This story is part of āCorpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser,ā a special collaboration between rafa esparza, Image magazine and Commonwealth and Council. See how the whole project came to be here.

When I think about my art practice, I like to think of it as a practice thatās cartographical, in the sense that itās charted ā like how I experienced growing up in Los Angeles as a brown, queer first-generation person coming from a working-class family. All those intersections are very important.

My work has always been responsive to my body and to spaces, from institutional to public ones. Performance was always this immediate vehicle where I could do that ā where I could show up in an alley and create something thatās responsive. I also grew up commuting on the public transportation system. Millions of people use it, and I feel like riding on the bus and knowing Los Angeles in that way has allowed me to have a particular experience of the city. All those things have informed how my practice has evolved, not just a creative experience that evolves in a solitary space in the studio. Itās very much immersed in the movement of people in public space.

Iāve always been in love with the lowrider car as a machine, but also as a work of art. When I think about where our art forms reside, outside of the conventions of art, murals are one place, fashion is another, but the lowrider car was always such an outstanding exception because it can exist anywhere. A car isnāt stationary. Because I grew up around it, with my family building cars, it was such a ubiquitous theme, and for the kids in my family, all men, getting a car that they could customize was a coming-of-age thing. It was never, āWeāre gonna go to the dealer and shop for the newest car.ā It was like, āWeāre gonna get a cheap Cutlass or Regal or an Impalaā ā it was a project car; it would eventually be transformed into a car of their dreams.

When I was thinking about performance, about where art exists and how it exists, lowrider car culture was always kind of there, but the proximities were a little bit awkward for me; I grew up around it, but I never saw a feminine or queer expression within those spaces. Women were obviously present, queer people were obviously present, but they had a very different relationship to the cars than men did. You start to see women building their own cars now, but back then, the only times that you saw a woman in relationship to lowrider cars was modeling on the hood or the trunk.

So I wanted to tease some of those conflicting feelings that I had with lowrider car culture. I still have very vivid memories of cruising on Whittier Boulevard with my brother and my cousins and just how unruly cruising was. There werenāt any permits. They were loud because everyone had insane car systems. Constantly being policed ā I mean, there were masses of cars that just took over the boulevard for miles, and the only ways that police could control it was to either show up with massive amounts of officers in riot gear or, usually, they would block off all of the streets that people would use to turn around and go out for another loop, until it extended out to a freeway, like maybe the 605.

I was thinking about cruising specifically, and then, obviously, just saying the word ācruisingā and what it connotes for me ā how that word lives in my body. I came of age to my sexualities by cruising at Elysian Park ā that was the first time that I had a consensual sexual encounter with another man; it was in a public space, in a park ā a park that happened to also have a history of hosting lowrider car events.

Elysian Park has such a complex history, a history of displacement; thereās a shooting range for the police academy; and then these histories of cruising. For a while, lowrider car cruising kind of stopped happening throughout the city, but itās started to come back ā at Elysian Park now, on the weekends, youāll see a lot of lowrider car shows happening again. But the gay cruising has always been present.

