This story is part of our issue on Remembrance, a time-traveling journey through the L.A. experience â past, present and future. See the full package here.

I was 18 years old when I first wore a hat in earnest. It was a velvet bowler hat, lined with a golden ribbon with a gentle sparkle. I had just walked out of my college dorm, ready to discover the joys of walking alone through a park on an autumn afternoon. This very adult activity called for a very elegant accessory. Except that, when I dressed the hat, it looked anything but. It felt like a foreign object on my head. On my stroll pedestrians looked at me. I kept my eyes forward. This was not the romantic picture I had envisioned.

When I was a child, I loved hats; the infatuation likely began with Audrey Hepburn movies I watched growing up. I was mesmerized by Holly Golightly wearing her large Chapeau du Matin with a trailing sash in âBreakfast at Tiffanyâsâ and Eliza Doolittle in âMy Fair Lady,â donning the largest hat I had ever seen. My favorite was the musical âFunny Face,â in which Hepburn dances and sings through countless Givenchy outfits and hats. My sister and I emulated Hepburn by trying on my motherâs hats and choreographing performances (my sister did a better job at channeling the actressâ elegance). Each hat â a beret, a bonnet, a cloche â unleashed a different character in us, a new sense of expression; we alternated between goofy and ladylike, trying on personalities that we had seen on screen. Hats made us feel free.

I thought I remembered why I didnât get cast in âGossip Girl.â But the truth was much more complicated.

My fearless childhood spirit gave way to a more controlled and cool disposition during my teenage years. I abandoned the thought of hats â it was too risky to call attention to my self-conscious body that way. It wasnât until I left for college that my mother pulled her hat boxes off the shelves and invited me to look through her collection â a collection I hadnât rummaged through since I was 10 years old. It was then that my mother gave me her parting gift, the velvet bowler hat.

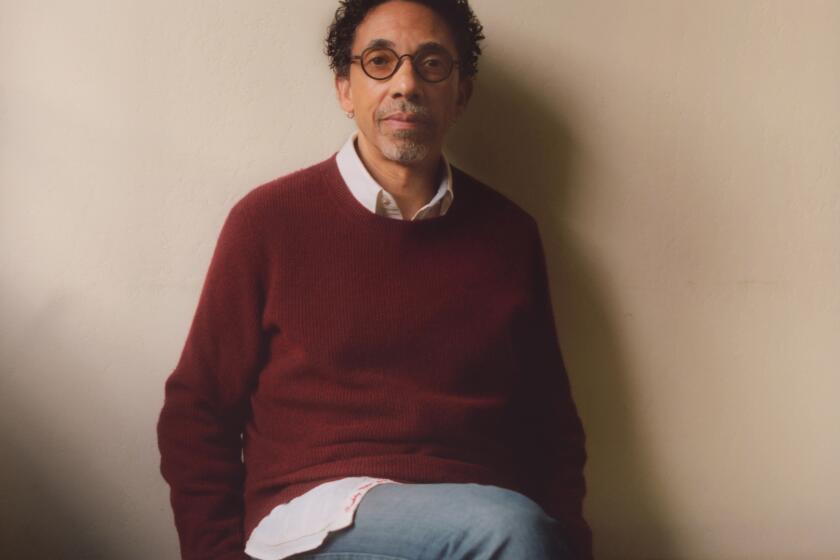

The bowler, it turned out, was designed by legendary Manhattan-based, British milliner Patricia Underwood, also known as âAmericaâs Queen of Hats.â Since the mid-1970s, Underwood has collaborated with esteemed fashion designers, including Oscar de la Renta, Donna Karan, Marc Jacobs, Michael Kors and several others. Her handmade hats have been photographed by Richard Avedon and Annie Leibovitz and made cameos in movies such as âFour Weddings and a Funeralâ and âAustin Powers.â For all the attention they get, they are not especially flashy hats. On the contrary, they are understated, functional yet graceful. Underwood prefers a hat that is comfortably sized with a subtle, fun touch: a red ribbon, a malleable brim. She wants her hats to seamlessly become a part of people, not overwhelm them. In a 2015 Rizzoli book surveying her career, titled âThe Way You Wear Your Hat,â American fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi observes, âA Patricia Underwood hat has a soul.â

