Deputies change stories on jail visitorâs beating, court records show

Two L.A. County sheriffâs deputies have struck deals with prosecutors that require them to plead guilty to criminal charges and, if called on, to testify against their former colleagues in a case involving alleged beatings of jail visitors, court records show.

The sheriffâs deputies all told the same story.

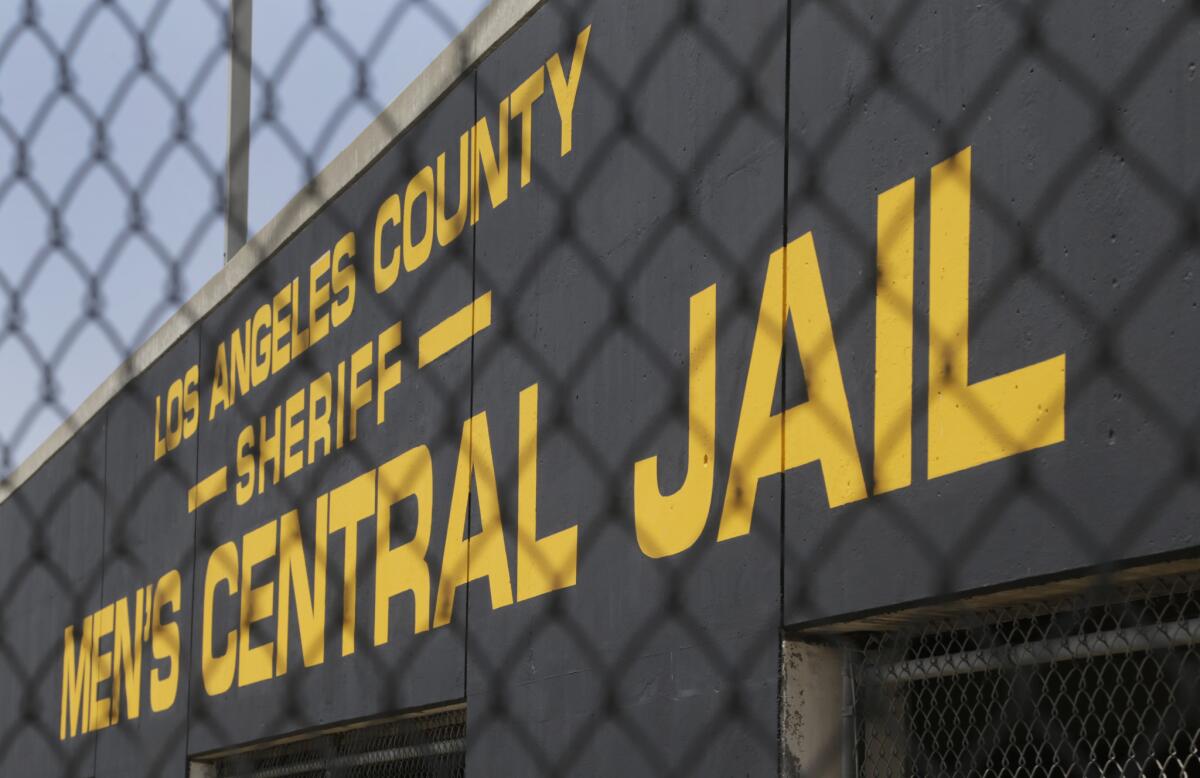

A man visiting his brother in Los Angeles County Jail, they said, fought with them in a waiting area and had to be restrained. The five deputies involved in the struggle adamantly denied the manâs allegations that he had been handcuffed and then beaten.

Their account remained unchanged under scrutiny from internal sheriffâs investigators, the district attorneyâs office and the manâs defense lawyers. No one wavered even when federal authorities obtained an indictment accusing them of assault and civil rights violations.

But two of the deputies have now changed their stories.

With their trial set to open later this month, both have struck deals with prosecutors that require them to plead guilty to criminal charges and, if called on, to testify against their former colleagues, court records show.

Under the terms of the agreement he signed last week, Deputy Noel Womack gave prosecutors a new version of the violent 2011 encounter in a windowless, secluded room in the Menâs Central Jail facility. Deputies, he said, beat the jail visitor even though the man was handcuffed and not resisting as he was held on the floor, according to a copy of the agreement reviewed by The Times.

Womack has agreed to plead guilty to a felony charge that he lied to FBI agents during an interview last month when he told them he did not know if the visitor was handcuffed, the agreement said. He admitted to lying again when he told the agents his supervisor had ordered him to punch the man and a third time when he said the strikes he inflicted on the man had been necessary, the agreement said.

The second deputy, Pantamitr Zunggeemoge, entered a guilty plea earlier this year, court records show. The agreement between prosecutors and Zunggeemoge, who faced several allegations of abuse and dishonesty, was sealed by U.S. District Judge George H. King, keeping its details secret.

