This story is part of L.A. — We. See. You!, the second issue of Image, which explores various ways of seeing the city for what it is. See the full package here.

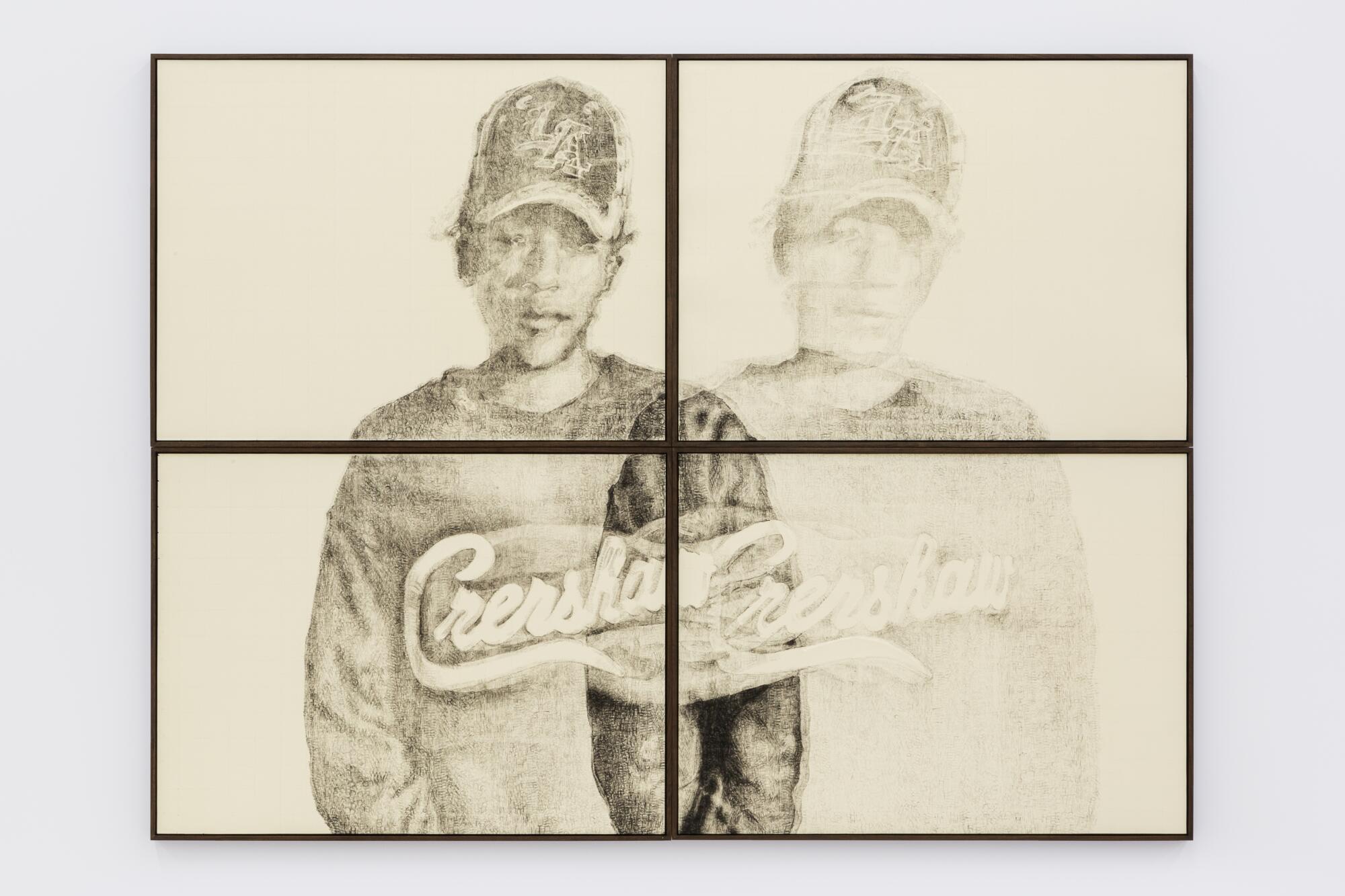

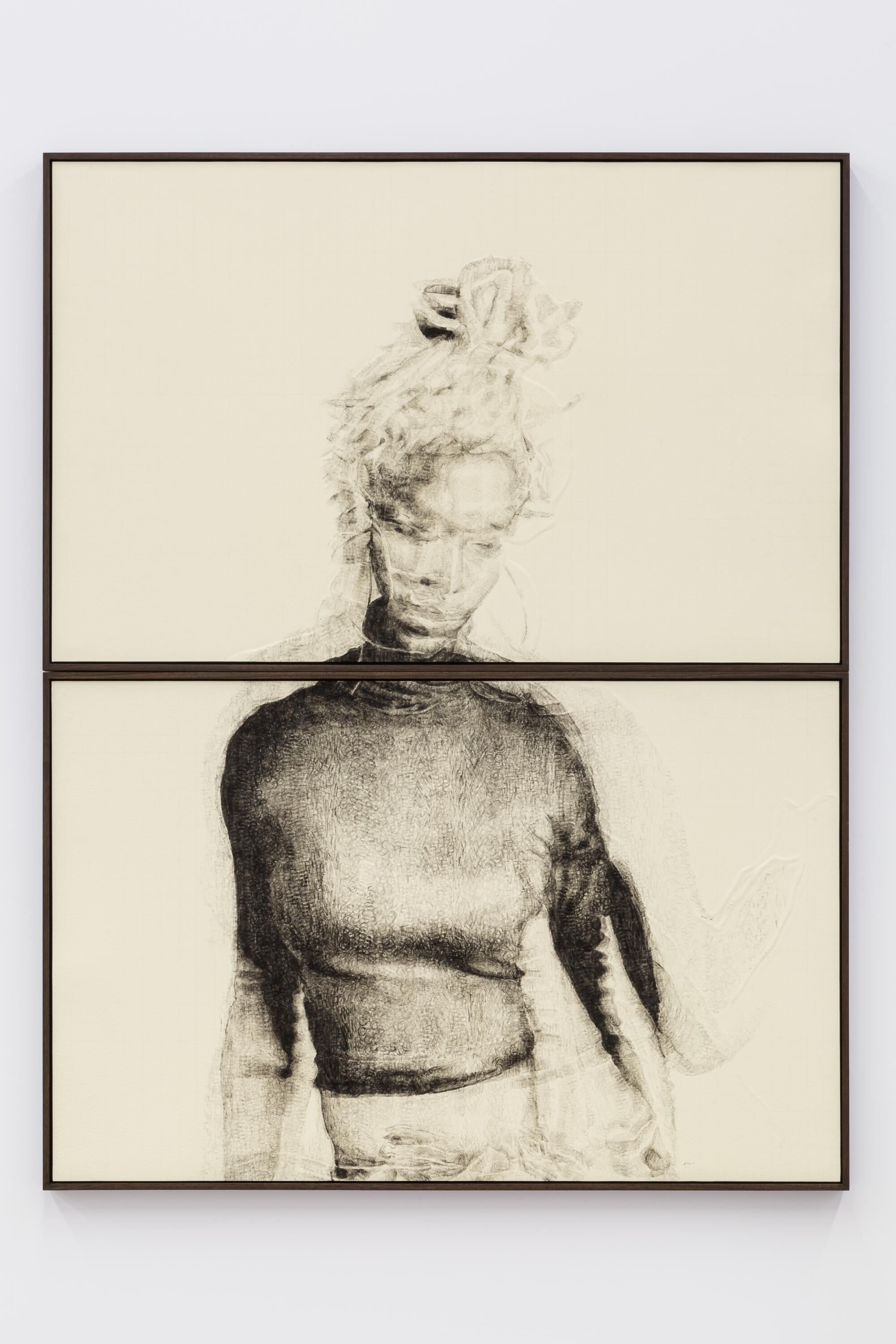

The work of Kenturah Davis is a lesson in seeing. Each encounter with her work reminds you that true sight is a discipline, a practice. You might be drawn into her kinetic, large-scale drawings because her subjects look familiar — that person rockin’ the Crenshaw hat; the woman holding her braids as she dances at the function — but there’s always a standing invitation to stay a while. Her technique — meticulous, patient, layered — demands a sustained gaze.

