California officials say housing next to freeways is a health risk ‚ÄĒ but they fund it anyway

It’s the type of project Los Angeles desperately needs in a housing crisis: low-cost apartments for seniors, all of them veterans, many of them homeless.

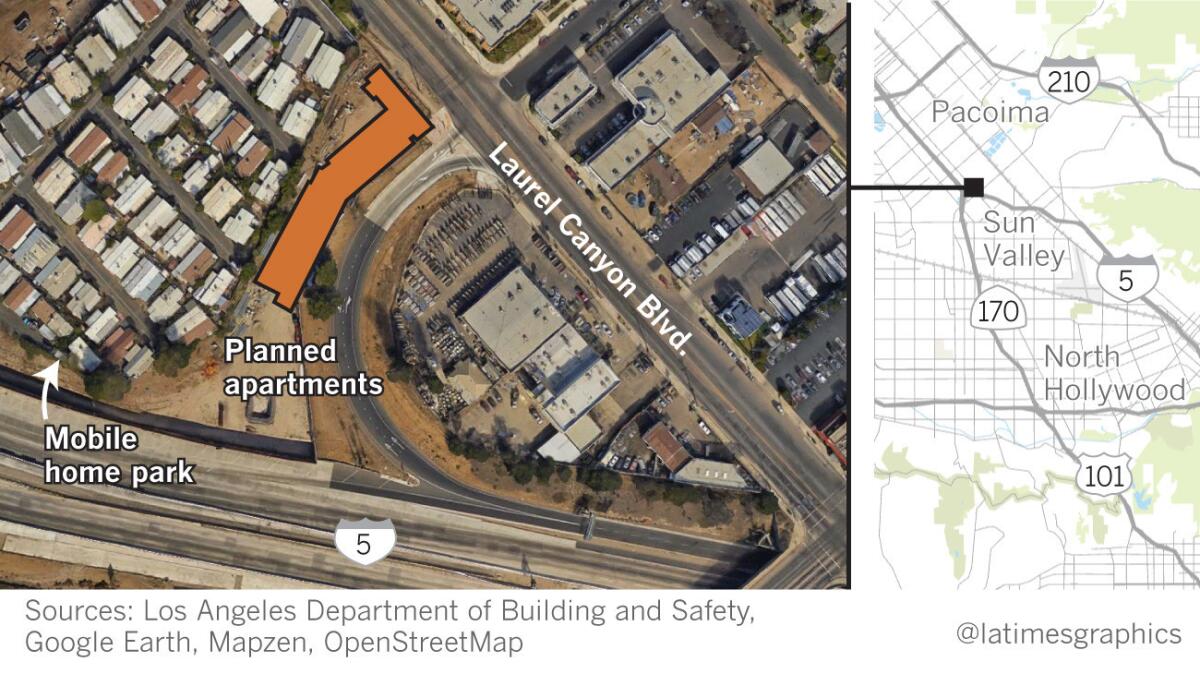

There’s just one downside. Wedged next to an offramp, the four-story building will stand 200 feet from the 5 Freeway.

State officials have for years warned against building homes within 500 feet of freeways, where people suffer higher rates of asthma, heart disease, cancer and other health problems linked to car and truck pollution. Yet they’re helping build the 96-unit complex, providing $11.1 million in climate change funds from California’s cap-and-trade program.

The Sun Valley Senior Veterans Apartments is one of at least 10 affordable housing projects within 500 feet of a freeway awarded a total of $65 million in cap-and-trade money since 2015, a Times review of records found. Those developments will place hundreds of apartments for homeless people, veterans and families near freeways in Los Angeles, the Bay Area and the Central Valley, some less than 100 feet from traffic.

California’s support for those projects shows how policies created to cut greenhouse gases and ease the housing crunch are also putting some of the state’s neediest residents at risk from traffic pollution. It's one way public dollars are helping finance a surge in residential development near freeways, where Los Angeles and other California cities have permitted thousands of new homes in recent years.

