Why âThree Billboardsâ and âCall Me by Your Nameâ leave this theater critic cold

Like many Americans, I find it increasingly easy to talk myself out of going to the movies. Thereâs plenty to watch at home and so little to lure me back onto the roads and into those unfathomable parking structures from which no car is guaranteed of returning.

But awards season has a way of concentrating the middle-aged mind. As a drama critic who would rather read, whittle down the DVR listings or dart mindlessly down internet holes on his night off, I still consider it an obligation to support the handful of movies not targeted to the reptilian brain of tweens. But more to the point, I long to see my life reflected on the screen, and last I checked there was no flying saucer or caped muscleman flying outside my window.

2017 has departed without much regret, yet the year in movies wasnât nearly as depressing as the year in politics. If there wasnât a film that separated itself from the pack, an instant classic to gather up all the golden bric-a-brac and convince Americans that we really are a united people, there was enough evidence that we are living in fertile moviemaking times.

Any year that can make room for the biting originality of Jordan Peeleâs âGet Out,â the bespoke detailing of Paul Thomas Andersonâs âPhantom Thread,â the invigorating feistiness of Greta Gerwigâs âLady Bird,â the controlled sensory overload of Christopher Nolanâs âDunkirkâ and the timely conscience of Steven Spielbergâs âThe Postâ canât be all bad. These films may have divided audiences, but what beyond basic arithmetic can any of us agree on today? I donât wish to make inflated claims, but I donât regret leaving the house for them. They did what I expect movies to do: allow me to lose myself in the dark for a couple hours, entranced by the power of big-screen storytelling.

That was not my experience with two awards contenders I felt sure would satisfy my seasonal yearning for intelligent filmmaking. I rushed to see Luca Guadagninoâs âCall Me by Your Nameâ (based on the novel by AndrĂŠ Aciman) and Martin McDonaghâs âThree Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouriâ (the latest film from the comically ruthless Irish-English playwright), but neither created a convincing enough reality to seize hold of my imagination and unsnag me from my qualms.

In both cases, I found myself quarreling with the writing, much as I had earlier in the year when I saw âA Quiet Passion,â the overtouted Terence Davies film about Emily Dickinson. I couldnât understand how friends and fellow critics could overlook the implausibilities of language, character, culture and plot that repeatedly wrenched me out of the fictional moment. I envied them, but wondered if McDonaghâs overblown reputation as a theatrical insurgent and the combination of Guadagninoâs insistent artiness and Acimanâs self-conscious literariness may have hoodwinked them.

âThree Billboardsâ strikes me as a screenplay in search of a stage. McDonagh began as an enfant terrible of the English-speaking theater, an iconoclast who, in plays such as âThe Beauty Queen of Leenaneâ and âThe Pillowman,â wreaked bloody havoc on theatrical stereotypes and comforting middle-class clichĂŠs.

A master technician with more defiant verve than depth of vision, McDonagh successfully deployed his patented gift for making laughter scald like battery acid in his film âIn Bruges,â a black comedy about hired assassins holed up in the medieval Belgian city. Treated as a tourist pop-up book, Bruges serves as a humorous backdrop for this fish-out-of-water tale about two Irish killers laying low in a ludicrously quaint town with nothing to do but bicker, sightsee and brood over their fates. âThree Billboards,â by contrast, wants to enjoy its stagy revenge drama while rolling through the American landscape.