Recently, I met with Davis in Highland Park, where she lives and works. We talked about the tradition of Black art in L.A., her ongoing exploration of the limitations of language and the diasporic connection between the foothills and South L.A.

Ian F. Blair: I’m very interested in this idea of first impressions. A lot of the way we’re wired now, a lot of the way we encounter people, is through a quick swipe or a quick glance. Where does your desire to hold the gaze, to dive into a person, come from?

Kenturah Davis: I can’t articulate the origins. But I’ve always had this tendency of doing things that require taking your time. Especially now, it seems important. That impulse to do things that take a long time, I think, has then touched on the content in the work about slowing down how we draw conclusions. And that’s kind of like what I’m all about now — slowing down how we draw conclusions. I just try to stay in a space of taking very little for granted and slowing down the way I draw conclusions about things and then making work that is, no pun intended, a slow read.

IFB: Speaking of “slow read” work, let’s talk about this new show that just opened at Jeffrey Deitch in New York. How does this build on the work you’ve created and shown in L.A.?

KD: The Deitch show introduces new work that grew out of some work I did early on in grad school. Thinking about language as a kind of choreography. I went to this lecture by this really amazing performance artist, Aki Sasamoto. She was describing different scenarios that involve thinking about choreography. She was, like, “Architecture can be a form of choreography in the sense that it guides you through a space. Design can be a form of choreography in the sense that a mug with a handle will tell you how to pick it up.” And me being interested in language, I wanted to think about language as a kind of choreography. So initially, I was thinking about laws. Laws are one way we are actually choreographed, like street signs, laws telling us what we can do.

IFB: I’m very intrigued by the signs naming each L.A. neighborhood. I’ve often wondered about whether they are imposing on or in conversation with the history of L.A.

KD: You know, having grown up here — I grew up going to church in South Central when people still called it South Central. And now it’s, like, South L.A.

IFB: Where’d you grow up in L.A.?

KD: I grew up in Altadena.

IFB: How do you feel about the Kelela song?

KD: Oh, I love it. Love. It. I’ll take a shout-out.

IFB: So, Altadena.

More from issue 2 of Image

Darian Symoné Harvin talks to Lauren London about Nipsey Hussle, acting, and how seeking truth is an act of love

We wanted to know about the real L.A. So we asked our favorite Angelenos to show us

Ismail Muhummad meditates on how Noah Purifoy imagined a future where people aren’t discarded

E. Tammy Kim talks to the activists who have the antidote for the erasure of East L.A.

Julissa James profiles the L.A. designer who remade the cobija into luxury fashion

KD: I should say, I grew up on the Black side of Altadena. Symbolically, Lake Avenue, in my mind, kind of represented this divide between the mostly white side and the mostly like, Black and brown side. I lived west of Lake Avenue. But I went to a small, private school that was mostly white, Pasadena Christian School. So there was always this mix. Maybe that’s how I developed my tendency to compartmentalize my experience. Then, I went to school in South Central near where I went to church: Crenshaw Christian Center.

IFB: So many Black people in L.A. worship there.

KD: It’s wild. I grew up with Thundercat. His whole family went there. They all played in the band.

IFB: What was it like to grow up with somebody that talented?

KD: I mean, it was cute. We’re all just kids, you know. The same age. The whole family are musicians — mom, dad, the whole family. His brother Ronald often tours with Kamasi [Washington]. His little brother played with the Internet for a while. They’re all deeply immersed in music. After college, I had went off somewhere. And so I didn’t even know that Stephen [Bruner, a.k.a. Thundercat] became this big musician. Back then, he wasn’t known as well. Thundercat, he…

IFB: You can call him Stephen. It’s OK.

KD: I came back [from school], and he hit me up, because he wanted me to make this coat for him. Because he knew I sewed. He was like, “Yeah, I’m doing music. I’m playing at Coachella,” or whatever.

IFB: Did you do make the coat?

KD: I did. He wore it on “The Apocalypse” album cover.