How close do you live to the freeway? ¬Ľ

State officials acknowledge that some cap-and-trade money, collected from companies that buy permits to emit greenhouse gases, will put residents near elevated levels of pollution. But they say dense housing near bus and rail lines is crucial to meeting California’s climate goals, by getting cars off the road.

Even in places with poor air quality, they argue, residents’ health will improve from walking and biking more. And they say the dangers from living near freeways can be reduced with anti-pollution design features recommended this year by state air regulators, including sound walls, vegetation barriers and high-efficiency air filters that remove some of the harmful particles from vehicle exhaust.

‚ÄúWhen those strategies are employed, the environmental and public health benefits of these projects far outweigh the negatives,‚ÄĚ said Ken Alex, a senior advisor to Gov. Jerry Brown who chairs the Strategic Growth Council, the agency that distributes cap-and-trade funds to affordable housing developers.

California‚Äôs decision to subsidize low-income housing near freeways alarms some health scientists, who point to years of studies that link roadway pollution with a growing list of illnesses ‚ÄĒ and billions in healthcare costs. They say air filters and other mitigation measures are not enough to protect residents, especially children, whose lungs could be damaged for life, and seniors, who could die early from heart attacks.

‚ÄúI see the economic incentives for doing this,‚ÄĚ said Beate Ritz, an environmental epidemiologist at UCLA who has studied the health effects of traffic pollution for more than two decades. ‚ÄúBut it‚Äôs kind of stupid, because we all know we will pay for it with long-term health effects. Somebody has to pay for the costs of diabetes, of cognitive decline or strokes. This is just creating a huge amount of costs for society in the long run.‚ÄĚ

Construction is expected to start within weeks on the Sun Valley project, capping a decade of debate that pitted the need for more housing against the health of people who would live there. Proponents say those apartments will be far superior to life on the street, with higher-rated air filters and a buffer ‚ÄĒ dozens of trees, a sound wall and a parking lot ‚ÄĒ separating residents from pollution.

Despite those measures, some locals argue the freeway is simply too close.

‚ÄúThese vets are going to be sucking in these diesel fumes. It‚Äôs going to shorten their lives,‚ÄĚ said Mike O‚ÄôGara, who lives eight blocks away and is a veteran of the U.S. Naval Air Forces. ‚ÄúWhat a hell of a great reward for serving their country.‚ÄĚ

Unpleasant choices

The Sun Valley project offers a window into the unpleasant choices faced by politicians, real estate developers and nonprofit groups as they struggle to counter rising rents and a surge in homelessness, which grew 23% this year across Los Angeles County, to nearly 58,000 people.

Los Angeles, a city crisscrossed by freeways, is embarking on a $1.2-billion plan aimed at financing 10,000 homes for homeless people. Land next to those corridors ‚ÄĒ often cheaper and less likely to spur outcry from neighborhood groups ‚ÄĒ will be tempting to build on.

If policymakers put low-cost housing next to freeways, they will place some of their poorest constituents in locations where pollution can be five to 10 times higher, saddling them with the health consequences. But if they prohibit new construction in those areas, they could make things tougher for people trying to get off, or stay off, the streets.

Of the roughly 2,000 affordable housing units approved in Los Angeles in 2016, 1 in 4 was within 1,000 feet of a freeway, according to figures from the Department of City Planning. Officials are weighing whether to build homeless housing on at least nine city-owned properties within 500 feet of freeways ‚ÄĒ including one that‚Äôs less than 200 feet from the sprawling 110-105 freeway interchange.

Housing advocates point to studies that link homelessness to early deaths from drug use, respiratory disorders and other health problems. Homeless individuals are also less likely to obtain access to healthcare, mental health services and substance abuse counseling than those who have shelter, said Mike Alvidrez, chief executive of Skid Row Housing Trust, which has built 1,800 units of housing since 1989 ‚ÄĒ including one building next to the 10 Freeway.

