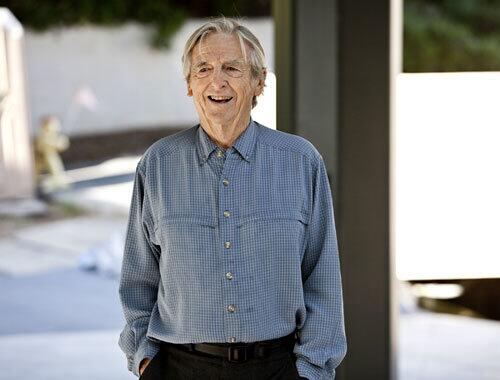

The last living Case Study architect, Beverley Thorne

Beverley Thorne’s biggest distinction very well may be one he’s not so eager to talk about: He is the last surviving architect of the famed Case Study House program. From 1945 to 1966 in his Arts & Architecture magazine, John Entenza published plans for three dozen houses and apartment buildings, all intended to be cutting-edge prototypes for modern living. Among the Midcentury notables chosen for the program: Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, Pierre Koenig, Craig Ellwood and, in later years, Thorne. At 85, the architect is still busy -- designing homes, including a 4,000-square-foot octagonal epic scheduled to be completed in the Bay Area next year after more than a decade of planning and tweaking. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

Thorne recently flew with his fiancée from his home in Kona on the Big Island of

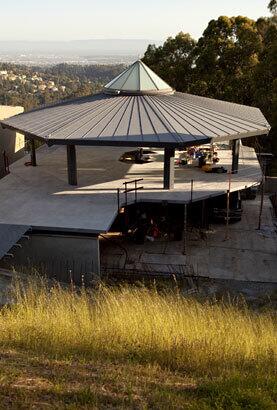

Millennium house gets its name from the fact that Thorne’s initial designs date to 2000. “It had to be engineered that way to hold up the reinforced concrete floors,” Thorne says, adding that his client wanted to park his 1957 Porsche Speedster in the living room. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

Thorne sweeps the concrete of Millennium house as client Edward Baker looks on. Thorne estimated that he has designed upward of 200 houses in a career spanning more than five decades. Most, if not all, are on steep hillsides and are built out of steel, a material the architect fell in love with early on. “Back then, a wooden beam was only 24 feet long, where its steel counterpart could be 60 feet, even longer with proper welding,” he says. “That gave me so much more freedom.”

It was the ingenuity of his frames that allowed Thorne to perch so many light-filled homes securely and airily on steep cliffs. “He likes to celebrate how structures float in gravity,” says Pierluigi Serraino, the author of the book “NorCalMod.” “It was always a heroic gesture.” (Robert Durell / For The Times)

Advertisement

The octagonal roof is topped with a retractable skylight. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

And the retractable skylight is topped with a wind ornament. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

The skylight, viewed from inside. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

Architect Thorne, right, and client Baker look at glass samples for the house under construction. Thorne’s genius remains mostly uncelebrated — in part, a conscious choice. In the mid-1960s, he changed his name to David Thorne and won acclaim for work that included a dynamic Bay Area house for jazz musician

Advertisement

The blue LED glow of a handrail in Millennium house. (Robert Durell / For The Times)

When he’s not on site checking on construction, Thorne works at a small drawing table set up in the screened-in lanai at the front of his Hawaiian home. He’s reluctant to talk about the Case Study program. “Most of those fellows are long gone. It’s kind of spooky that they are,” he says with characteristic understatement, perhaps unaware that with the death of Kemper Nomland Jr. in December, Thorne is the last survivor in a list that contains fewer than three dozen names. At 85, he may move more slowly than in years past, but he still jumps up to receive a call from the contractor on a project he designed in the Big Island. And in an instant, his buoyant smile returns.

Related:

Case Study House No. 22: The story behind L.A.’s original dream home

The best houses of all time in L.A. (Robert Durell / For The Times)