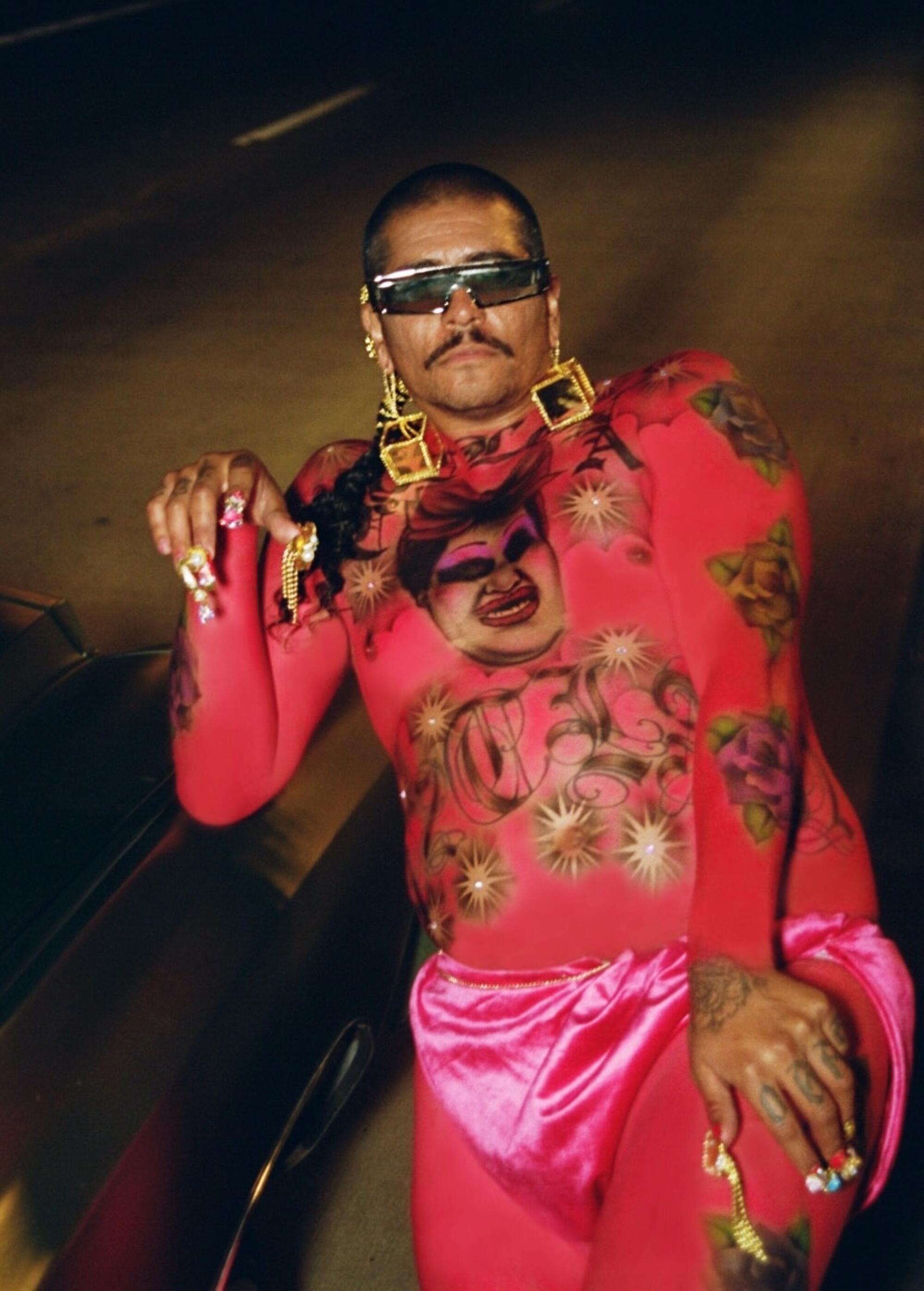

In 2018, I had this idea of collaborating with friends to help me become a lowrider car. I asked Mario Ayala to treat my body like a car and just paint me. We were in conversation about it, but he kind of took the liberty of painting whatever he wanted. I think the only request that I had was to paint a portrait of Cyclona on my chest.

Lowrider cars have so many functions ā sometimes they function as altars; people paint portraits of loved ones that have passed away. Mario had told me he was inspired by the Gypsy Rose, which is coined to be the first lowrider car, and it happened to come out of East L.A. So I wanted to pay homage Cyclona, who is coined for being the first drag queen in East L.A. but also an influential artist who inspired a lot of performance in East L.A., ASCO being one of those.

