At home among the dead

Manila -- Sometimes on the hottest nights, when the air inside her shanty barely stirs, Mellie Soliman lays her head on the cool, black marble surface of the living-room crypt and finds relief.

Yet the nights are not always restful in this place called Norte. In the quietest hours, spirits emerge. Soliman sees them mostly after midnight, the hour she once found a mother and son standing at her door.

âThe woman was all white,â she said. âShe couldnât talk, but motioned that they were thirsty, so I went to get them water. When I came back, they were gone.â

She explains such apparitions with a near-mystical calm: âThere are some here in Norte who have left us but still do not think they are dead.â

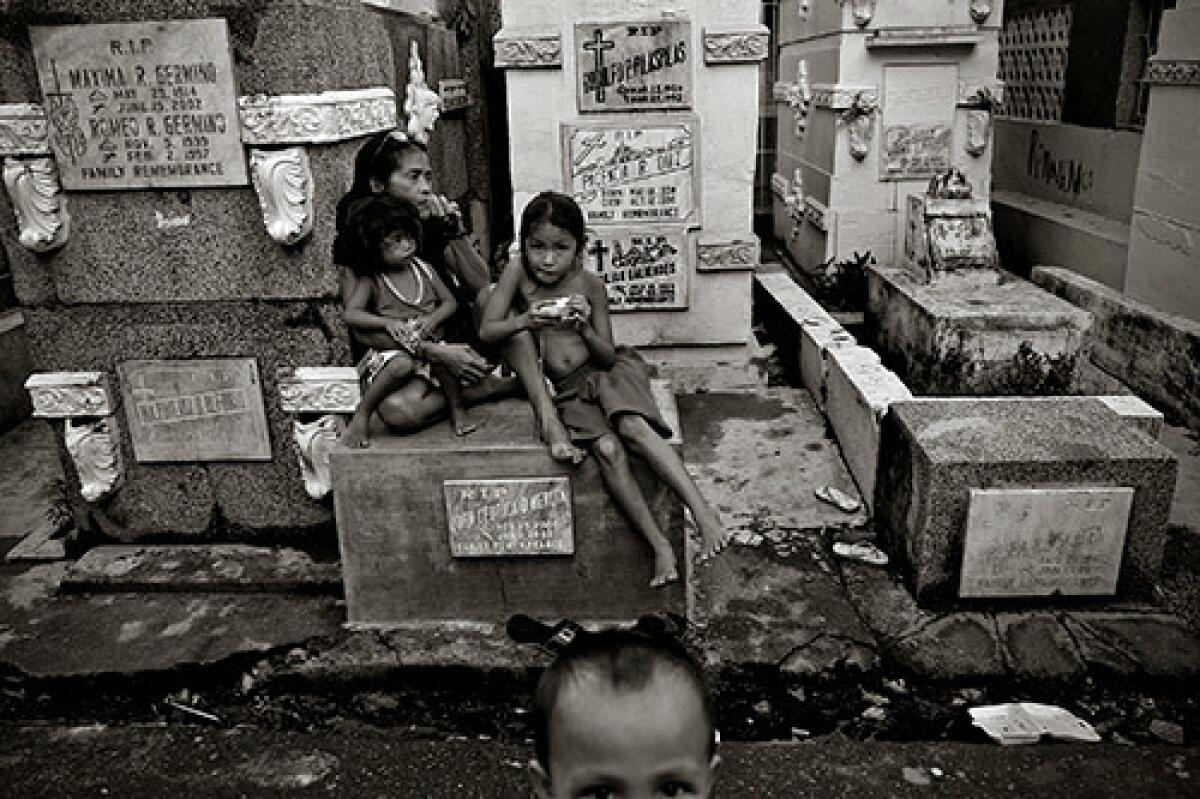

Soliman is familiar with the habits of the deceased. The barefoot grandmother and her extended family are among 50,000 poor but stubborn Filipinos who carve out an unorthodox existence in Norte, or the North Manila Cemetery, which is the countryâs largest public burial ground and a bustling community where the living share space with the dead.

Each day in Norte is marked by life and death. New family members marry in, old ones die off. Often, as many babies are delivered as people are buried. The children are soon taught respect for the departed, and instructed not to play or make noise near the slow-moving funeral processions.

Life is hard: Without plumbing or running water, the narrow streets overflow with foul effluent dumped from buckets. The bootleg electricity lines rigged amid the gravestones are often cut by city officials.

Yet the alternative is worse -- the squalor of itinerant Manila slums such as Tondo. In a metropolitan area where 20% of the 10 million residents are homeless, the most destitute exist atop a sprawling garbage dump in Tondo where crime and disease are rampant.

In Norte, life is safer, and quieter.

âThe dead donât scare me so much,â said Soliman, 62. âItâs the living Iâm afraid of.â

There are few places on Earth where grinding poverty and overcrowding foster such an unlikely life-and-death arrangement.

In Cairoâs 700-year-old City of the Dead, nearly 1 million people live among the ancient tombs. Here on the Philippine archipelago, experts attribute Norteâs large number of residents not only to economic necessity, but to the cultureâs peculiar attitude toward death.

âMany Filipinos donât use the word âdead,â â historian Alejandro Roces said. âRather, theyâre referred to as âthe departed,â the ones who just happened to go ahead of us. For many, theyâre seen as just as alive as you and I.â

Each November, many of the 89 million residents of this largely Roman Catholic country visit cemeteries to observe the religious festivals of All Saintsâ Day and All Soulsâ Day. The two-day event includes music and socializing, bringing a festive atmosphere to grounds usually associated with an eerie quiet and calm.

