Ditch the car and the backyard: 5 lessons from 4 L.A. architects about L.A.âs future

Walk through the current exhibit at the Architecture + Design Museum in downtown Los Angeles and you will find some wild visions of a future L.A.

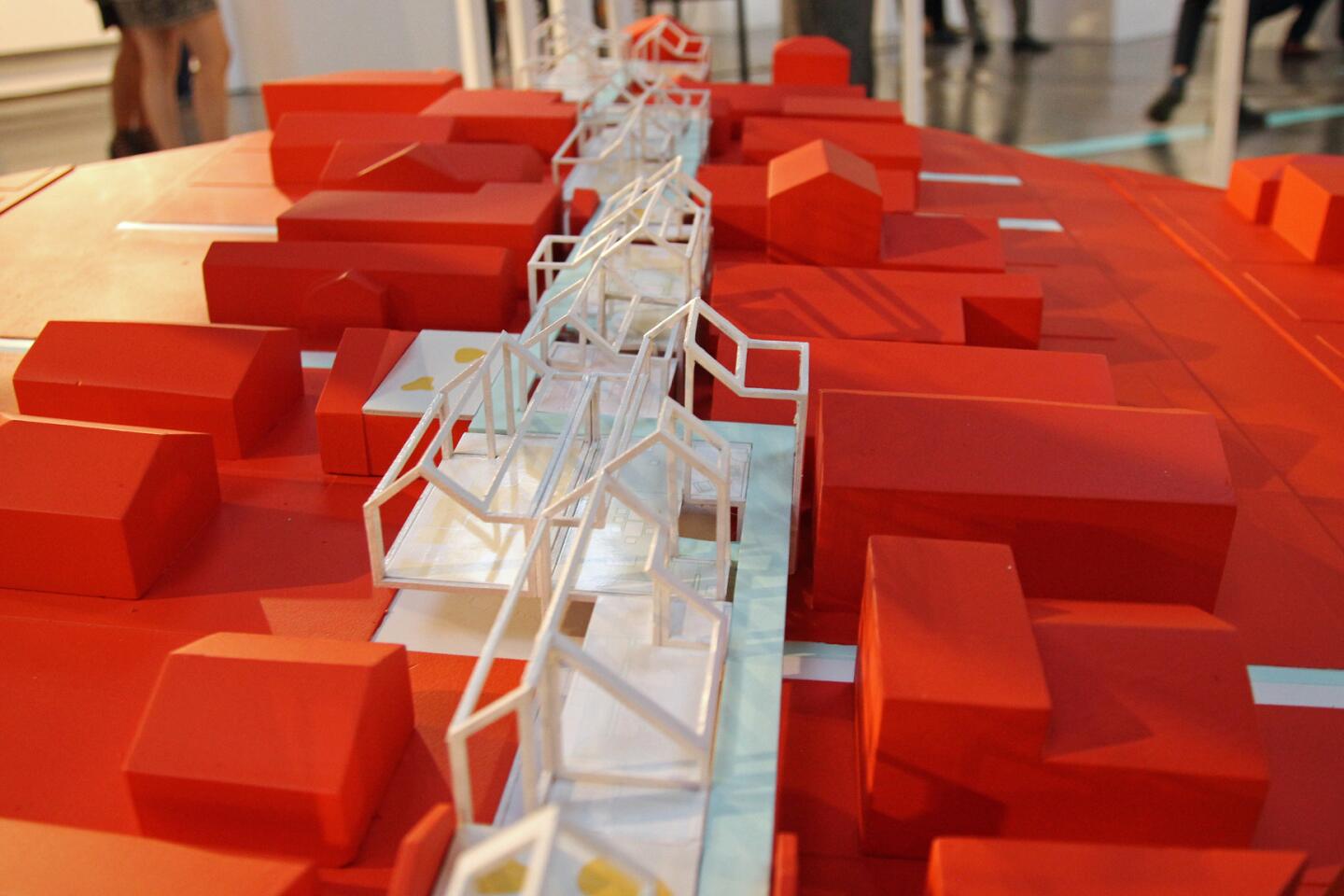

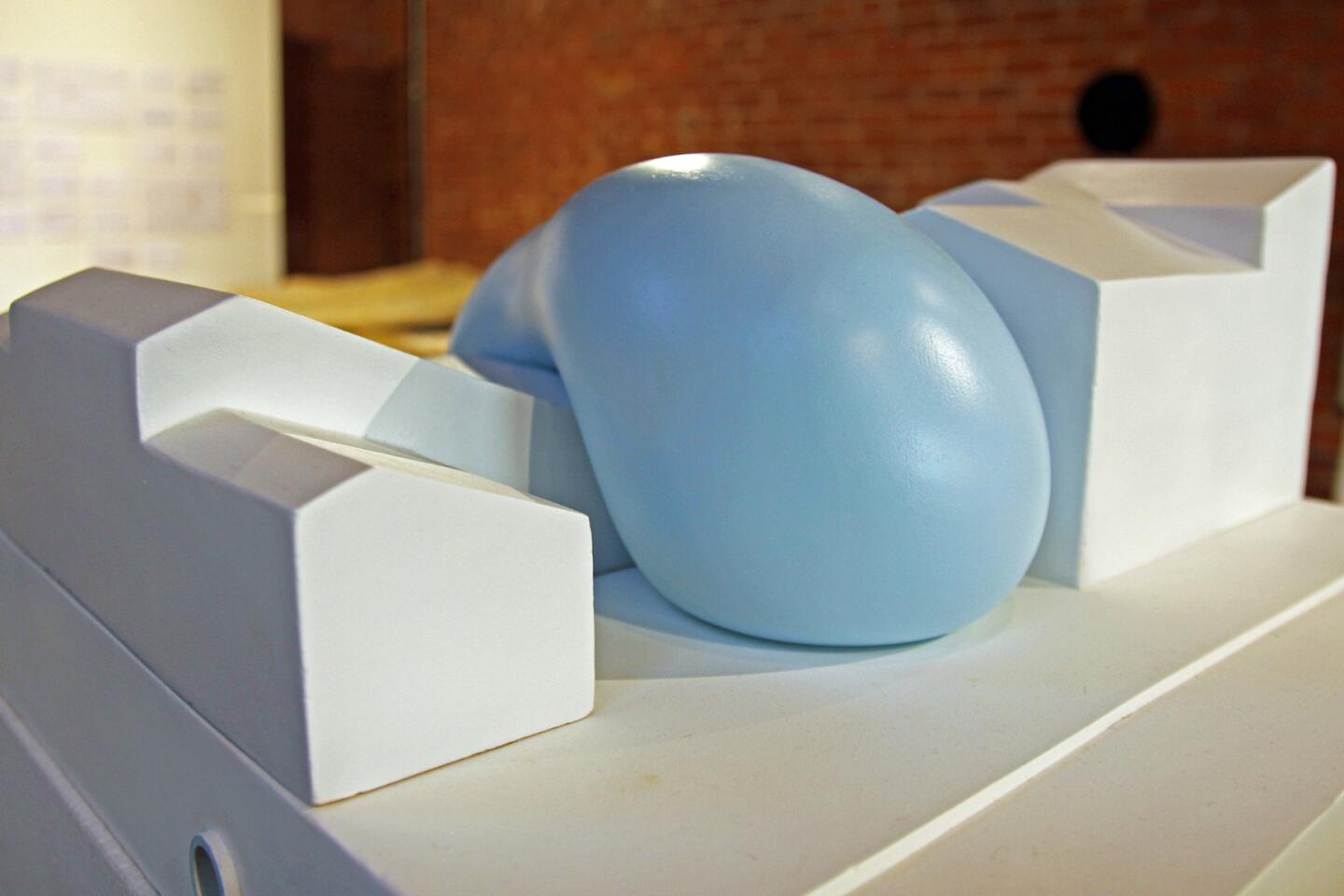

A concept design by wHY Architecture proposes a pair of slim, sci-fi structures that would occupy two lanes of Wilshire, complete with elevated parks and swimming pools. Across the room, a cluster of powder-blue models by Lorcan OâHerlihy Architects imagines homes that can capture and purify rainwater â one with a giant sponge, another with a bulbous architectural bladder. There are futuristic towers, Queen Anne houses that have had their guts rearranged and a blockâs worth of granny flats reconfigured into a single, efficient belt.

âShelter: Rethinking How We Live in Los Angelesâ looks at the future of housing in L.A. And it does so with some purposely radical designs. (One can only imagine the pandemonium that would erupt among the membership of the Miracle Mile Residential Association if they got a gander at the hyper-contemporary concrete ribbon proposed by Kulapat Yantrasast and the team at wHY for Wilshire.)

But the out-there ideas are for a reason: to get designers, city planners, developers and design-interested citizens thinking about what the L.A. of the not-so-distant future will look like â one in which the single-family home is not the model.