‚ÄúWe know that people die sooner if they don‚Äôt get off the street and into housing. We just know that,‚ÄĚ he said. ‚ÄúSo if you have a solution that going to prolong someone‚Äôs life ‚ÄĒ irrespective of whether it‚Äôs the worst place you could put it, next to a freeway or next to two freeways ‚ÄĒ if you don‚Äôt have another option, that‚Äôs what you do.‚ÄĚ

Across the region, homeless people are already living near freeways ‚ÄĒ in tents tucked along sound walls, in campsites obscured by shrubbery. Jason McKenney, 34, said he has spent some nights in North Hollywood Park, which runs along the 170 Freeway.

Sitting under a tree nursing an injured leg, the onetime construction worker said he would have no qualms about moving into a building next to a freeway, if it had cheap rents and counseling for substance abuse.

‚ÄúI would jump at that chance,‚ÄĚ he said.

Apartments near transit

With climate change now a top priority, California has embraced policies to cut carbon emissions by packing dense housing near jobs and transit. State leaders have set aside nearly $700 million from the cap-and-trade program to finance transit-oriented developments and infrastructure.

The planned Sun Valley development is on a noisy stretch of Laurel Canyon Boulevard with high-speed traffic and few walkable businesses. But because it’s near a bus stop, the project was eligible for cap-and-trade funds.

To boost transit use near the senior housing complex, a portion of those funds will go toward free bus and rail passes for the tenants, as well as new crosswalks, sidewalks and wheelchair ramps.

Like many projects that have received cap-and-trade money, the project is in a location that already endures a heavy pollution burden, which helped it qualify for state funds. The application for cap-and-trade money acknowledged the neighborhood has high rates of asthma.

