the program, the Diocese of Fresno reviewed Lennox’s proposal and declared it sound, said Diocese Supt. Mona Faulkner.

The Chromebooks came with one requirement, Faulkner said: The Catholic students had to log on to Acellus Academy, the virtual school’s coursework program, for a set amount of time each day. This allowed Lennox to claim to the state that the students, while going to Catholic school, were enrolled full time in the Lennox Virtual Academy.

Several St. Francis teachers and parents said in interviews that the school barely used the Acellus lessons. Although it was receiving money from Lennox, St. Francis proceeded as it always had, charging tuition and teaching its own religion-imbued curriculum.

It’s unclear how much the other schools used the online classes, and Lennox officials declined to say what the district’s contracts required.

On Aug. 4, the St. Francis principal emailed parents to say the school would extend the partnership for another year.

But two weeks later — a few days after The Times contacted St. Francis with questions — the school abruptly reversed itself. On Aug. 18, Faulkner emailed Times reporters to say St. Francis had ended its relationship with Lennox. She acknowledged that Lennox had paid St. Francis and said that the money had gone into a financial aid fund for students, but she declined to say how much the school received.

Asked why the Catholic school had cut ties with Lennox, Faulkner said that the online curriculum offered by the district didn’t meet St. Francis’ standards.

“My only concern as superintendent was whether the curriculum was rigorous enough and had enough depth for our students and the school decided it did not,” she said. “There were certain chapters we were not going to teach at all because they may have differences with our faith.”

This program is not a Catholic school program. This is about the parent having the right to enroll their kids in a public school...

— Lennox Supt. Kent Taylor

As it turns out, Lennox did not pioneer recruitment of students attending private schools.

In the late 1990s, the Cato School of Reason, a Victorville-based charter school for home-schooled children, began to count tuition-paying private school students as its own, often without parents’ knowledge. The participating schools were promised books, computers and a split of Cato’s state funding.

Cato’s enrollment rose to 3,500 students, bringing in millions of dollars in state funding, before its host school district shut it down in 1998 over alleged improprieties.

Taylor, in an interview, said the idea of opening the Lennox Virtual Academy came from a consultant.

From his perspective, the participating Catholic schools were centers where his virtual school students met to do their online coursework. Taylor described those participating as public school students — even though their parents were paying thousands of dollars a year in Catholic school tuition.

The virtual school also enrolled home-schooled students who aren’t affiliated with religious organizations, he said.

“This program is not a Catholic school program,” Taylor said. “This is about the parent having the right to enroll their kids in a public school, and this is any student regardless of ethnicity, gender, LGBT, home-school kids.”

As long as the students who participated were not enrolled in another public school district, there were no legal barriers to their involvement, Taylor claimed.

Lennox district officials declined to answer specific questions about the academy’s revenue and expenses, including the services and equipment provided to the Catholic schools. Asked if the district had sought legal guidance before launching the program, officials said that they had, but declined to provide it.

In an email to state regulators, a Lennox consultant suggested that the district knew it was testing the wall between church and state. He described the Catholic schools as “vendors” that leased property to the Lennox Virtual Academy. Lennox required them, in its contracts, he said, to refrain from offering religious instruction while the Virtual Academy students were working on their “lab sessions.”

It’s questionable whether such sessions were more than perfunctory. At St. Francis, Acellus was used infrequently in some classrooms, and in April the principal emailed teachers urging them to use it more.

“I would like to suggest that each of you try and build 10-15 minutes into your lesson plans daily, if possible,” Gruszka wrote. “We just received our second check from the lennox school district [sic] and we will be at risk to return it if progress is not made.”

By couching the arrangement as one in which Catholic schools were being paid to house and help the students of the Lennox Virtual Academy, the district was operating at the edges of state law, experts said.

California’s constitution places a high wall between church and state, explicitly barring spending public money “for the support of any sectarian or denominational school, or any school not under the exclusive control of the officers of the public schools.” And while partnerships between religious and public schools are fairly common, The Times could find no other examples of students simultaneously enrolled full time in public and private schools.

The more troubling aspect of the arrangement, legal experts said, was that Lennox had included the Catholic school students in its enrollment to draw more state funding.

If the students were receiving a full day of secular schooling, the arrangement might comply with state law, said Berkeley Law professor Stephen Sugarman.

“But where’s the day of substantial non-religious education?” he said. Without meeting that standard, Sugarman said, “it’s not a bona fide distance learning school.”

School districts only qualify for state funding for students who are “genuinely enrolled,” Sugarman said.

Parents weren’t the only ones to raise questions about the partnership. In a May email, a Lennox consultant asked state regulators, “...Would you have any concerns over those students who are dual-enrolled in a private school?” He did not receive a reply.

Asked repeatedly to clarify for this story whether Lennox’s partnerships were legal, California Department of Education officials did not respond.

The U.S. Department of Education, when asked about the legality of this type of dual enrollment, called it a “local issue,” and said that questions should be directed to local or state officials.

For some St. Francis parents, the partnership with Lennox also raised ethical concerns.

Jenny Mancilla, who taught at St. Francis until two years ago, pulled her two children out of the school last month in protest.

“It’s kind of sickening when the people who encouraged this are supposedly of this faith where they should want to instill values and transparency and all that,” Mancilla said. “It’s been a bit sad actually.”

[email protected] | Twitter: @annamphillips

[email protected] | Twitter: @howardblume

ALSO

DACA brought ‘Dreamers’ out of the shadows. Now, some plan to only get louder

Jahi McMath, girl declared brain dead three years ago, might still be technically alive, judge says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.