âLos Angeles is facing greater density,â says Sam Lubell, who co-curated the exhibition with Danielle Rago. âItâs facing affordability issues, environmental issues. So the goal is to rethink models of housing in L.A. with some of those questions in mind.â

The bulk of the show is focused on the forward-looking designs of six architectural teams from Los Angeles: wHY, Lorcan OâHerlihy, Bureau Spectacular, Par, MAD and LA-MĂĄs.

Barbara Bestorâs Blackbirds development is centered around a private lane that could be used for block parties or as a place for kids to play. The project adds density but preserves access to outdoor space.

But one wall is devoted to more than a dozen L.A. designs that have actually been built, projects that employ innovative methods of construction, have higher levels of density, dialog well with the outdoors and achieve all of that with an interesting nod to design. In other words, they show that high density doesnât have to mean a big, impersonal box.

Over the past couple of weeks, I toured four of these completed projects and spoke with their architects (all of whom are Los Angeles-based). And I hit points east and west: Michael Maltzanâs Star Apartments on Skid Row, Barbara Bestorâs Blackbirds residential development in Echo Park, Lorcan OâHerlihyâs student and faculty apartment complex in Westwood and Kevin Daly Architectsâ Broadway Housing in Santa Monica.

The goal was to get a sense of what has already been accomplished architecturally in Los Angeles and what we could learn from these projects moving forward â from how to share space to what aspects of the L.A. building code need reconsidering if weâre going to design smartly in the future.

Here are five lessons learned:

1. The homes of the future will have greater density and smaller footprints

âLos Angeles has sprawled for almost all of its history,â Maltzan says. âEvery time it was given an opportunity, it pushed the perimeter further and further out. And I think that thereâs an argument to be made that the limits of that perimeter have finally be hit â whether for geographic or psychological reasons.â

The projects I visited all treated space with great care. OâHerlihyâs 31-unit Westwood apartment building features two- and three-bedroom apartments that are 800 and 1,000 square feet, respectively.

At Bestorâs Echo Park project, which is comprised of 18 houses in a medium-density development on a hillside, the largest of the bunch is 1,900 square feet â and it harbors a three-bedroom, two-and-a-half bath house. These are a far cry from 10,000-square foot McMansions.

Certainly, the move is about using space more efficiently â fitting more people into the same acreage. But itâs about something else, too.

âWeâre used to L.A. as a single-family home with a garden and the garage and the driveway,â says Bestor â but that lifestyle is changing. âPlaces like Venice have set an excellent precedent. The lots are tiny, but they command as much as a mansion in Bel-Air. Why? Youâre buying into lifestyle. You can walk around. You can pop over to the corner store.â

In other words, a comfortable living experience is not always about having the biggest place.

2. Outdoor space will be communal

âItâs all about shared space,â Lubell says of the future L.A. âYou donât get your own outdoor space anymore.â

Every project I visited was centered on or contained a shared outdoor space. Dalyâs Santa Monica project â a development of 33 affordable-housing units â is built around a courtyard that is shaded by a decades-old quinine tree. Bestorâs homes are set around a narrow lane that also serves as a gathering space or childrenâs play area, one that is protected from the street traffic on Vestal Avenue.

At Maltzanâs Star Apartments in downtown Los Angeles, the second story is largely open to the elements and features a vegetable garden, a pickleball court and a rubberized running track.

At OâHerlihyâs Westwood housing â which happens to face the historic Strathmore Apartments, designed by modernist Richard Neutra in the 1930s â various terraces have been cut out of the building to provide an intimate space in which to gather, chill out or study.

Despite the stereotype of the single-family home, this type of shared public space is in Southern Californiaâs architectural veins. Says Bestor: âWe canât ignore the history of the courtyard apartment in Los Angeles.â

3. Thoughtful outdoor space is what sets L.A. architecture apart

In recent years, L.A. has seen a significant amount of high-density building: apartment buildings clustered along La Brea and Wilshire, multifamily developments around downtown, blocky condo developments in Alhambra. The attention to any kind of outdoor space in many of these projects often looks like an afterthought â consisting of a balcony wide enough to accommodate a bicycle or, in some cases, nothing more than a driveway.

In a place like Los Angeles, where good weather is part of the charm, it should not be like this. And the projects on view at A+D remind us that medium- and high-density projects can provide access to interesting and comfortable outdoor areas.

