- Share via

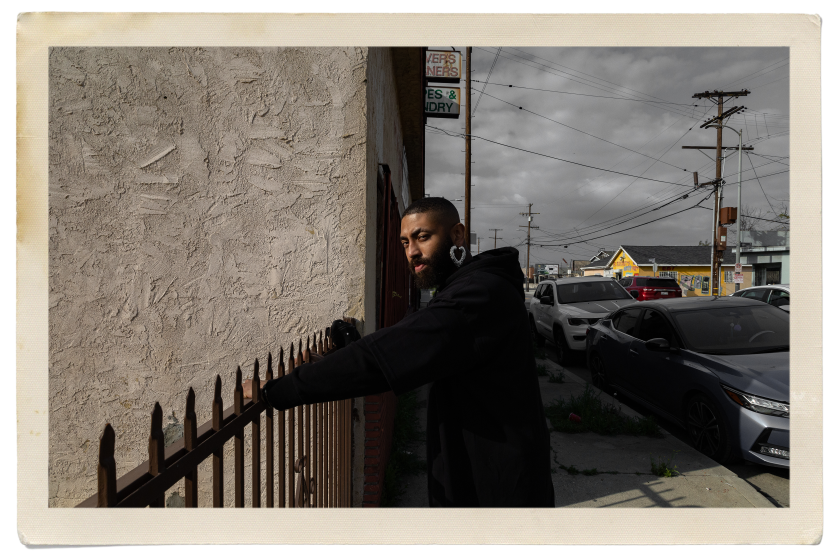

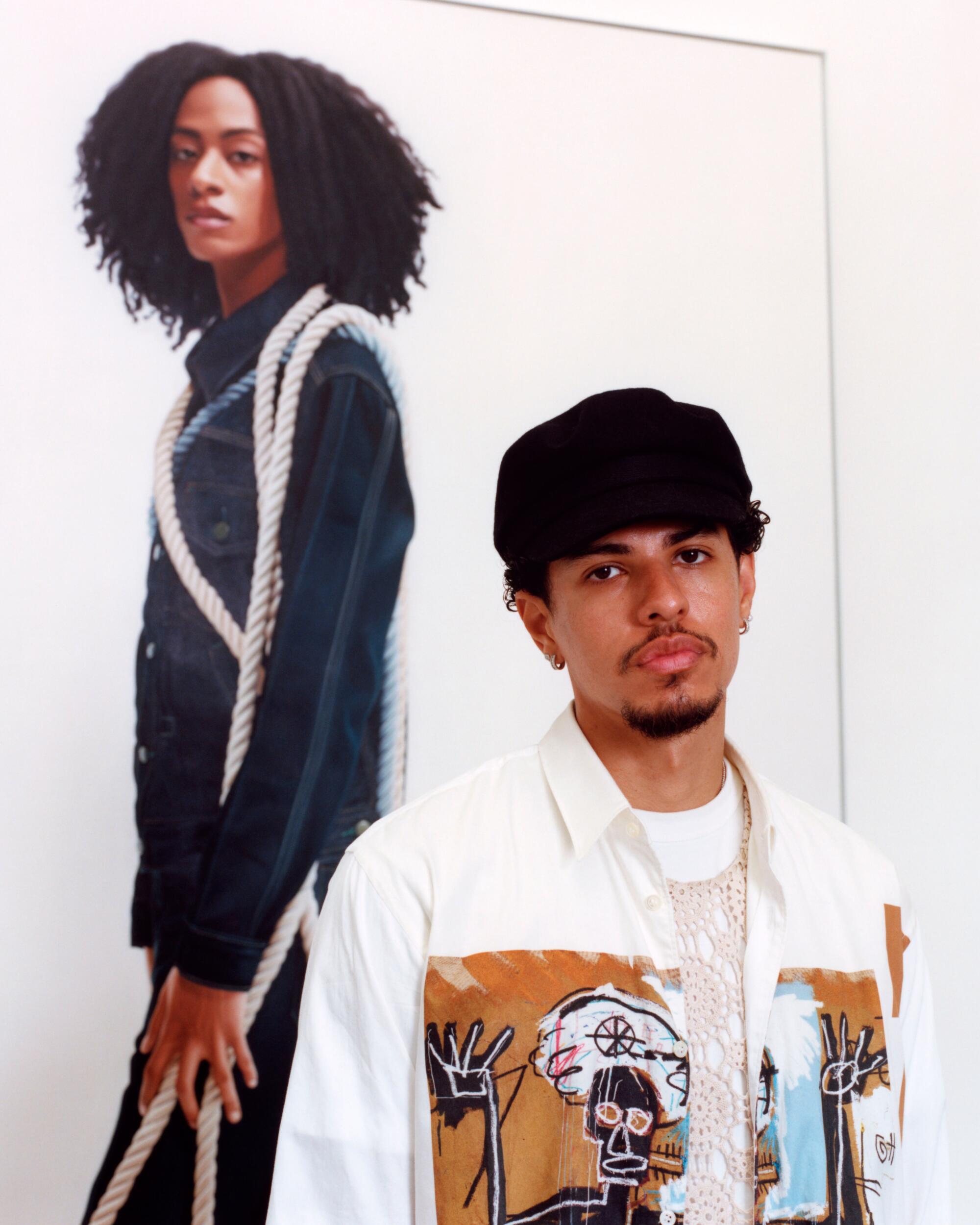

“There’s no bad without the good, and there’s no good without the bad,” artist Delfin Finley explains. We meet on an overcast morning near the Hollywood area, sipping kombuchas while discussing artists who explore the gray areas of living, where joy and pain collide. Finley, who paints hyperrealist figurative paintings that depict his family and friends, follows a similar impulse when bringing his portraits to life. For him, the technical aspects of his craft are a means toward the emotional resonances. How can the movement of oils conjure the aura and history of a person, in all their contradictions and idiosyncrasies? These are some of the questions that animate Finley’s practice.