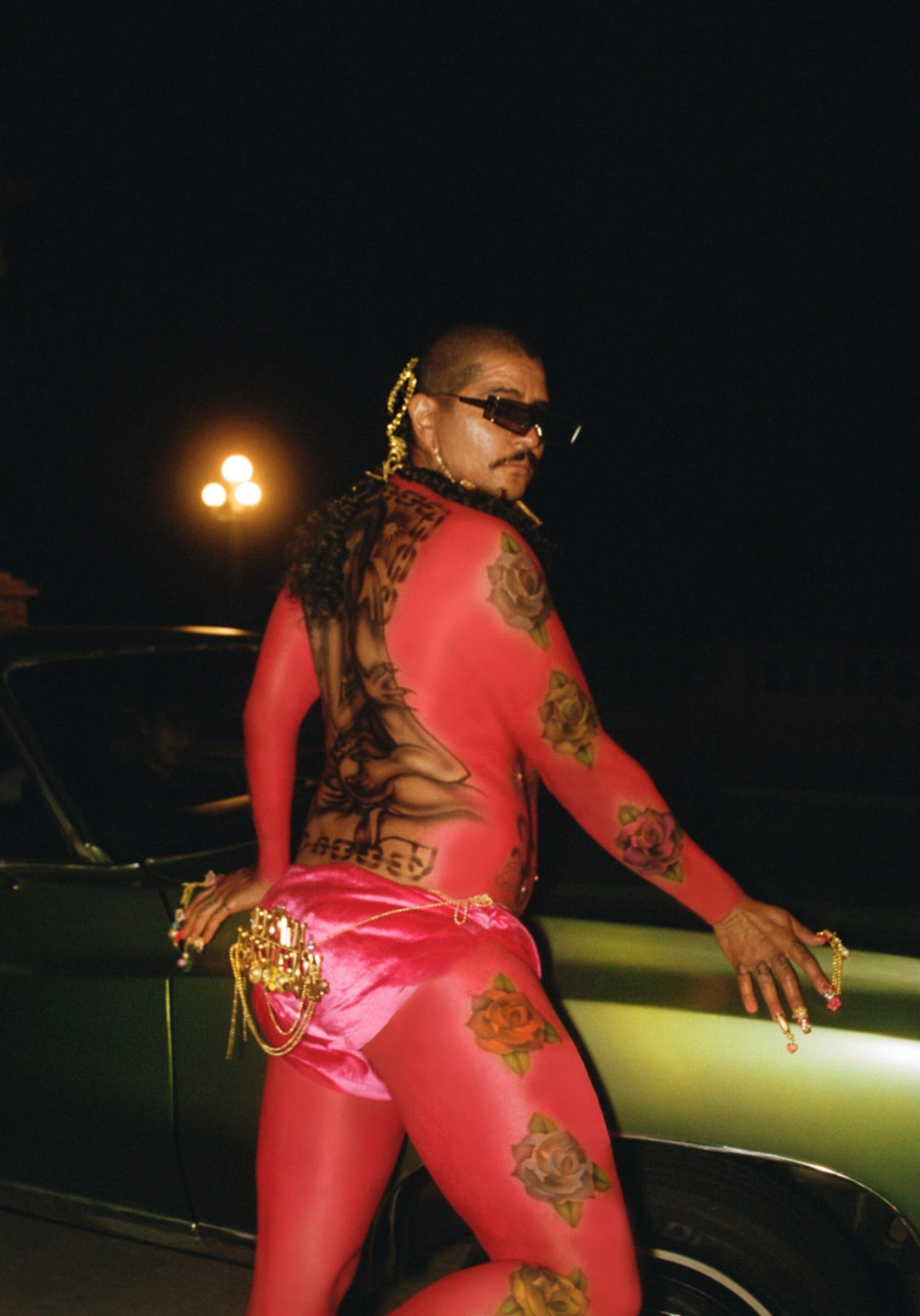

He painted my body this fuchsia pink from head to toe; he painted this homoerotic image on my back, Cyclona on the front; and then my arms were lined with roses similar to the ones youād find on the Gypsy Rose car. Tanya Melendez, this incredible sculptor and hairdresser, made these beautiful nails that she put on me and a plaque that read, āBrown persuasionā ā if you have a car and youāre in a lowrider car club, you usually have a plaque that identifies what car club youāre in. So she made me a beautiful golden plaque that I hung on my butt.

I wanted to create a document of what it entails to transform a body into a lowrider car. Because I remember being around my cousins and family members building their own cars and how I used to geek out on the process ā them sanding the cars, getting things plated, aesthetic decisions regarding the design of the interiors, the plaques. I wanted to create a document that could chart what that process would be like for me transforming into a lowrider car.

The idea was to go to these different places that were historic sites of lowrider car cruising in Los Angeles and that were gay cruising spots in the city. The paint job took 12 hours, and we ran out of light. Mario lives down the street from Elysian Park, the perfect place, right at the intersection of these two worlds.

Iād love to, in the future, make lowrider body suits for friends that are inspired by what kinds of cars they want to be ā everything that a bespoke suit or tailored dress has, everything that entails making something like that, but instead a lowrider armor. This work that Iāve made for Art Basel Miami, called āCorpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser,ā is my first step into that endeavor ā transforming myself into one that can actually be ridden by people.

Iāve been thinking about this piece and working on it slowly. I bought a mechanical horse earlier this year without having any show or opportunity to showcase the work. But I think, for me, this year marks a return of performance after not having performed since the beginning of the pandemic.

Lowrider or just car culture in Los Angeles ā whenever I see it in writing or as a descriptor of Los Angeles, it always kind of makes me upset. Thereās so much in Los Angeles thatās happening, and writers ā especially writers in New York ā whenever theyāre writing about art in Los Angeles, they never forget to mention a car drive to the gallery or to the museum. I wanted to lean into it ā OK, yes, Los Angeles is a city where a lot of people are commuting from different neighborhoods to their jobs and back. But I was thinking about that in terms of isolation and what we had just experienced during the pandemic. I was thinking of the isolation that happens when youāre driving among masses of cars all moving in the same direction. Itās a very interesting kind of communal space, because if youāre driving on a long commute, you kind of familiarize yourself with the cars that are around you. And I think that, to some degree, forms a kind of culture in Los Angeles. So I thought that doing a performance about my relation to cars would be a good way to come back into performance.

