L.A. Affairs: I had my reasons for not dating white men. Then something changed

HyunJung Yi / For The Times

- Share via

“You look terrible.” My mother zipped up my dress, which sagged at the chest, exposing the bony knobs of my sternum. “Is law school stressing you out that much?”

She hadn’t seen me since I’d left for UCLA the previous fall, and I was back home in Ohio for my brother’s August wedding before heading back to school.

“I liked someone more than he liked me, so I needed to end it,” I admitted.

I was ready to marry my girlfriend. Would she say yes to my Disneyland proposal? Would our relationship blossom after spending a perfect day in the Happiest Place on Earth?

My mother paused, then said, “You’re my daughter.”

She didn’t probe any further, true to the privacy she’d always extended to me and kept for herself. Besides, she had always said, “Koreans don’t date.”

You studied, and when your career was at the right place, you met a suitable person with whom you’d spend the rest of your life. What was the point of dating? Growing up as one of the few Asians in my rural and overwhelmingly white town, this wasn’t a problem as I had few to no high school suitors. My college experience lent itself to brisk dalliances, but my tight group of friends prioritized our sisterhood over serious relationships.

My law school boyfriend had left me no choice. During our early 1L (first year of law school) days, I thought I’d found my soulmate. Like me, he was Asian American and politically progressive. We had both gone to law school to pursue public interest law, scorning classmates whose sole ambition was to land a job at a big firm and make six figures upon graduation.

Soon, however, small relationship cracks appeared, such as his tendency to yawn during what I thought was an interesting conversation or his reluctance to make the drive from his apartment in West L.A. to mine in Westwood. After almost a year of dating, I’d be lying if I said it took me by surprise when he said he wanted an open relationship.

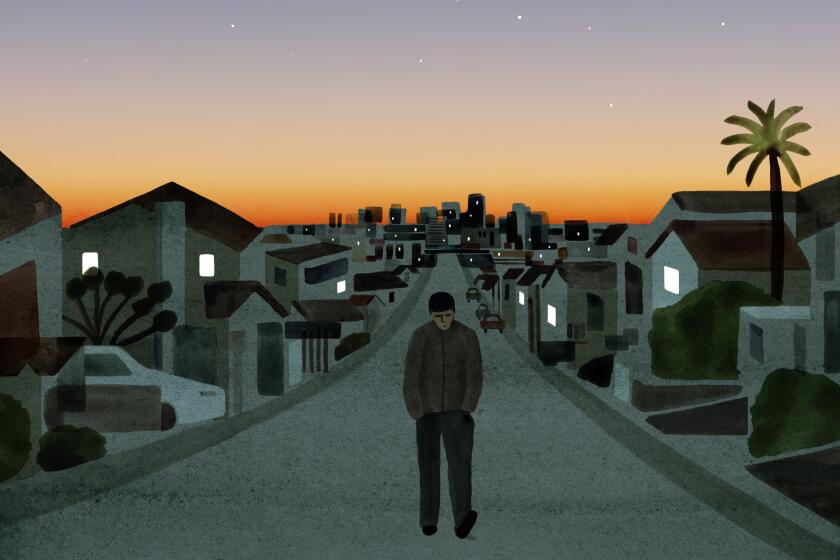

Although my boyfriend’s declaration wreaked havoc on my heart, I plunged myself into my first summer in L.A., learning that there was much to discover east of the 405. It was 1992, and rage and frustration still simmered in the rubble and singed buildings from the recent uprising. My newfound community had suffered the brunt of a discontent born of decades of inequality, not of our making.

While my classmates spent their evenings in box seats at Dodger games hosted by their Century City law firms, I taught English in a strip mall on 8th Street in L.A. — at the time the headquarters for the Korean Immigrant Workers Advocates. This was probably the only useful thing I could offer the nascent nonprofit, as my Korean language skills were lacking and, despite my ideals, I had little experience in community organizing.

After the end of my five-year relationship, I was back in the dating game. Thankfully I met a handsome guy on Bumble.

In an effort to educate me, my boss dispatched me to meetings throughout the city so I could learn from more experienced activists who were grappling with how to rebuild their communities in the aftermath of the uprising. One mid-July day, he sent me to meet with a group that was strategizing about raising the state minimum wage as a possible solution. I overheard people wondering why a certain legal aid lawyer wasn’t there yet. When he finally arrived, he struck me as being a little irreverent in contrast to the earnestness of the other advocates. Still, I noticed he offered good insights, and the rest of the room seemed to respect him.

He happened to be parked next to me in the tiny lot outside the building. His sparkling hazel eyes were friendly. “How do you like law school?” he asked me. “Not at all,” I responded.

“Being a lawyer is a lot more fun. Just stick with it,” he assured me.

As summer wound to a close, I sat in my office, sad to return to law school, sad about my unsettled love life. Our office manager yelled to me, “You’ve got a call!” which she put through. It was the legal aid lawyer, wondering if I was free for lunch.

Of course I was. I needed a public interest lawyer mentor. We had lunch at Ocha in Koreatown. And then he took me to the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library in Jefferson Park, famous for its Oscar Wilde collection. As we sat on the giant roots of a Moreton Bay fig tree and talk flowed easily and effortlessly, it occurred to me that maybe this was more than a sharing of ideas. Two days later, he invited me to the beach. By our third date, we were making out to Beethoven at the Hollywood Bowl.

There was only one problem: He was white, and I had made a decision a few years prior that my politics wouldn’t allow me to date a white guy. I would need to figure this out.

I felt at home with her. I hoped she felt the same way. She was a kindred spirit, and I was falling for her and L.A. too.

Being back home in Ohio, away from L.A., gave me the change I needed to clear my head. The bracing presence of my mother — what she lacked in softness she made up in her clear directness — melted away any ambiguities. I liked this guy. He was handsome. He was romantic. He had wonderful hands and a melodic voice. But more than anything, I liked how safe he made me feel.

Flying back to L.A., I made a decision. It was truly over with my law school ex. Open relationships were not for me. As soon as my plane landed, I called the lawyer. “I’m not into games,” I told him.

“Neither am I,” he replied.

Five years after the L.A. uprising, we got married, and we have been together ever since.

The author is a civil rights attorney at Disability Rights California. She lives in Northeast L.A. Find her on Instagram: @willa.paak

L.A. Affairs chronicles the search for romantic love in all its glorious expressions in the L.A. area, and we want to hear your true story. We pay $300 for a published essay. Email [email protected]. You can find submission guidelines here. You can find past columns here.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.