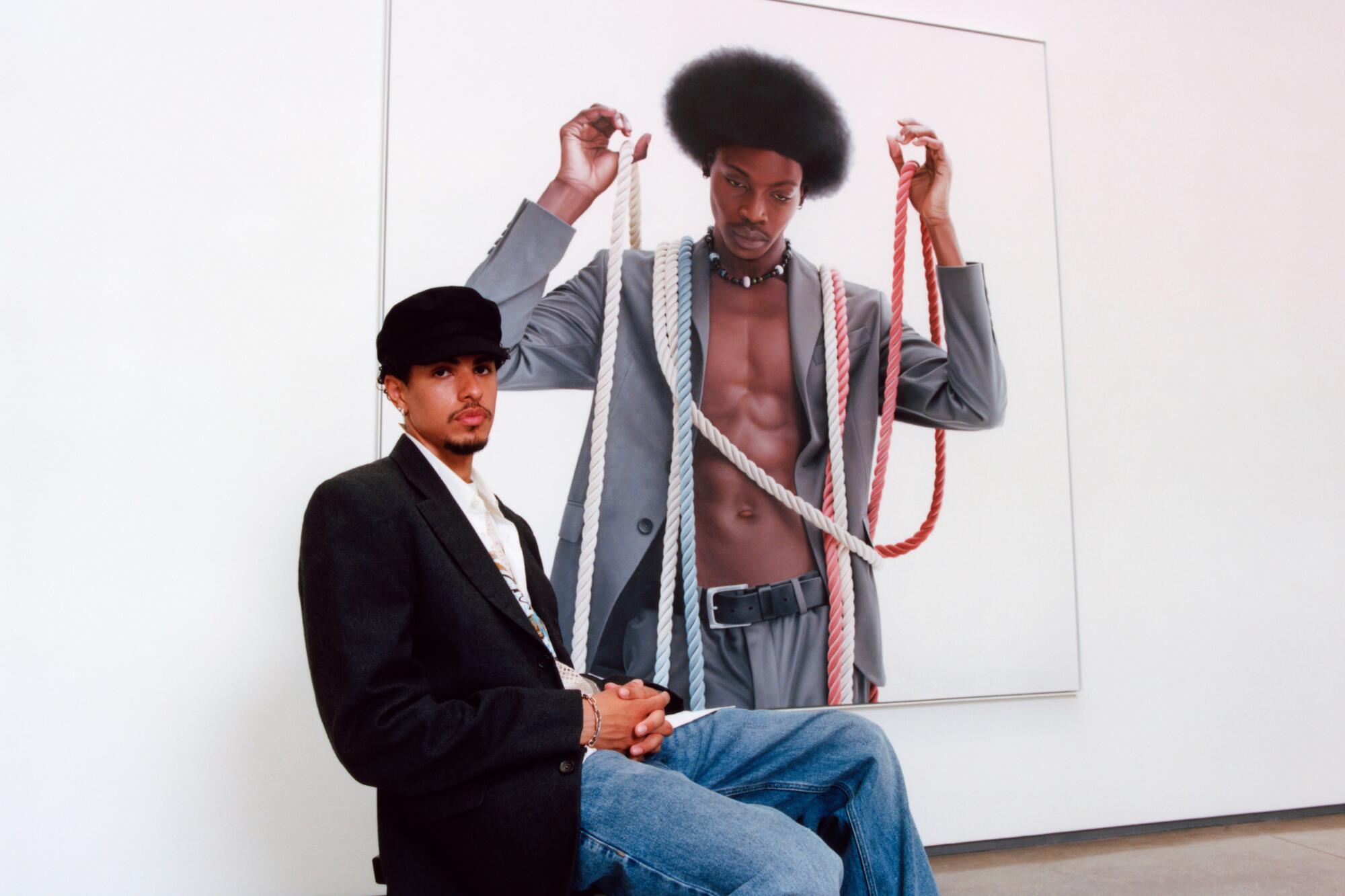

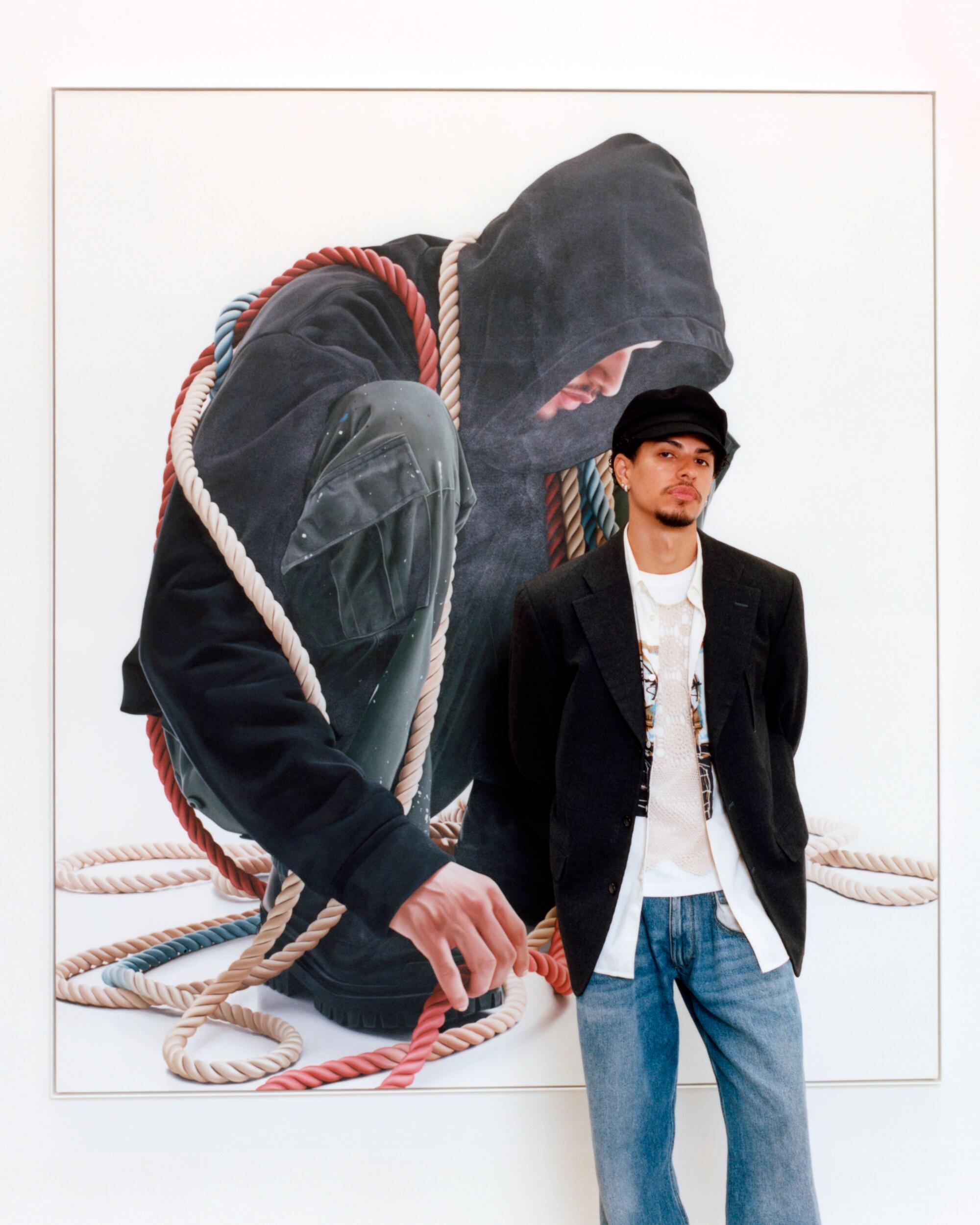

The portraits in “Coalescence,” his new solo exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery, depict super-sized figures set against stark white backgrounds. Measuring between 8 and 5 feet tall, each subject wrestles with an assortment of blue, red and white ropes. In “Mantellum” (2023), a woman stands with her back toward us, her face out of view. Ropes dandle like a makeshift cape against her back. “Regalia” (2022) shows a woman dressed in denim and white Chuck Taylor sneakers, as ropes wrap around her like a dress. Her face meets your gaze, a steady look that gathers like a quiet storm. What stands out about Finley’s paintings, besides the scale, is the presence of his figures. It feels like they are there in the gallery with you, infusing the space with their particular personalities.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Finley is attracted to the mysteries of the human figure. As a young child he drew in notebooks, inspired by the muralists and graffiti artists he would see in South Central. By the time he graduated high school, he transferred his love of graffiti into a painting practice. When honing his craft at Santa Monica College and the ArtCenter, he developed a deeper appreciation for the grandeur of artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and John Singer Sargent. He was touched by their tactile qualities but felt a disconnect due to their focus on white subjects. That tension led him to embark on his own journey into oil and portraiture, which led to paintings of his creative community, including Tyler, the Creator, and Earl Sweatshirt.

“Coalescence” charts a new direction in Finley’s practice. To his interest in figuration, he adds a rope motif, an idea he has been exploring in works that appeared in group shows like “Shattered Glass” at Jeffrey Deitch gallery in 2021. For Finley, the ropes offer a way to think through the pleasures and traumas experienced by Black and brown people in the U.S. The motif becomes a means to interact with history and our connection to it. The ropes are a malleable form, one that shifts according to our own movements. Our past doesn’t hang over us, it’s woven into our very being.