OâHerlihyâs Westwood apartment building â which occupies a sliver of steeply graded land at Strathmore Drive and Levering Avenue â has various terraces cut into the building, thereby providing pleasant open-air gathering areas. (These also have the effect of reducing some of the buildingâs mass so as not to block Neutraâs historic apartments across the way.)

âI always try to persuade clients that projects will be stronger by integrating outdoor space in a thoughtful way,â OâHerlihy explained as we toured the perimeter of his project. âIt can change the dynamics of a building.â

On my visit to Dalyâs Broadway Housing in Santa Monica, kids were playing around the grown trees that served as the centerpiece of the design. Some of Bestorâs units had private patios, but the communal lane assures that everyone had access to the outdoors. The roomy second story terrace of Maltzanâs Star Apartments, in the meantime, offers charm and good views amid the grit of downtown.

âAs opposed to importing models from more traditional cities, itâs incumbent on us to deal with density on our own terms,â Maltzan says. âAnd it needs to come from the undercurrent of life and lifestyle here. ... So, finding a way to more inventively create a better balance between high levels of density and generous open space is not just a nice marketing thing. It gets at the very core of how you begin to transform one way of living into another way of living.â

âLos Angeles,â Lubell adds, âdoesnât want to do density the way New York does density.â

4. The city needs to make way for innovative building and design

Any builder who has worked on a project in Los Angeles knows that this is a space that is highly regulated â which means that trying anything new oftenis impossible. This was a problem that Maltzan faced during the design and construction of the Star Apartments.

The buildingâs stacked and staggered apartment units â which give it a kind of Tetris feel â are prefabricated. And these were all laid into place using a crane. There are a lot of reasons to want to build with prefabricated units in Los Angeles: The build time is shorter, and the construction doesnât require acres of staging areas. Plus, the prefab units often make a much more efficient use of materials than construction done on-site.

âAs you work with a manufacturer, you can keep refining the design until they use every single piece of material that comes in,â Maltzan says. âFrom a sustainability point of view, the prefabrication process is about minimizing construction waste.â

But Los Angeles has no real way for contending with this type of construction. In fact, prefabricated units are considered âproductsâ by the city and therefore require all kinds of onerous and expensive labeling. Maltzan had to work with the regulators to find a way around that.

âMuch of the Star Apartments in the beginning,â says the architect, was not about design. â[It] was working with the city of Los Angeles to develop a pathway by which you could more easily build and develop a multifamily construction employing prefabrication.â

In other words, there was a whole lot of negotiation and a whole lot of paperwork.

Los Angeles doesnât want to do density the way New York does density.

— Sam Lubell, co curator of âShelterâ at the A+D Museum

5. Parking requirements are in desperate need of an update

Of all the regulations that guide design and construction, parking is one of the issues that needs to be dealt with most urgently.

Los Angeles has onerous rules about parking. A single-family house has to have two covered parking spaces. A two-family residence requires one-and-a-half covered spaces and half an uncovered space. (You read that right.) Apartment houses need a jigsaw puzzleâs worth of covered and uncovered spaces in wholes and halves. The code is mind-boggling.

âItâs such an anachronism â and so out of date,â Daly says. âAre we really building 400-square-foot structures for cars? That should go to the home or the garden.â

At a time when increasing numbers of young people are using public transit, when the city is in the midst of reconfiguring its street grid to cut car lanes in favor of bus- and bike-ways, the parking requirements are going to have to give.

The team at wHY points this out in a text that is part of its A+D Museum installation: âWith most housing development projects, a parking study is the first test of viability,â it reads, âbut will we need so much space in the future?â

Perhaps we should look to the affordable-housing model, which doesnât require as much parking as part of its zoning.

âThe modest break on parking makes such a difference from a design perspective,â Daly says. In the case of his Santa Monica project, âit allowed us to add another floor.â It also allowed Broadway Housing to hold onto its fully grown trees, which grow directly into the earth and not some artificial concrete planter. For the residents of the apartments, itâs like having a built-in park.

Bestor says the small-lot ordinance that governed her Echo Park project also offered a break. (Some of the Blackbirds units come with uncovered parking only.) âI didnât have to be as concerned with the parking, and that allows for more density,â she says.

âBesides,â she adds, âsometimes uncovered parking can be a better use of space since people have to park their cars there. In L.A., most people use their garages as everything except a garage.â

âShelter: Rethinking How We Live in Los Angeles,â is on view at the Architecture + Design Museum through Nov. 6. 900 E. 4th St., downtown Los Angeles, aplusd.org.

I discuss the show with Frances Anderton of KCRWâs Design and Architecture program. You can listen here.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.