Walter Cronkite: And that’s the way it was

- Share via

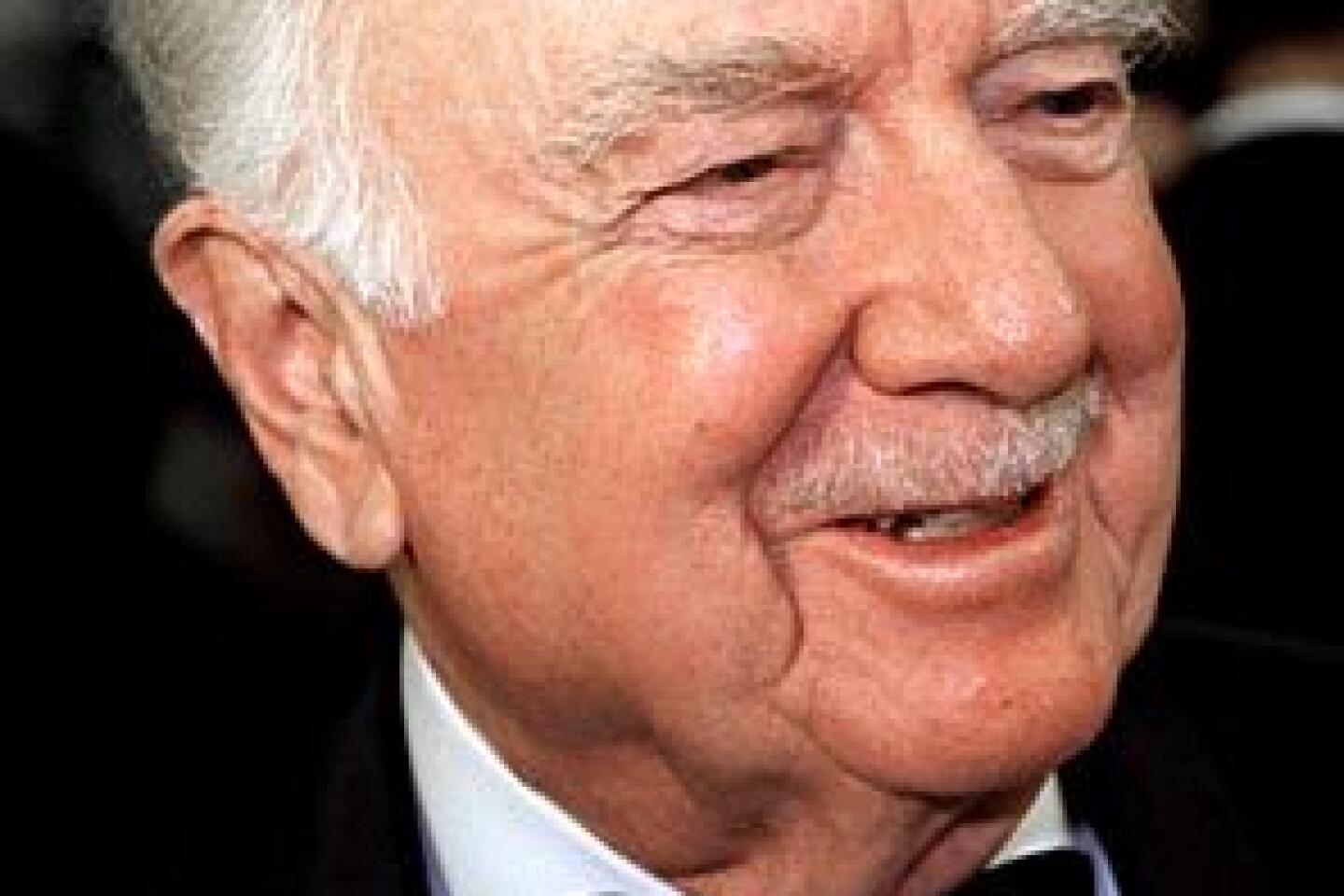

For many who grew up in the 1960s and ‘70s, Walter Cronkite was the voice of unfolding history. On the “CBS Evening News” and on the spot, his eloquent mediation of the great events of an age almost pathologically overflowing with them was essential to the way those events were understood. Even when he was temporarily at a loss for words -- his tears at the death of John F. Kennedy, his inarticulate glee at the moon landing (“Whew, boy!”) -- he somehow spoke for the nation he spoke to.

Cronkite was not just a newsman; he was -- like Edward R. Murrow, who brought him to CBS and television -- as close a thing to the idea of a newsman as his age imagined. Except perhaps for Chet Huntley and David Brinkley, his high-powered NBC competition, all TV news anchors, news readers and news reporters, even the most august of them, seemed like variations on his theme, shadows of his Platonic ideal. A decade after his retirement from the anchor’s chair, he was still being named the most trusted man in network news.

How to account for this? It was more than just intelligence and talent. The news that Cronkite reported was barely distinct from the news his colleague-competitors reported. (And to the extent it was, it was not the source of his regard.) It must have been something more basic to his bearing and manner of being. He was serious, but good-humored; he had a common touch without being folksy; he was impartial but not amoral, disinterested but not detached, above the fray but not without a point of view, though he never made himself the story.

He later expressed regret at his momentary display of emotion reporting the Kennedy assassination as behavior not befitting an anchor, but it was exactly that mix of feeling and restraint that defined him.