IFB: When I think of Black L.A., I think about how interconnected it is. Musicians, athletes, Black establishment politicians, Black radicals and organizers, artists — they’re all fused together in a way. What was it like for you coming into consciousness as a Black artist in L.A. as a part of these overlapping traditions?

KD: My mom’s a quiltmaker. She taught me how to sew at a really early age. My dad’s from Kansas. He was a set painter for TV and film. He made façades. He was kind of my initial introduction into thinking that I could be an artist, because he was a kind of artist. He moved here during the ’70s. He met John Outterbridge, Charles White. I don’t know if he met David Hammons. But he met these different people, and he would tell me about them. During that time, it was off and on exposure to what Black artists were doing. I knew some of them, mostly through my dad, not through the education system I was in.

L.A. style trends: The art of Black hair creativity

IFB: What did your dad think about you being a part of the California African American Museum’s 2019 exhibit “Plumb Line: Charles White and the Contemporary”?

KD: He was so proud. Like, so proud. He is so happy for me. Even when I had doubts about how I was going to make it as an artist, both of my parents were the ones who kept encouraging me. I struggled for a bit. There was a moment where I was like, “I’m going to become an urban planner.” Not that I would have ever stopped making art — I would have kept going — but it would have just been something for myself.

IFB: One of the things I loved about that exhibit was that it connected White and his work to younger Black artists. It felt like an intergenerational family of sorts. I was taken aback by that — this feeling of community that exists, particularly among this younger contingent. What have your relationships with artists meant to you?

KD: I think we attract each other. Lauren Halsey is an amazing person. Her partner, Monique, I drew a picture of her, and she’s in the [2019 Matthew Brown Los Angeles] show. I met Noah Davis when he was still alive. EJ Hill. I could go on. I think so much of us are interested in community, and it manifests in different ways. Lauren does so on the ground [through] her organization, Summaeverythang. I work in isolation. Sometimes I don’t see people for very long periods of time. When [Lauren] started providing food for the community last year, I sent money. We’re always ready to support each other, regardless of how much time passes in between when we get to see each other.

IFB: Looking at your work, it has this physicality to it that I’m particularly drawn to. I find myself drawn in by the details, which are meticulous and must have required an incredible amount of patience, exactness, physically intense labor. I’m curious about your process: How does an idea materialize from something you see or feel into something physical?

KD: Oftentimes, the work I make is guided by a particular way of thinking about how we’re using language. Lately, I’ve been thinking through the ways in which language fails us. Sometimes language does not seem to offer us the precise way to deliver a description about what our situation is and the conditions we’re living in.

IFB: Quite often, limitations are self-imposed. I think of the limitations that journalists put on themselves in their descriptions of historical events and people, which comes from their commitment to a vague idea of “objectivity” — which isn’t really grounded in philosophy or the history of thought. Where do you think the limits of language originate?

KD: I guess it depends. I think different things are happening on the macro scale versus the micro scale. On the micro scale, we maybe don’t have the same limitations, because the power dynamic is different on this one-to-one level. On the macro scale, the state and the people who are developing a certain kind of framework have an objective. Like, in terms of race, the objective is to set up these hierarchies that justify a treatment of one group of people by other groups of people. So oftentimes, it comes out of knowing what your objective is in the end, and then you develop the language to facilitate that. That’s what people in power can and have been doing. That’s always mixed in with our ability on the micro scale to push back against that. Even as I’m saying there are limitations with language, it’s flexible enough to keep finding ways to address the limitations and fill in certain voids.

IFB: Thinking through the limitations of language seems particularly important in a place like L.A., where people are spread apart geographically. There’s a lot that remains unknown in a place with so much sprawl. How does the unknown make its way into your work?

KD: I’m interested in perception, how we perceive ourselves in the world around us. I’m pursuing that via thinking about language. Identifying what’s just at the edge of our perception. Like, what’s the limit of my knowledge? I think that’s such a space that’s so generative. I think more people should sit in that space of identifying what’s at the edge of your perception. We often use [language] to categorize things. How someone might think of a person, a stranger — that entirely developed out of the macro language structure that has been imposed on us. When do you think someone is as suspicious versus not? I think the space of acknowledging what’s not known is a space of opening, of having a more open mind about the world, about people and about the conditions of the planet.