Column: A charter school report card: They cause problems. But for many families they’re the solution

- Share via

Echo Park resident Jackie Goldberg, a grandmother, great aunt and candidate for school board, says if she had school-age children, she would not send them to a charter school.

Not even the one in her neighborhood that has been called one of the best in California.

For the record:

8:30 p.m. March 9, 2019A previous version of this article said the runoff election in the L.A. Unified school board race is next month. The runoff is May 14.

I might be a little biased here because I know the founder of Gabriella Charter School. But parents are impressed, too. And Gabriella, which has a waiting list of students trying to get in, has won a string of accolades over the years, including a Distinguished Schools Award last year from the state.

Still, said Goldberg, she’d pick another school for her kids.

“Right now, I would, because there are wonderful magnet programs and some of them are not filled, and I would prefer that, if I didn’t like the neighborhood schools,” she said.

Why not the charter?

“Because I know personally that my decision would unintentionally harm other children,” Goldberg said.

In the six-day strike by L.A. Unified teachers in January, there were two villains.

One was California’s low national ranking in funding per pupil.

The other was charters.

United Teachers L.A., the teachers union, argued that charters rob traditional schools, leaving them with some of the most challenged students but less money to serve them. The union, which backs Goldberg’s run for school board, put the theft at nearly $600 million a year, the amount of funding that follows students to charters even as fixed costs remain for traditional schools. About one in five LAUSD students attend one of the district’s more than 200 publicly funded, privately operated charters.

Myrna Castrejon, who runs the California Charter School Assn., told me she looked out her downtown L.A. office one day and saw “15,000 teachers screaming” about billionaires taking over the schools with their pro-charter movement.

Rather than respond to the targeting, she said, charter schools focused on the daily task of educating children. But she added that she agreed with striking teachers that California has shamefully underfunded all of public education.

“I got chills because this was exactly the wake-up call we needed,” she said.

Charters, like traditional schools, hit all the letters on the report card, from A to F. New legislation demanding more regulatory oversight is a good thing, and there’s a call for a moratorium on new charters while their impact on traditional schools is studied.

Goldberg, who was the leading vote-getter in her school board race last week and moves on to the runoff on May 14, would tip the LAUSD school board from pro-charter to pro-union if she wins. Among other new rules she’d like to see, she told me, was one in which traditional schools don’t lose money when students jump to charters.

So does this mean the charter wave is beginning to wash out?

Probably not. There’s money and passion on both sides of the divide, and compelling arguments, too. Charters do have an impact on traditional schools, but they also offer options to low-income families of color that can’t afford to move to high-performing districts or pay for private school.

Although charters were being vilified during the strike for creating so many problems, they came into being to solve problems — namely, as laboratories in the search for new models to reverse years of low performance in traditional public schools.

Liza Bercovici, the founder of Gabriella, was once an attorney who could not have imagined running a school. Twenty years ago, she lost her 13-year-old daughter, Gabriella, in a bike accident during a family vacation. Gabriella loved to dance and wanted to be a teacher. Bercovici gave up her law practice and established a nonprofit dance academy in her daughter’s memory near MacArthur Park.

The dance program grew from a few students to thousands, just as the charter movement was taking root in Los Angeles. Bercovici became intrigued by the idea of building a curriculum and a culture of high expectations around the discipline and fun of ballet, jazz and contemporary dance.

Declining enrollment in LAUSD left open spaces in formerly overcrowded schools, and in 2005, Gabriella Charter opened its doors on a portion of the Logan Elementary campus in Echo Park. At that time and to this day, there’s friction around co-located schools, but those issues were not quite as contentious back then, and many parents wanted better options.

“We exist because the state, in its wisdom, wanted to change up how education was being delivered and create new alternatives and choices for parents,” said Bercovici. “Our school, with its emphasis on dance, was the perfect example of this.”

Bercovici said she doesn’t understand district budgeting well enough to judge the union claim that charters drain millions from traditional schools. She said she supports the district and the efforts of teachers with class sizes that are way too big, and she believes their pay “is a joke.”

But her mission and that of the Gabriella staff is simply to deliver the best possible education to students, the vast majority of whom come from low-income families.

“I really think we should trust our parents to make decisions about what kinds of schools they want their kids to attend,” said Bercovici.