But many disapprove of the living tomb-dwellers. Come campaign season, some Manila politicians repeat the promise to âclean up Norte,â which some view as a national disgrace.

âItâs not right,â city housing officer Deogracias Tablan said. âThese people have been tolerated. But this is a sacred place for the dead that has been taken over by the living. Shouldnât the deceased be allowed to rest in peace?â

Manila newspaper columnist Adrian Cristobal dismisses such government complaints.

âItâs a solution for the destitute,â he said of Norte. âAnd they may be poor, but these people are all voters. The politicians are afraid to touch them.â

Norte resident May Canary insists sheâs not disturbing anyone.

âOur life here is not a sign of disrespect -- itâs just the opposite,â said the 29-year-old mother, who lives three mausoleums down from the Solimans. âWeâre here as caretakers of the tombs. Who else would do this?â

*

Both living and dead have populated Norte since it opened in 1884, historians say. A burial site for the nationâs rich and famous, the cemetery needed paid caretakers to guard the valuables often sealed with the body inside the mausoleums.

Over the decades, Norteâs population swelled. More bodies arrived with more caretakers. The living became tolerated in the realm of the dead.

In recent years, hordes of illegal squatters drifted to the 135-acre cemetery, moving into mausoleums and camping between tombstones. In a nation where the lack of housing is epidemic, officials had little choice but to look the other way.

âThe governmentâs policy is not to allow these people to live here,â Tablan said. âBut realistically, where can we put them? Until we have a solution, weâve decided not to touch them at all. That doesnât mean weâre happy about it.â

Although there are few official records, Hermogenes Soliman says his extended clan of 60 is among the oldest of the graveyard families. Soliman was born in Norte in 1931, and says his parents lived here for years before that.

As a boy, he played among the tombstones. When it was time to take a wife, he brought the reluctant Mellie to his graveyard home.

âAt first I was afraid of the spirits,â she recalled of that moment 25 years ago, leaning against the pink-rimmed marble crypt where seven relatives lie. âBut eventually this place became home.â

The Solimans have worked hard to make life comfortable for their four generations, who live sprinkled across Norte.

In Mellie Solimanâs living space, her husband nailed up a tin roof to keep out the rain. A towering tree sits to one side of the encampment, with a picture of Jesus nailed to the trunk.

In addition to the main crypt, two others sit under the roof. Children sometimes sleep atop the marble edifices. They do their homework there. On social occasions, the family uses the stone slabs as buffet tables.

In an adjoining alley lined with crypts, family chickens run and squawk. Cats sleep lazily atop the stones, until theyâre chased by the Solimansâ playful puppies.

The only thing the family doesnât use the crypt for is a television stand.

âThat,â Mellie Soliman said, âwould be sacrilegious.â

*

Like many residents, the 75-year-old Hermogenes Soliman makes his living from the cemetery as a contractor who supervises work -- including painting, masonry and clearing brush -- on the tombs financed by owner-families.

October is a busy month. Laborers scramble to clean up Norte before visitors arrive for the religious holidays. The streets are swept and scoured, mausoleums painted, the legions of orphaned beggar children chased away.

The traditional gifts that families leave behind at the graves -- cooked meats, apples, oranges and pears -- are scavenged by Norteâs families. In this graveyard ghetto, such precious sustenance cannot go wasted.

Year-round, Norte is a thriving city, teeming with commerce. There are makeshift neighborhood kiosks that sell noodles, rice and cellphone cards. Vendors wander the streets peddling ice cream and bottled soda.

The cemetery has its own taxi fleet: Drivers line up inside the main gate on motorized scooters, waiting to ferry commuters to their jobs as maids and restaurant workers.

Thereâs even a graveyard government. Each sector has a neighborhood chief to impose the law and settle differences between neighbors.

Mellie Soliman says the worst things happen outside Norteâs gates.

Three of her grandsons were killed in recent years working in the Manila slums.

The last was 16, slain by a gang of thieves as he sold flowers to gravesite visitors. Now he is buried in the living-room crypt, where his grandmother says she can keep a better eye on him.

*

Norte has its own tensions. The cemetery is divided by class: Although no one pays rent, jobless squatters who do no work are at the bottom of the heap and are shunned. Established families such as the Solimans command respect.

City Hall workers and policemen also live here.

In one exclusive area, paid caretakers of the gravesite of the family of Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo -- an immense pyramid flanked by marble sphinxes -- enjoy air conditioning, cable television and a washer and dryer.

Many Norte residents say they do not feel poor. Nor do they worry about disease, despite their proximity to so many corpses.

âLook,â said Mellie Solimanâs daughter-in-law, Carmenita, 41, holding her 1-year-old granddaughter. âDo these children look sick to you? In Tondo, this girl would not survive.â

But Mellie Soliman worries. Recently, corrupt cemetery officials tried to make money by reselling burial space. Workers exhumed dozens of graves to make room for more dead, leaving the reeking coffins in the open.

âTo leave those bodies there did not respect the dead or the living,â she said.

Although the cemetery director was fired, the incident has brought new calls to clean up Norte. Officials recently relocated 60 families to a nearby dog cemetery. Thereâs also talk of building a security fence and cutting off power for good.

âI liken these people to frogs, which will adapt to any environment -- even a frying pan,â said Tablan, the city official. âThe trick is to turn up the heat. Then theyâll jump.â

Hermogenes Soliman insists heâs not leaving -- not even after he dies. He pats the large marble crypt, saying it wonât be long before heâll join his ancestors there.

He finds peace in that.

âWhen I go, this is where theyâll put me,â he said. âMy grandchildren will know right where to find me. That way, they can still take care of me.â

Glionna is a Times staff writer.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.