A hat, however, does not have the magical property of transferring its majesty to its wearer, as I had hoped on that sad autumn day. Rather, it has to start the other way around. In order to wear a hat, âyou have to have the confidence,â Underwood explained to a reporter in 1988. âBecause people will look at you.â (I lived and learned.) Yet what arrests our attention, what makes a hat worth looking at, she maintains, is âthe inner life of the wearer.â Without that, âa hat is just a âthing on a head.ââ

Hepburn knew how to wear her hats, which is to say, she animated them â through the charge of her eyes, the energy of her walk. âIâm terribly self-conscious about myself, and clothes always give me a great deal of self-confidence,â we hear Hepburn say, to some surprise, in âAudrey,â a new documentary on her life (which has the sexist trap of using a womanâs first name as the title ⌠but I digress). Maybe itâs hard to pinpoint where your confidence originates â in you or your hat, in you or your clothes. Givenchyâs designs are exquisite â âthereâs a purity about his clothes but always with a sense of humor,â Hepburn says â but whatâs captivating is not so much the clothes and hats themselves but the way in which she positively moved in them. It could be the gift of actors â Underwood has said she finds inspiration in actresses like Greta Garbo who wore her hats with drama and charisma. âCock your hats, angles are attitudes,â Frank Sinatra famously advised.

On one merciful day, after I had practiced walking through the park a handful of times, my velvet bowler hat stopped being an alien thing on my head. It helped to unlock a character in me, much as hats did when I was a child â only this time it was the character I wanted to keep. I was no longer hiding under its shadow; on the contrary, it made me feel seen. My footsteps became sturdier, more grounded; my gaze reached farther afield, and I could feel myself slowly carving my place in this world. I came to associate my hat with discovering my independence, my âinner life.â

Underwood designed her bowler hat for women in 1977, at a time when the bowler was only worn by men. Adjusted with a slightly wider brim, her liberated hat didnât care for norms. In just April of last year, during an online talk with the National Arts Club of New York, Underwood looked back on her âfemale-centricâ millinery business and how much of her initial philosophy around hats was influenced by feminist thought. While starting her own practice was hard, she reminded herself why she was pursuing it in the first place: âI was thinking, âWhat is the most important thing about a woman? Itâs her brain. And what is the most important piece of apparel closest to the brain but a hat?ââ For Underwood, hats are much more than adornments; they upliftand dignify women in all their complexity.

Together with my bowler hat, I learned how to walk in my own skin, to feel my own way through avenues and streets. Over the years my hat collection has grown â in quantity and individual size. And if hats are a measure of confidence, then perhaps I went overboard on a trip to Italy when I bought the widest floppy sun hat I could find (I had children pointing fingers at me on the street). Each hat has marked a different phase in my life, a different memory. But I will always hold my bowler hat close.

During these months quarantining at home, Iâve watched my hats steadily collect dust on the tops of my dressers and shelves. Just as many of us feel uninspired to get out of our sweatpants into proper streetwear, popping on a hat, masked and tired, doesnât quite feel right (itâs like covering whatever part of your face that was left). Iâve missed walking out the front door, spontaneously, my hat and me leading the way. The dusty hats signaled that something was stagnant inside of me.

First order of business: I bought a hat box â a ridiculously large one that is bubblegum pink with white polka dots. The box easily accommodates my modest collection. Most importantly, it is keeping my hats protected and ready for wear. Maybe itâs because the hats are in a box now â reminding me of the times that I looked through my motherâs (less outlandish) boxes â but every once in a while, I pull one out and itâs like discovering, all over again, the way hats make me feel free.

Elisa Wouk Almino is a senior editor at Hyperallergic and translation instructor at UCLA Extension.