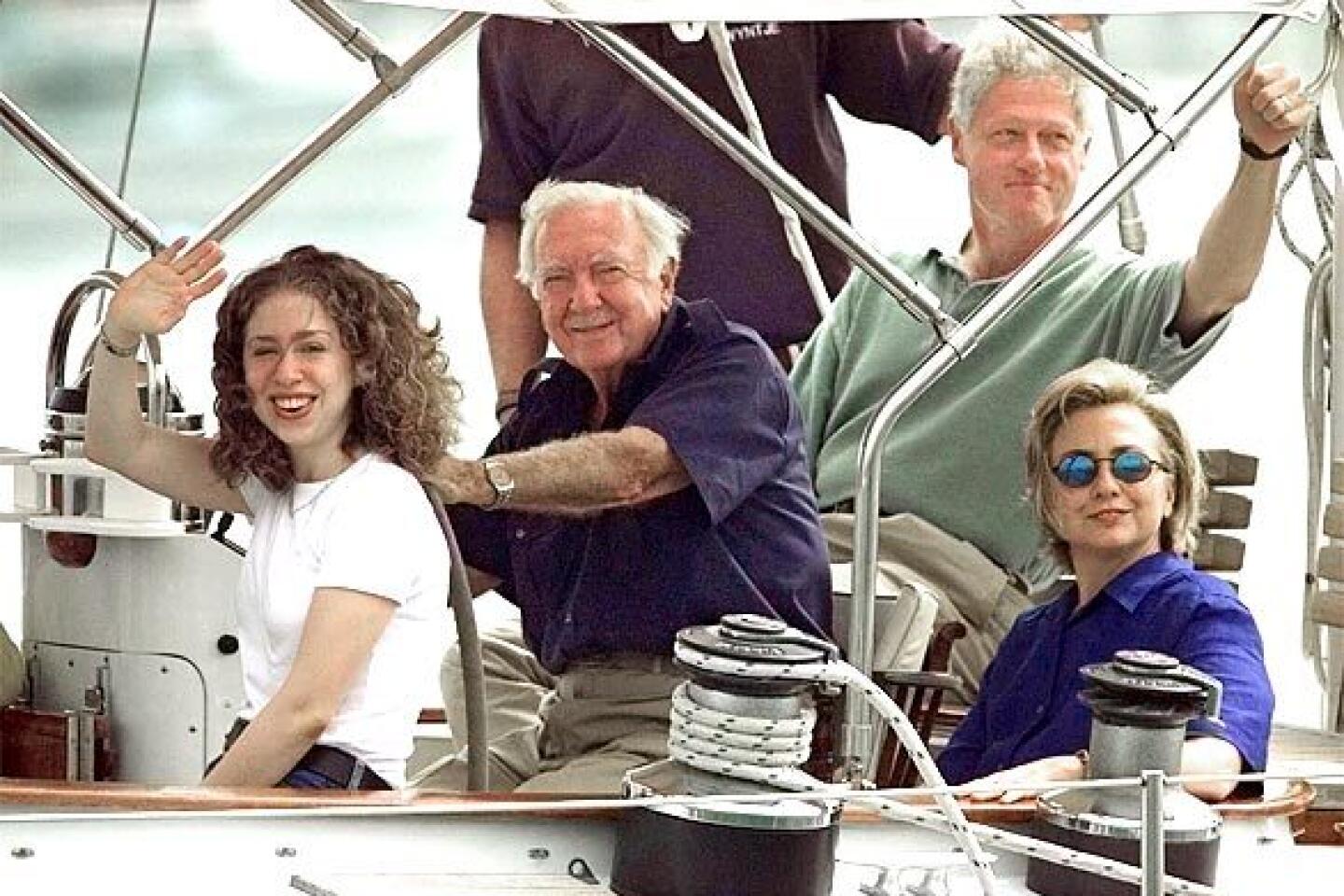

And he was paternal. As a child, I conflated him in my mind with Captain Kangaroo, another graying man with a mustache who ordered the world in a voice of quiet authority, and with that other grand-paternal Uncle Walter, Disney -- men who gave you the feeling that things would be all right, in the near future and the far.

We have come to understand news as show business, and are inclined to consume it as such, as part of the many-channeled entertainment package our broadcasters and cable companies provide, and not as a break from it -- as a sacred space in which facts matter more than opinions, but in which opinions, when rarely and carefully expressed, matter.

When Cronkite spoke, it was with a thoughtfulness that the 24-hour news cycle does not encourage; and when there was no time for reflection, he avoided melodrama, frenzy and guesswork. His reports on the deaths of Lyndon B. Johnson and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. are online to hear, and they are marvelously straightforward, and all the more moving for it. And his famous editorial that Vietnam was most likely not a winnable war came from his own, on-the-ground observations; he went there looking for answers after the Viet Cong’s Tet Offensive made him question the official reports of American military progress and superiority.

The rolling rise and fall of his voice and the rhythms and pauses he built into his prose gave his reporting the subtle weight of blank verse. Cronkite cut his teeth telling stories in print and over the radio; he knew how to make pictures from words. Similarly trained reporters dominated TV news for the medium’s first decades; it was an oratorical era. But as they aged and retired, the networks turned to more telegenic models, to prettier people and -- reasonably enough -- a more visual approach to the news.

Network news anchors still aim for that mix of eloquence and authority that Cronkite embodied, but they compete, at a disadvantage, with the noise of an ascendant punditocracy and the mountain-from-molehill nattering of cable news organizations that live on crises -- it’s not the old voice of reassuring honesty that they cultivate, but one of perpetual anxiety. There are many more rooms in the mansion that is television news nowadays, but they have grown proportionately smaller; they are no longer fit for giants.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.