Allison Noelle Conner: You grew up in South Central. How did that neighborhood impact your artist vision?

Delfin Finley: South Central had a big impact on me. Even the concentration of graffiti, just seeing that all over the walls and all over the streets, really stuck with me. It was really interesting to me, this idea of people putting their life on the line to get their message out. That’s really beautiful to me, [that drive] to make art at whatever the cost. Plus, there’s a perseverance this city has. It’s a really tight-knit community.

ANC: Your parents are artists too, right?

DF: Yes, they’re both fashion designers. I think seeing what they were doing up close had a huge influence on me. Even if I didn’t know it at the time. To be able to see the whole process — from the ideation to the sketches to the patterns, to the sourcing of material, to finalization of the product — just seeing what it takes to make something has stayed with me. Those are all pivotal experiences for what I do today.

The independent curator and arts educator has had a nonstop month. He shares how he’s been staying grounded through it all.

ANC: You went from admiring graffiti to doing it yourself. How did that happen?

DF: It was a slow transition. I would do little sketches and do my drawings, but I never had the courage to go out and do it until I was in middle school and met other kids that were into it. We built a community around our shared interests — that’s how we spent our time together. I wouldn’t trade those experiences for anything. It goes back to the execution thing — you do your sketch in your little black book, and when you go out, you try your best to duplicate what you planned. Once you get to the wall, if it’s not quite there, you try it again. It’s a never-ending process, and the closer you get to your expected execution, the higher your standards get. So it’s a constant search for validation within yourself.