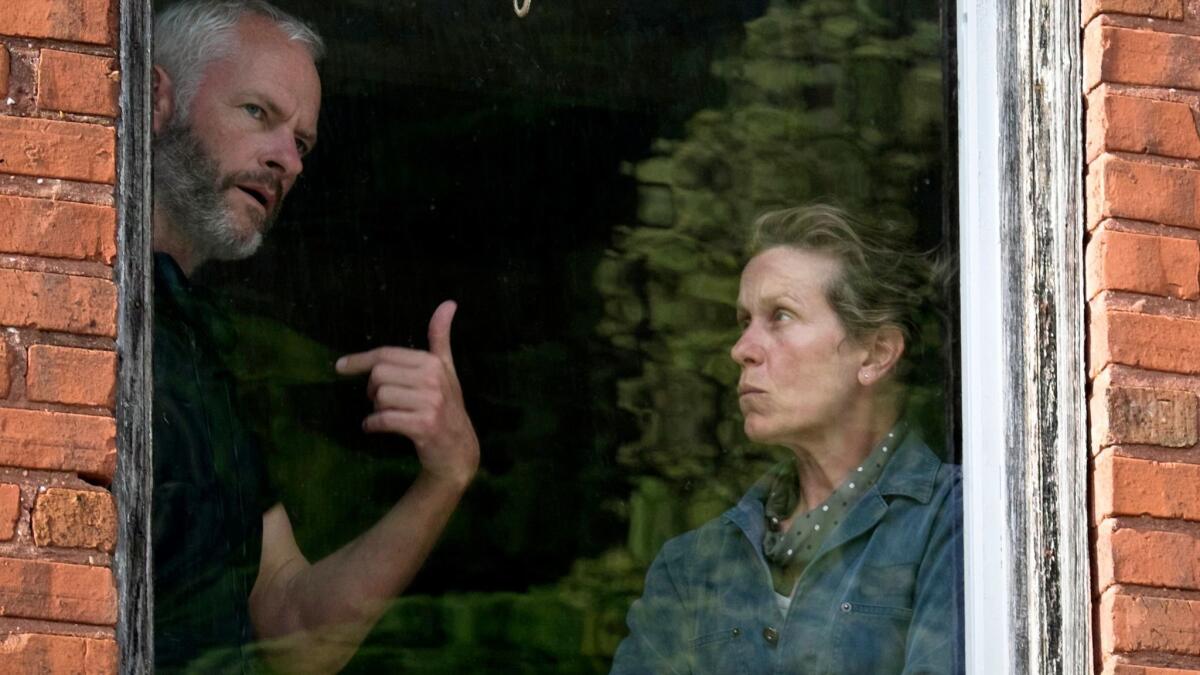

Frances McDormand will likely win an Oscar for her no-holds-barred performance as Mildred, a wrathful mother frustrated by the failure of the local police to find the maniac who raped and killed her daughter. McDormandâs avenging, crotch-kicking boldness provides a cinematic capper to a long overdue cultural moment of female empowerment.

As a McDormand vehicle, the film has a satiric western swagger, updated by the casting of a woman of a certain age in the vigilante role. McDonagh complicates Mildredâs story by showing how the lust for justice can grow depraved the longer it is denied â a favorite subject of dramatists going back to Aeschylus.

But the filmâs comic contrivances and extravagant banter can seem incongruous in a dramatic context that flips between grotesque parody and gritty realism. The twee artificiality of the town suits the chiseled dialogue better than the long shots of natural scenery, which recur whenever we return to the trio of billboards Mildred has rented out to vent her spleen at the police chief, whoâs frustrated by his own inability to solve the case.

I couldnât understand how friends and fellow critics could overlook the implausibilities of language, character, culture and plot.

The film was shot in North Carolina, but the only map Ebbing can be found on is the one in McDonaghâs imagination. If the example of Quentin Tarantino is unmistakable, so too are the influences of Oscar Wilde and Harold Pinter in a movie that grows intoxicated with its own caustic repartee. McDonaghâs verbal swashbuckling, an imported sport, might as well be flying a Union Jack.

Tonally, âThree Billboardsâ is as antic as its soundtrack, which darts from folk to opera to blues to patches of melancholy strings. Irony and sarcasm dominate, yet more vulnerable sentiments are permitted to crop up between punchlines. Such variety can be a sign of artistic complexity, a postmodern refusal to hew to predictable patterns of genre. But awkwardly calibrated, the film seems at loggerheads with itself.

The scene in which Mildred firebombs the police station has all the campy mischief of the old âBatmanâ TV series with Adam West, but then Dixon, the racist cop memorably played by Sam Rockwell, is gruesomely burned. The violence, which includes Woody Harrelsonâs terminally ill police chief blowing his brains out, stops the laughter. But I found myself flinching more in annoyance at the way the film rubs our noses in the gore. The brutality is neither credible enough for serious drama nor cartoonish enough to laughingly dismiss.

Warped by fury, Mildred acts callously not only to those who deserve it but also to the little person (played by Peter Dinklage) who provides her with an alibi for the firebombing. (McDonagh clearly has a weakness for âmidgetâ jokes.) As she proved in the HBO miniseries âOlive Kitteridge,â McDormand can keep us on her side even when her character is at her unsentimental worst. But I experienced a growing impatience as the camera, taking a breather from the corrosive comedy, closes in on Mildred peering somberly into the middle distance. McDonagh doesnât usually sugar his strychnine.