But a court filing by another defendant last month said that Zunggeemoge, too, has told prosecutors that the visitor was handcuffed during the incident. In his statement to prosecutors, the filing said, Zunggeemoge said deputies had concocted a story that only one of the manâs hands was cuffed to justify their use of force. The filing also said that Zunggeemoge has agreed to cooperate fully and testify for the government if prosecutors call him as a witness.

Though cutting deals to avoid lengthy sentences is a staple of the justice system, the prosecutionâs ability to extract guilty pleas in this case is striking because expectations of solidarity run deep among law enforcement officers. In their plea agreement with Womack, prosecutors said Womackâs actions highlight the pressures deputies are under to put up a united front.

âWomack continued to lie because he had learned that once a deputy sheriff writes about an incident in a report, the deputy sheriff has to stick to that version of events, even if they are lies, from that point forward,â prosecutors wrote. âWomack understood that he was never supposed to go against his partners.â

Womackâs agreement requires him to resign from the L.A. County Sheriffâs Department, and he will be banned from working in law enforcement. Prosecutors, for their part, will recommend to the judge that Womack receive no time in prison, according to his plea agreement. The judge could opt to disregard the suggestion and sentence Womack to as many as five years in prison, court documents show.

With Zunggeemogeâs agreement sealed, what recommendation, if any, prosecutors will make on his behalf is not known. His attorney and Assistant U.S. Atty. Brandon Fox declined to comment.

The plea agreements mark the first time in the last two decades that a sheriffâs deputy has been convicted in federal court of crimes related to excessive force, a spokesman for the U.S. Attorneyâs office said. Last year, the office secured convictions against seven sheriffâs officials accused of obstructing the FBIâs investigation into claims of brutality by deputies in the jail.

The guilty pleas have scrambled the makeup of the approaching brutality trial, which is scheduled to begin June 16. In securing the deputiesâ help, prosecutors scored a potentially potent advantage in their effort either to extract more guilty pleas or convict the three remaining defendants at trial. Without the firsthand accounts from the deputies, the case would rest heavily on the ability of the beaten man and other alleged victims to convince jurors of what happened.

But Joseph Avrahamy, an attorney representing one of the other defendants, Sgt. Eric Gonzalez, a supervisor at the jail visitor center on the day of the incident, said the about-face by Womack and Zunggeemoge are transparent bids to protect themselves at the expense of the others.

âThey are going to have serious credibility issues,â Avrahamy said of the pair. âThey have been very consistent throughout in their accounts of what happened and now, suddenly, theyâre changing their stories. I think a jury will be able to see right through that. There was never a motivation for them to lie before. Now there is.â

Along with Womack, Zunggeemoge and Gonzalez, the grand jury indictment accuses deputies Sussie Ayala and Fernando Luviano of civil rights abuses. Gonzalez, Ayala and Luviano have pleaded not guilty.

Luvianoâs attorney, Bernard Rosen, acknowledged that the decision of the two deputies to cooperate with prosecutors poses potential problems. But he downplayed the significance of what they might testify to on the witness stand, saying their new accounts of the incident âsupport muchâ of what Luviano contends occurred. Rosen declined to elaborate.

âAny time the government tells a jury theyâve got more than one witness, it makes things more difficult,â Rosen said. âMy client insists heâll be going to trial and is confident heâll be exoneratedâŚ. Some people look forward to their day in court. Others donât.â

The allegations against the group stem from several encounters with visitors to the Sheriffâs Departmentâs main jail facility in 2010 and 2011. In each of the episodes, some or all of the deputies are accused of detaining people without legitimate reasons and, in all but one of the incidents, assaulting them in a room deputies used during work breaks.

Prosecutors portrayed Gonzalez in the indictment as a ringleader who âwould maintain, perpetuate and foster an atmosphere and environment ⌠that encouraged and tolerated abuses of the law by deputies.â

The case centers on the altercation in late February 2011 with Gabriel Carrillo. Carrillo, who had come to jail to visit his brother, was detained with his girlfriend after Zunggeemoge became suspicious that the woman was carrying a cellphone in violation of jail rules.

Carrillo said something combative that angered one of the deputies, which led to the beating, according to prosecutorsâ account. Based on the deputiesâ reports and their testimony in court proceedings, the Los Angeles County district attorneyâs office pursued a criminal case against Carrillo on charges of assaulting law enforcement officers.

Days before the trial, the district attorney suddenly dropped the charges. Carrilloâs attorney found evidence he said showed that Carrillo had suffered injuries on both his wrists consistent with being handcuffed during the struggle. The county later paid Carrillo $1.2 million to settle a civil lawsuit.

In the statement he gave prosecutors as part of his plea deal, Womack said he copied another deputyâs report of the incident involving Carrillo to make sure his account was in line with the others. He added that he watched as Gonzalez later laid out all the deputiesâ reports on a table to compare them and âensure their consistency.â

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.