But [graffiti] is also very community-based. Your friends are like, “Yo, I saw you up,” and that’s fulfilling. It’s not necessarily for any and everyone. That’s not what it’s about, you know?

ANC: You also studied painting at Santa Monica College and ArtCenter. Could you talk about that transition?

The L.A. multi-disciplinary artist’s practice is about intersections — both literal and figurative.

DF: When I graduated high school, I was pretty much doing a bunch of graffiti. I didn’t have a plan in mind. My older brother Kohshin was going to Otis College of Art, and he had started painting. I was looking at the stuff he was doing like, “Wow, that looks pretty cool.” So I went to Santa Monica College and took a painting course. I really enjoyed it; it was an acrylic painting class. Then I took an oil painting class, and I was like, we might have something here. I ended up taking all the painting courses at SMC and ended up getting a scholarship to the ArtCenter. I wanted to hone my craft. And I met great instructors that I am still friends with today. I can still pick their brains, which is great.

ANC: Why were you drawn to oil over acrylic?

DF: For me, when I’ve gone to the museums, I’ve always been interested in the paintings that are more life-like. The paintings that Vermeer was doing, that Caravaggio was doing. I was so amazed by the technicality of their paintings. But there was a block there in terms of the subject matter. I didn’t see anyone that looked like me or my family, or anyone around me. But the technical aspects of the painting drew me in. When I thought about painting, I wanted to investigate how that’s even possible. How are they even able to achieve that? I wanted to almost replicate that myself, and put my own angle on it, my own twist on it.