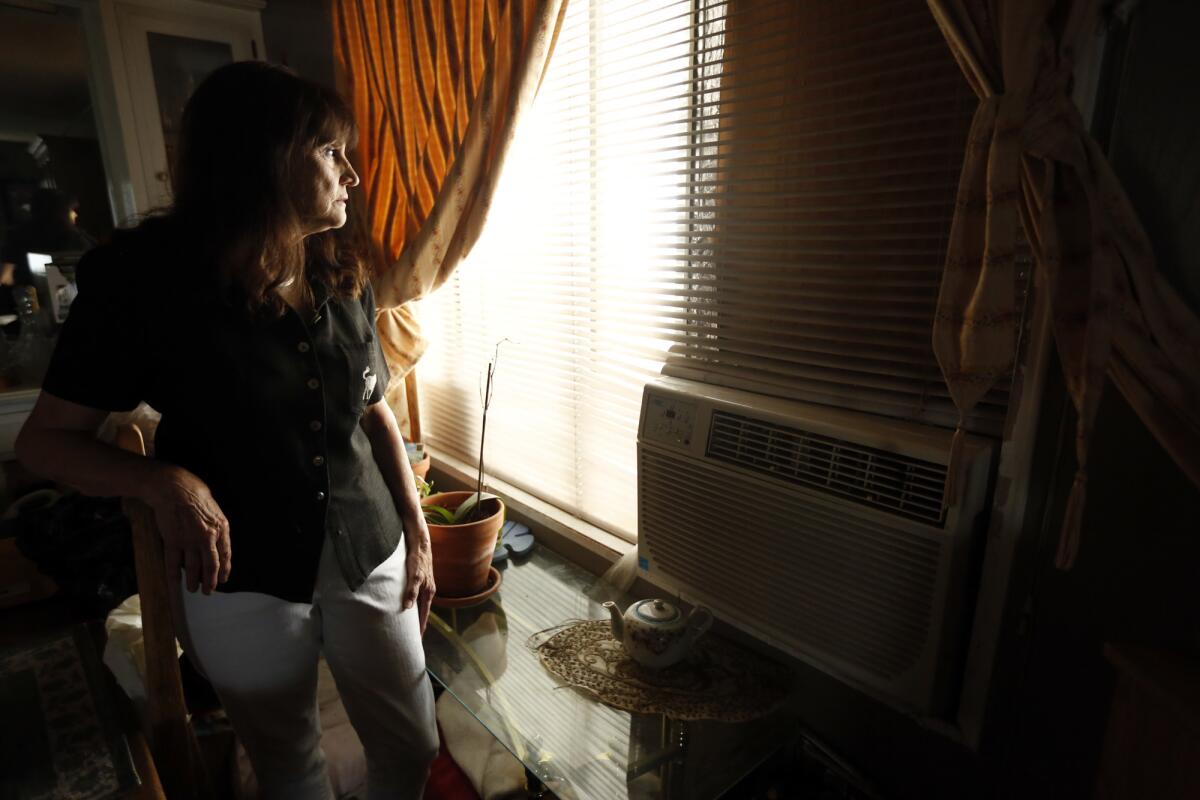

Some in the neighborhood, such as 75-year-old Joan Winget, see the freeway as a serious health threat. Diagnosed with emphysema in 2012, Winget has lived more than 20 years in a mobile home park right next to the senior housing site.

The retired property manager smoked cigarettes until 1979, and her health issues are linked at least in part to that habit. But she worries her medical problems have been exacerbated by pollution from the nearby 5-170 freeway interchange, whose swooping ramps can be seen from the property’s driveway.

Each day, about 200,000 vehicles on the 5 pass her home. To protect herself, Winget keeps her doors and windows closed 24/7 and the air conditioning running around the clock. She misses the days when she let a breeze blow through her home late at night.

‚ÄúI hate it,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúI love fresh air. I like getting outside. I don‚Äôt like being stuck in the house all the time. I might not be getting the greatest air in here, but it‚Äôs worse outside.‚ÄĚ

Regulators say decades of tough clean-air rules have slashed tailpipe emissions, reducing risks to people near freeways. But some scientists warn those health improvements will be undercut by the state’s push to concentrate high-density housing near transit hubs, which often sit near major roadways.

A 2016 study projected state climate policies would increase the number of preventable deaths from heart disease in Southern California by placing more people near traffic pollution. Establishing buffers between homes and heavy traffic, in contrast, would decrease heart disease deaths, especially among the elderly, according to the study by researchers from USC, the California Department of Public Health and several other institutions.

The state Air Resources Board ‚ÄĒ which since 2005 has recommended municipalities ‚Äúavoid siting‚ÄĚ homes within 500 feet of freeways ‚ÄĒ oversees the spending of billions of dollars in cap-and-trade funds by a dozen state agencies. But the board does not select the affordable housing projects that get the money. Those decisions rest with the Strategic Growth Council, a committee appointed by the governor and state lawmakers.

Records show the Strategic Growth Council voted unanimously to award funds for apartments next to the 110 Freeway in Los Angeles, housing along Highway 99 in Turlock and a 135-unit building in San Jose that’s just 25 feet from Highway 87, a location a state analysis ranks in the 95th percentile for diesel emissions.

At least one member of the panel, Manuel Pastor, said he was unaware he had voted for housing so close to freeways.

Pastor, who directs USC’s Program for Environmental and Regional Equity and has written on the health implications of building near roadway pollution, said the issue never came up when the projects were being considered.

‚ÄúYour pointing out the exact location of these projects is the first time it has come to my attention,‚ÄĚ said Pastor, an appointee of State Senate leader Kevin de Le√≥n. ‚ÄúI have not until now asked for a map of where these things are.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄėPoor planning and bad zoning‚Äô

The push to build homes on the Sun Valley site began more than a decade ago, just as Los Angeles city officials were starting to reckon with the health risks posed by freeway-adjacent development.

Initially, the zoning for the site allowed for just three homes. The City Council hiked that number to 26 in 2008, at the request of the property’s owners. Three years later, the same developers asked the city to increase the number again, taking it to 96.

Each step of the way, there were warnings about freeway pollution ‚ÄĒ first from planning commissioners, then neighbors, and finally the South Coast Air Quality Management District. Early on, one mayoral appointee called it an example of ‚Äúpoor planning and bad zoning.‚ÄĚ

But the developers had a champion in U.S. Rep. Tony Cardenas, who represented the area.

