Commentary: Thomas Mann house by midcentury great J.R. Davidson: L.A.âs next big teardown?

From the street, David Gebhard and Robert Winter noted in the second edition of their still-indispensable guide to Los Angeles architecture, âIt is almost impossible to see the International Style house of the great novelist Thomas Mann. It is a pity since the Manns were so deeply involved with the planning. We list it because of the thrill of knowing it is there.â

How much longer it is liable to be there â there being a large corner lot on San Remo Drive in Pacific Palisades, just north of the Riviera Country Club and about three miles from the Pacific â is now a pressing question.

The house, which Mann and his wife, Katia, commissioned from architect J.R. Davidson and built in 1941, after moving to Southern California from Princeton, N.J., by way of Switzerland and Germany, is on the market with an asking price of $14,995,000. It sits on nearly an acre of land.

It is being marketed as a tear-down. There is no mention in the listing of its connection to Mann, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1929, or Davidson, a fellow German ĂŠmigrĂŠ best remembered for designing three houses as part of the postwar Case Study program sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine.

Although the language in the listing â âCreate your dream estate or remodel and expand the existing home in the ultra-exclusive upper Riviera neighborhoodâ â hedges its bets a bit, Joyce Rey, the agent representing the seller, was more direct in a phone interview, saying she had a hard time imagining that any potential buyers would be interested in its history.

âThe value is in the land,â she said. âThe value is not really in the architecture, I would say.â

The uncertainty surrounding the house is a reminder of how unusually fragile the cultural patrimony of Los Angeles remains, since so much of it is contained not in public spaces or buildings but in the private realm. To a degree rare among major world cities, L.A.âs civic heritage is a scattered collection of (official and unofficial) house museums often vulnerable to the whims of their owners.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter Âť

Like news of the cholera epidemic spreading through Italy in âDeath in Venice,â Mannâs 1912 novella, reports that the house was on the market were spotted first in the German press.

They arrive less than two years after Los Angeles architect Thom Mayne demolished a modest yellow house in the Cheviot Hills neighborhood owned for five decades by Ray Bradbury. Mayne is building a house for himself and his family in its place. As a token remembrance of the writer, Mayne has said, it will include an outer wall etched with the titles of Bradburyâs books.

The Mann house would be a bigger loss. Unlike Bradburyâs residence, it is a work of real architectural significance on whose design the novelist and his wife collaborated closely with Davidson.

It is not just the house, in other words, where Mann wrote âDoctor Faustusâ and âThe Holy Sinnerâ; it is also a portrait of his artistic temperament and a measure of his relationship with Southern California â and with architectureâs modern movement.

The house is not one of L.A.âs official historic-cultural monuments, though it is listed as a âhistoric resourceâ in a larger inventory called SurveyLA. A new citywide ordinance requires that owners seeking to demolish houses older than 45 years provide notice to neighbors and the local city council office at least 30 days in advance. But in general there are limited protections for most residential buildings in Los Angeles, even those with notable architectural pedigrees.

Rey said the seller, whom she declined at least for the time being to identify, was not interested in opening the house to preservationists or journalists. That will it make it tough to determine precisely what kind of shape it is in.

L.A.’s civic heritage is a scattered collection of (official and unofficial) house museums often vulnerable to the whims of their owners.

Seeing it from the base of its long driveway at the corner of San Remo and Monaco Drive has, if anything, grown more difficult since Gebhard and Winter first wrote about the house in 1977. A row of eucalyptus trees is filled in at street level by a collection of hedges.

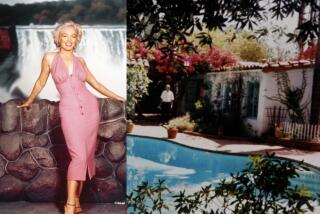

Photographs published online when the house was put up for rent in 2012 (at a cool $15,500 per month) suggest that while some less-than-authentic updates and what appear to be modest additions have been made, its architectural integrity remains at least somewhat intact.

Before picking Davidson, Mann made a careful study of L.A.âs leading architects. According to Ehrhard Bahrâs âWeimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism,â he arranged a tour in 1938 with the Austrian-born architect Richard Neutra of important new houses here.

Many local architects assumed the commission was Neutraâs to lose. But Mann had reservations both about the clinical quality of much orthodox Modern architecture â he wrote in his diary in 1938 about how much he disliked the âcubist glass-box styleâ â and about Neutra himself, who according to architectural historian Thomas S. Hines offended Mann by making an aggressive pitch for the job at a party thrown by writer Vicki Baum.

In the end, Mann and his wife found a far better match with Davidson, who had left Berlin for California in 1923 and whose style was more moderate than Neutraâs as well as a touch more romantic. As one report from Germany put it this week, the house Davidson designed for them is a gemĂźtlich, or comfortably agreeable, spin on the modern.

In that sense, it is not quite right to label the house, as Gebhard and Winter do in the 1977 second edition of their guide, an example of the International Style. Davidson called it ânostalgic German,â though it is nostalgic only compared to the work of unrelentingly forward-looking architects like Neutra or Walter Gropius. (Or perhaps nostalgic for the earliest buildings of those architects.) Photographs of the house when it was new show the unadorned surfaces and bands of plain windows common in Bauhaus architecture but also bedrooms set back to make room for terraces topped by a continuous built-in pergola.

The effect is a piece of architecture entirely comfortable in and even ceding some glory to the surrounding landscape, not unlike the house and studio Charles and Ray Eames would build for themselves nearby at the end of the 1940s.

(In later editions, Gebhard and Winter changed the wording a bit and described it as âa stucco-and-glass two-story Modern image house,â meaning it aims for the general impression, rather than following every rule, of modernism.)

Mann left Los Angeles and returned to Europe in 1952, alarmed by the rise of McCarthyism and red-baiting. According to writer Jeffrey Meyers, he âwas deeply disillusioned by the toxic political atmosphere that reminded him of the Hitler years.â He died in Switzerland in 1955.

Though the asking price of the Mann house will be daunting for any preservation-minded buyer, there is at least one precedent when it comes to protecting the legacy of the accomplished German ĂŠmigrĂŠs who settled in Los Angeles.

The Villa Aurora, also in Pacific Palisades, is the former home of writer Lion Feuchtwanger and his wife, Marta. A nonprofit group based in Berlin bought and restored the house with financial help from the German government; since 1995 it has operated as a cultural center with a residency program for visiting artists, its rooms lined with more than 20,000 books from Feuchtwangerâs own collection.

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

ALSO

Brazilâs modern look: Why Olympic viewers should know the name Roberto Burle Marx

Check out the latest details on Peter Zumthorâs new LACMA building

How to remake the L.A. freeway for a new era? A daring proposal from architect Michael Maltzan

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.