Also, acrylic, for me, dried too fast. Oil paint stays wet way, way longer. So you’re able to get the blends and you’re able to render in a way that is much harder in acrylic. When I touched it, it was just a good fit. There’s an intuitive connection.

ANC: Could you talk more about your interest in portraiture?

DF: I wanted to give my family, my community something to see. I think they deserved to be depicted like that. There’s so much time and care invested in [portraiture]. You’re studying their features, you’re really spending hours and hours with someone. I think there’s an unspoken, inherent respect that you have to have for somebody to even do that.

People are always like, “Why not do landscapes? Why not do still lifes?” I think we as humans are the most interesting thing. I am not done with us. People are always trying to move to the next thing, and I’m like, “There’s so much here, though.” I think we’re so interesting. There’s so much nuance and feelings that can come out in an image. There’s so much to behold and to see and to feel.

ANC: At first glance, your portraits could be mistaken for photos. How do you see the connection between photography and painting in your work?

DF: I love photography. But for me, I think there’s a disconnect. It’s a freeze frame. You can’t go there. Photography feels like a time capsule that I can’t open. But with painting, there’s an immediacy to it. I can see the exact stroke that was made, and it’s right in front of me. The painting could have been done last year, the painting could have been done 500 years ago, but that stroke, as it was made then, is right in front of me. I’m seeing it this second. For me, that makes painting eternal. It’s very present. Whereas photography feels like a past moment. With painting, if I wanted to, I could touch it. The painting is right here.

Honesty is what makes the L.A.-based artist’s multifaceted works felt: “If I paint something and it makes me sad, it’s f—ing sad. That is the barometer of the life of the piece, so to speak.”

ANC: Let’s talk about your solo show, “Coalescence.” Where did the idea of the rope motif come from?

DF: In my [first solo] show, “Some Things Never Change” [at Lora Schlesinger Gallery in 2017], there was a larger painting of me, and it depicted me sitting with a noose hanging above my head. The noose represented our history, everything we’ve been through, and how that history is still hanging over our heads to this present day. But I was looking at that painting and thought, “It’s not necessarily hanging over our heads.” It’s not dangling above us. It’s on us. And we have to carry it. We have to bring it wherever we go. We’re born with it. Some days the ropes might feel tighter, and other times, they’re looser. That was the springboard into this series.

ANC: How did you land on the title for the show?

DF: “Coalescence” embodies everything that I’m trying to talk about. It literally means the merging or the joining of multiple elements to become one. And when I think about that, that’s rope. There are literally multiple strands of twine coming together to make one thing that we call rope. But we do that as people too. We’re all very much individuals; we all have our own unique nuances that make us ourselves. But when we come together and talk about our experiences, we realize how connected we are. Even the people that live before us, the people we’ve never met, we are very much a product of their experiences and their decisions.

ANC: What’s your process with your subjects?

DF: Everyone in the paintings are people that are in my life. They’re all friends and family. The process begins with a conversation. We’re talking about their thoughts on all the themes that the paintings are about and how they feel about it. I take some photos, and then when I’m reviewing photos, I try to pick the photo that best evokes the feelings or best represents the ideas I’m trying to get across.

Sometimes there isn’t a perfect image. Let’s say I really liked the head positioning on this one, but in this other photo that we took, I really like where the hands are. I’ll make a composite. So it’s not even an image that existed. People will suggest that I just present the photographs, but this photograph doesn’t exist. The painting itself is a whole new thing.

ANC: And everyone had to stand with the ropes during your photo sessions?

DF: Yes, they’re literally wearing the ropes that we’re seeing. And they’re heavy. I think that their thought process about the whole thing, and the weight of the ropes, shows in the paintings. They’re all carrying the ropes, and they all carry the same history, but every person has a different reaction to it. There’s not one way to react to something. I think there’s beauty in that. The Black experience isn’t a monolith, and connections can be found within our differences.

ANC: What do you want people to get out of this show?

DF: There is a lot of adoration that I have for my community, and I want that to be very evident. I want you to be able to feel that [adoration] when you’re looking at the work. And you know, as much as the paintings are portraits of my loved ones, in the same way, they’re portraits of me. We’re very much a product of everyone around us. Everyone is very connected. I think the same rings true for the artist and the subject. Paintings are almost like a mirror in that way.

Allison Noelle Conner is an arts and culture writer based in Los Angeles. Her writing has appeared in Artsy, Carla, East of Borneo, Hyperallergic, KCET Artbound and elsewhere. Currently, she is the editorial fellow at X-tra Contemporary Art Journal.