The actors are impressively agile, but the film confounds with mixed signals. McDonagh is clearly trying to move beyond the straitjacket of violent comedy. But in blurring the difference between the world he contrives and our own, he exposes his limited understanding of American culture and undermines his unique strengths as a fiendish comic fabulist.

Set in Northern Italy in 1983, âCall Me by Your Nameâ offers the surface pleasures associated with Merchant-Ivory films â lush estate grounds, tony interiors, vivid period clothes and sumptuous nakedness. James Ivory wrote the screenplay based on Acimanâs novel about a romantic encounter between a professorâs precocious teenage son and the gifted graduate student who spends part of the summer at the professorâs country villa.

The book is elliptical in a manner that is seductive, open-minded and ultimately unsatisfying. Aciman leaves out too much of the story, investigating only those parts of the charactersâ lives that suit his airily philosophical, overly romanticized purposes.

Ivory doesnât have much success in filling in the elisions, but Guadagninoâs direction compounds the superficiality with camerawork that canât resist fondling every surface it encounters. The film is as sleek as an orgy co-sponsored by Travel + Leisure and GQ.

TimothĂŠe Chalametâs performance as Elio, the professorâs multilingual son, is a marvel. The camera loves him â maybe a little too much. Thereâs only so much meaning that Guadagnino can derive from a slim, hairless torso.

Itâs a fantasy for those afraid of their fantasies.

But the love story between Elio and Oliver, the visiting student, is hampered by the casting of Armie Hammer, who resembles not so much a budding archaeologist with a deep knowledge of philology but a junior associate at Goldman Sachs with a wad of travelerâs checks in his preppy shorts. Hammerâs Oliver seems too old, too confident and too blunt for the delicate affair whipped up for him.

The erotic adventure of the young men is art-directed to be poetic (secret foot massages!) rather than convincingly candid. âCall Me by Your Nameâ wants to depict sexuality given a furlough from societal prohibitions, but the film would rather not delve into the psychology of the closet. Identity politics neednât be rigidly brought into the story, but sexuality and selfhood seem to have only a passing acquaintance here. Itâs a fantasy for those afraid of their fantasies.

Thereâs nothing in the movie as gripping as that moment in the 1987 film âMaurice,â which Ivory directed and co-adapted from E.M. Forsterâs novel, when James Wilbyâs Maurice and Hugh Grantâs Clive finally succumb to tenderness as students at Cambridge University. Mauriceâs unstoppable caress of Clive, whoâs seated beneath his chair, is reciprocated with an upstretched hand that promises more than upper-class English society in the early part of the 20th century can accommodate. Their silent interaction is more eloquent than all the academic smart talk in Ivoryâs screenplay.

âCall Me by Your Nameâ has only marginal interest in its female characters, who are seen chiefly in relationship to the needs of the men around them. More problematic is the handling of Elioâs father (played by Michael Stuhlbarg with his dependable dexterity), who lives vicariously through his sonâs sexual awakening. He has been supervising Elioâs sentimental education like a paternal, voyeuristic Flaubert.

Near the end of the film after Oliver has returned home, Professor Perlman passes along some sage words to his son about treasuring the quickly fading springtime of passion. âCall Me by Your Nameâ would rather generalize this romantic wisdom than explore its neurotic origins in the professorâs walled off homoerotic desire. Perlman lives in a morgue of good living that the movie confuses with timeless philosophy.

All the sexy cinematography is ultimately a subterfuge, a mythological screen to divert attention from a more shadowy story of cowardice and compromise. The endless scrutiny of Chalametâs face as it shades from innocence to experience through the pain of loss makes for a striking finale. But the profundity of âCall Me by Your Nameâ is shallow. The house is full of books and literary references are strewn about like confetti, but the overriding sensibility is more decorative than dramatic â Merchant-Ivory for the age of Instagram.

Perhaps my expectations for âThree Billboardsâ and âCall Me by Your Nameâ were unduly raised by all the awards buzz, but I was unable to stay immersed in their fictional worlds. (âThe Shape of Water,â Guillermo del Toroâs romantic fable about a sea creature and a mute custodial worker, did a better job of keeping me submerged.) As this yearâs Oscar hopefuls attest, filmmakers can conjure any reality, as long as they donât wake you from the spell theyâre casting.

Follow me @charlesmcnulty

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.