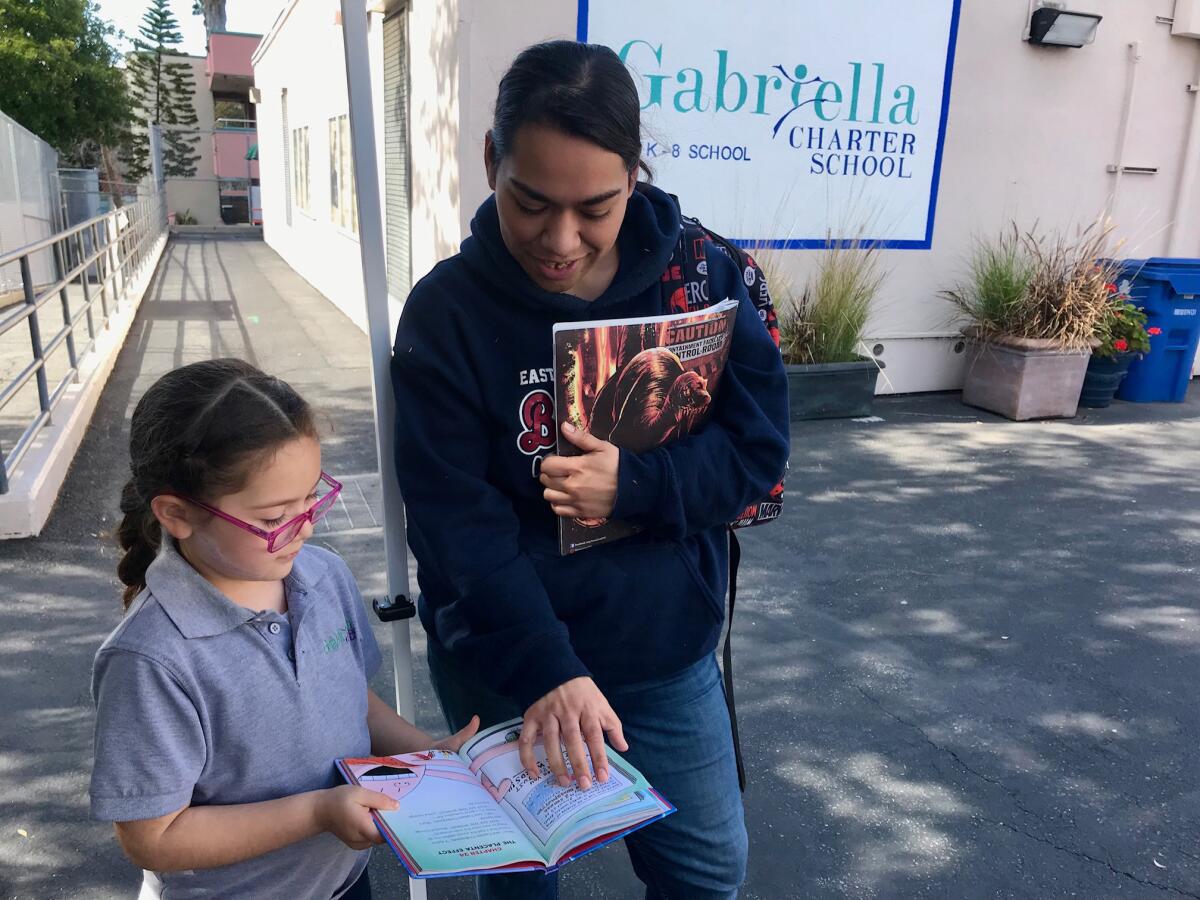

I met with three Gabriella parents at the afternoon pickup on Thursday, all of whom once had children at other schools but made the switch to Gabriella and are grateful for it.

Ireri Ray lives in East L.A. but said she’s happy to make the drive with her kids.

Edilia Morales said she takes two buses each way to get her kids to and from Gabriella.

Stephanie Briseno has two Gabriella students, including a special-needs son who struggled in a regular school but has prospered at the charter. She lives in Koreatown but doesn’t mind the commute, which is often by public transit.

UCLA education professor and researcher John Rogers said a school like Gabriella is a good example of the early imperative of charters — try something different and see if it works. But recent charter growth has been fueled more by a “Wild West” drive to compete with traditional schools for students, he said, without enough consideration of the impact or the goal of expanding the menu of innovative approaches.

“I think when UTLA responds in a negative way, that’s where they’re right,” Rogers said. “Competition creates instability, and instability harms schools like the one in Pacoima.”

He was referring to Telfair Elementary, where I spent several weeks last fall. That school, which has the most homeless students of any campus in LAUSD, is surrounded by charters. Principal Jose Razo has tried his best to compete even as he loses students and is forced to make hard decisions on class sizes. On most days, the library is closed, the nurse’s station is vacant, and students suffering the effects of trauma, family dysfunction and unstable housing don’t have access to a psychiatric social worker.

We keep fighting over the best approach to better schools when the obvious problem is not the schools, or whether they’re charter or traditional, so much as an economy that has made poverty in urban districts the norm.

In different ways, I was as impressed by what Telfair does, day in and day out, as I am by what Gabriella Charter has accomplished.

There’s a place for both, and a need for greater support of all public schools.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.