In terms of what this piece is, itās a hopeful piece for me. Iāve done performances that people would describe as difficult, that entail a physicality ā either itās labor intensive or a kind of vulnerability that involves risk-taking. And I feel like this piece has everything about building a lowrider car thatās exciting, like decisions about how you want your body adorned, how you want this car to look.

You also have to work with people. You have to get some things done to your car, right? If your car has a bunch of rust, and you need to cut something out of it and replace it, you take it to a body shop and they do it for you. Weāve had to do some similar things in the studio. First, I had to reach out to Karla Canseco because Iām barely learning how to weld. Then, weāve had to outsource some things that we donāt have the capacity to do in the studio, like get a cast of our objects into aluminum. So this whole process of building a lowrider is still very intrinsic to what weāre doing now. And then, the intersection of my queerness and this culture is still hyper present. What Iām asking people to do is to ride me ā itāll be my body but transformed into a machine.

Thereās also this idea of what it means to be a cyborg right now. I have been thinking about how to situate this cyborg that Iām building outside of the conventions of a futurity thatās very white, thatās very dependent on technology thatās supposed to enhance a human body. This cyborg is grounded in a history of anthropomorphic images that are more about relating to things. Iām looking at Aztec and Mayan iconography ā people turning into animals, people turning into plants. The ethos behind that is much less about, āHow is this animal going to empower me?ā Or, āHow is becoming fire going to make me stronger?ā Itās more about understanding what these different entities do and what they contribute to the world.

Iām trying to move through this project in a similar way, so that Iām not necessarily becoming superhuman by becoming a machine. Thereās an intention behind what the function of this machine is. In a very literal form, itās to provide joy, curiosity, wonder to the people that ride me. But then also, conceptually and metaphorically, thereās another function that the piece is prompting people to participate in, to think what this machine could potentially do if it were real.

I do want to arrive to a place where Iām working with robotic engineers and making kinetic suits. When I got the little horse kiddie ride earlier this year, I realized itās very similar to the kind of movement that a lowrider car does. I thought, if I use this machine, what would I do with it? I thought of building a lowrider bike or some really cool lowrider machine that people could ride. But the more that I thought about it, I was like, why donāt I just become part of the machine? What would that look like? Also, what would that feel like for me? This is the first time where Iāll be performing with a machine thatās going to be moving my body, where my body is actually restricted by the movement of a machine. And that feels very important in terms of this journey into collaborating with this type of kinetic technology.

There are so many narratives that Iāve dreamt around this project. If this is a lowrider cyborg, how does it relate to other cyborgs? Iāve thought about āRoboCopā and Iām like, āOh my God, would I get along with āRoboCop?āā Obviously no, right? Because cops.

Based off the conventions and what exists in the world in terms of cyborgian narratives, I wanted to contribute something that isnāt reifying those projects. Everything from the song that I chose ā because right now, the horse is playing an old western racing song ā Iām gonna switch that out for āLet Me Rideā by Dr. Dre, which is also not the perfect audio because the writing and the music are coming from a lens, early rap, where thereās a lot of misogyny, thereās homophobia. But Dr. Dre is also doing something really interesting where heās anthropomorphizing himself, and he talks about himself moving through the streets like a car does. That will be projected through speakers that the rider canāt hear. The rider will instead be listening to a text that Iāll be reciting. There will be a plant somewhere on my body, and Iāll be asking the riders to look for it. The audio is situating the rider in a distant future where thereās a scarcity of habitable land. Their mission is to find a place for this plant to be planted in, for it to be responsibly taken care of. So itās kind of a responsibility thatās being embarked on, on the part of the rider.

I want to be especially careful with my body and how Iām choosing it to be consumed. I think allowing for someone to ride it, and how that person is both initiating and kind of ending the piece, and having those people be from my community ā I want to prioritize that in that experience. Itās a small gesture within a world of commodification that prioritizes everyone else ā especially at a fair. Like, who can buy a ticket to get into the fair? Theyāre expensive tickets. (Itās been really rad that this has evolved into a direction where this piece is going to be free.)

I know that maybe a very small percentage of the people that are going to get the ticket in the mail are gonna actually be in Miami to ride me, but their tickets arenāt going to be given to someone else if we donāt have everyone riding me for every minute of the three hours. Their places are reserved. Thatās a very important thing, to honor the invitation and their presence.

rafa esparza is a multi-disciplinary artist from Los Angeles whose work reveals his interests in history, personal narratives and kinship, his own relationship to colonization and the disrupted genealogies that it produces. Using live performance as his main form of inquiry, esparza employs site-specificity, materiality, memory and what he calls (non)documentation as primary tools to investigate and expose ideologies, power structures and binary forms of identity that establish narratives, history and social environments.