Cardenas and two of his allies, then-State Sen. Alex Padilla and then-Assemblyman Raul Bocanegra, urged city leaders in 2013 to allow a 96-unit elder care facility to go up on the site. All three have received a steady stream of political contributions from developers, architects and others who worked on the Sun Valley development ‚ÄĒ at least $70,350 over the last 15 years, a Times review of donations found.

The elder care project was approved, and in 2015, the owners sold it for $3.5 million, more than three times the amount paid in 2006, when only three homes could be built on the site.

Neither Cardenas nor Bocanegra would comment for this story. Padilla, now California‚Äôs secretary of state, said he supported the project because it offered ‚Äúaffordable living options for senior citizens.‚ÄĚ

Businessman David Spiegel, one of the project‚Äôs developers at the time, said he followed the city‚Äôs rules. ‚ÄúThere are hundreds of thousands of units that have been and are currently being built on the freeway,‚ÄĚ he said, ‚Äúso any impacts must be acceptable to city, state and federal agencies.‚ÄĚ

Sealing windows shut

The property was purchased by the East L.A. Community Corp., a nonprofit housing developer with experience putting low-income housing next to freeways. ELACC, as the group is known, had already built 33 apartments for homeless veterans along the 5 Freeway in Boyle Heights. At that location, windows facing the freeway are sealed shut and the air conditioning system has higher-rated filters.

Isela Gracian, the nonprofit group’s president, said many of L.A.’s low-income neighborhoods were carved up by freeways decades ago. That, she said, makes it difficult to find properties far from car and truck pollution.

‚ÄúNot every piece of land is available to us,‚ÄĚ she said. ‚ÄúWhoever currently owns the land has to be willing and open to selling the property. It‚Äôs not like we can walk the streets and say, ‚ÄėThis is a better location ‚ÄĒ let‚Äôs swap the project and move it over here.‚Äô ‚ÄĚ

Still, one agency in Los Angeles County has managed to avoid putting its money into projects along freeways.

The county’s Community Development Commission, which provides tens of millions of dollars in low-interest loans to affordable housing developers each year, decided in 2008 that it would not allow its money to finance projects within 500 feet of a freeway.

Kathy Thomas, who heads the agency, said that decision was made in response to warnings about the health hazards of traffic pollution from the Air Resources Board and other regulators. Yet even with that limitation, the commission finances hundreds of units of housing each year ‚ÄĒ and receives more requests for money than it has to lend, she said.

‚ÄúWe have not had any difficulty finding projects,‚ÄĚ Thomas said in an email. ‚ÄúOur freeway buffer requirement is well-known among developers and we really don‚Äôt get any pushback.‚ÄĚ

Thomas said it would be ‚Äúnegligent‚ÄĚ for her agency to knowingly put low-cost housing next to freeways and undermine the county‚Äôs work in reducing ‚Äúthe cost burden of frequent users on the healthcare system.‚ÄĚ

Some officials want similar conditions on the spending of cap-and-trade funds.

Dean Florez, a former state senator who sits on the Air Resources Board, said California should stop using cap-and-trade money for housing near freeways. Those projects, he said, ‚Äúwill endanger people‚Äôs lungs for decades.‚ÄĚ

The Strategic Growth Council is moving ahead without such restrictions as it accepts applications for another $255 million in affordable housing funds.

Agency officials will score projects by proximity to transit, greenhouse gas reductions, walkability and other criteria. One thing they won’t measure is how close the projects are to freeway pollution.

Times staff writers Doug Smith and Jon Schleuss contributed to this report.

Twitter: @TonyBarboza

Twitter: @DavidZahniser

UPDATES:

Dec. 18, 9:50 a.m.: This article incorrectly says Kathy Thomas heads Los Angeles County’s Community Development Commission. She heads the agency’s Economic and Housing Development Division.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.