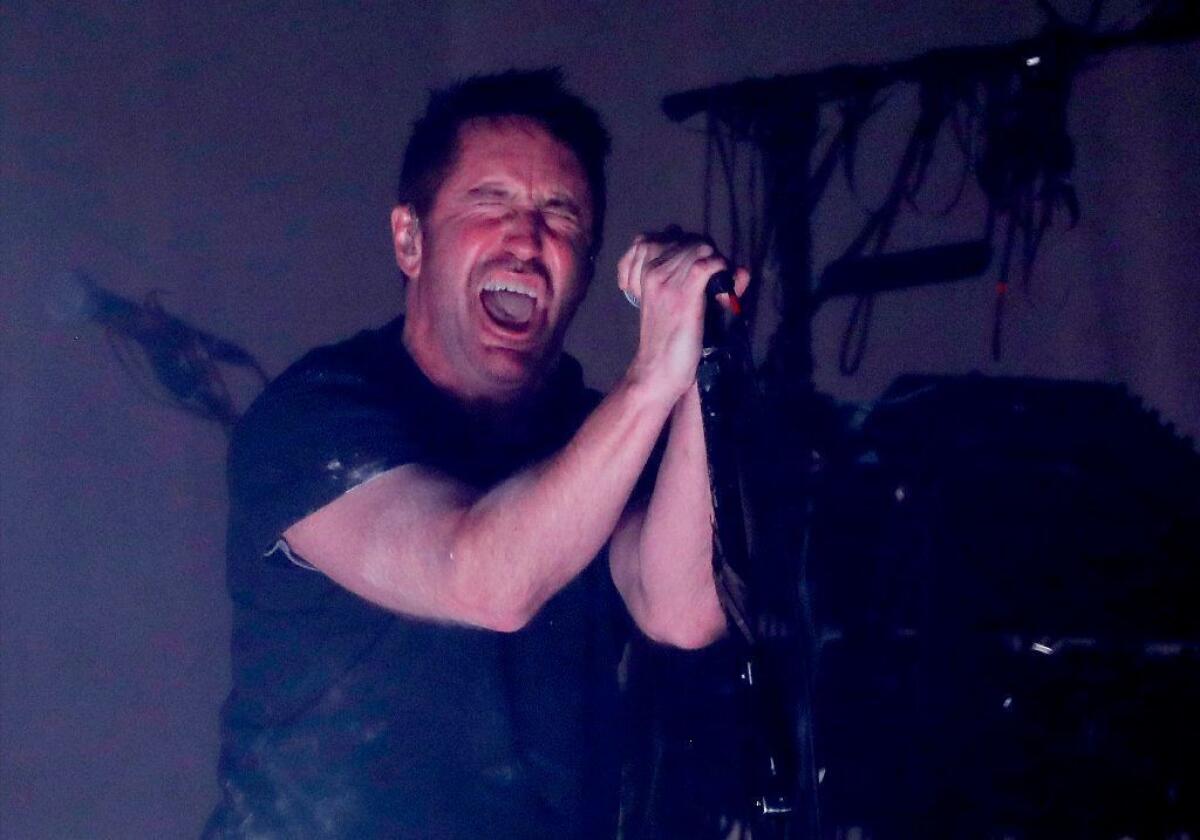

Review: Trent Reznor’s Nine Inch Nails at 30 sounds like a band for right now

Trent Reznor is an Oscar-winning composer and the frontman of one of the most ambitious projects in rock for over three decades. But when Nine Inch Nails walked out onto the Hollywood Palladium stage for the first of their six-night stand on Friday, it felt a bit like a basement punk show.

A very artfully-lit, rigorously-plotted punk show from one of the most accomplished acts in rock, for sure. But kicking off the set with the double-time industrial blast of “Mr. Self Destruct,” from 1994’s “The Downward Spiral,” was a statement. Reznor may have just scored a Ken Burns documentary series, but Nine Inch Nails has’t gone austere at all.

It’s hard to think of another contemporary rock band that, arguably, is hitting its aesthetic peak after initially forming at the end of the Reagan administration. The addition of Atticus Ross, the British composer, multi-instrumentalist and Reznor’s partner in film-score work, into the permanent NIN lineup in 2016 obviously reinvigorated the project.

It would have been easy for Reznor to have actually mothballed the live band when he said he would in 2009, and settled into a life racking up awards in full-time film work. But Reznor’s vision and skills as a producer have always anticipated where music was heading.

The grinding cyber-goth of his early career has come back in vogue (check out the new Grimes single, for starters). And as American culture seethes with anger and anxiety about life in late-techno-capitalism, there’s need for the brutal side of NIN all over again. They delivered it on Friday night.

In June, the band released the short, cutting LP “Bad Witch” after a flurry of EPs highlighting the duo’s more serrated, noisy interests. The band — Reznor, Ross, drummer Ilan Rubin, guitarist Robin Finck and multi-instrumentalist Alessandro Cortini — put the violence of NIN up front on Friday. In a time when musicians from hip-hop to techno are rediscovering distortion and loathing as virtues, the band read the room perfectly. (A warmup set from pioneering Scottish noise-rockers The Jesus and Mary Chain, a huge influence on Reznor, primed the crowd for it.)

The cuts they played from “Bad Witch,” including “S- Mirror” and “God Break Down the Door,” had the trebly churn of ‘80s crust- and post-punk.

When Reznor broke out his saxophone for the latter cut, it was a reminder of how anger and artiness have pushed and pulled throughout his whole career. Sometimes he emphasized more of one or the other, but that tension is what makes NIN so important, then and now.

Reznor completists were likely thrilled at a cameo from the singer Mariqueen Maandig, Reznor’s partner in the band How To Destroy Angels (and his wife). They played a trio of tracks from that band’s catalog, and the foray into more textural beauty and atmosphere was a nice release from all the fury before and after.

But even the now-canonical NIN hits — “Head Like a Hole,” “Reptile,” “Closer” — had a new venom that seemed to speak right to this moment. All the disappointment, confusion and rage of the last couple of years had these old, beloved songs as a backdrop, and they felt vital and invigorating all over again.

Of course, the band closed with “Hurt,” the mournful death ballad that Johnny Cash made his own. It was hard not to read it as a bit of an elegy for the optimism that’s been drained out of America.

But in the hands of this era of NIN, it also felt kind of reassuring. Anger can heal, anger can drive. If you self-destruct, you can still come back even better.

For breaking music news, follow @augustbrown on Twitter.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.