Review: Bellini masterpieces at the Getty make for one of the year’s best museum shows

In his depiction of Jesus newly risen from the tomb and lifting his right hand in gentle blessing, painted around 1500, Giovanni Bellini represents Christianity’s savior as the morning dawn. At the far right, the bell tower of a distant town pierces the incandescent horizon, poised to toll and announce the arrival of a new day.

In this extraordinary masterpiece ‚ÄĒ one of 12 pictures in ‚ÄúGiovanni Bellini: Landscapes of Faith in Renaissance Venice,‚ÄĚ newly opened at the J. Paul Getty Museum ‚ÄĒ sunrise is breaking, its cloud-streaked sky washed in diaphanous smudges of orange, yellow, pink and blue. Yet the sun cannot be the source of the body‚Äôs illumination, which comes in from the opposite direction at the left front.

Shading tells the story ‚ÄĒ not least in the raised arm‚Äôs exquisite shadow falling across the figure‚Äôs classically defined chest. The pictorial illumination is impossible but thoroughly believable, miraculous but convincing. Soft, translucent glazes of oil paint make the painting shine with an inner light.

In the middle ground, barren branches of a dead tree rise next to Christ’s blessing hand, juxtaposing a symbol of death and the cross with a gesture of salvation. Through art, the radiant figure and the luminous landscape unite as one.

Bellini‚Äôs brilliant use of landscape is the subject of the Getty‚Äôs exhibition, which is among the most exciting museum shows in the United States this year. Bellini launched the so-called Golden Age of Venetian painting, characterized by the sensuous, luminous color and acute conceptual refinement on breathtaking display in ‚ÄúChrist Blessing.‚ÄĚ

The last time I recall seeing a considerable number of his paintings in an American museum show was 11 years ago, when ‚ÄúBellini, Giorgione, Titian, and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting‚ÄĚ was at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Much of Bellini‚Äôs work is painted on wooden panels, and loans are difficult to negotiate. That path-breaking exhibition had six marvelous paintings by the artist.

The Getty’s 12 have been assembled from public and private collections in Venice, Florence, Paris, London, the United States and elsewhere.

Remarkably, Getty senior curator Davide Gasparotto has organized what appears to be the first monographic exhibition on the artist ever in an American museum. It‚Äôs modest in size (there‚Äôs also one drawing, a ‚ÄúNativity‚ÄĚ from around 1470) and fits in a single gallery; but it‚Äôs a room of exceptional artistic grace and power.

The show is tightly focused on devotional paintings rather than the altarpieces and larger works at which Bellini also excelled. Devotional paintings are meant for contemplation, up-close and personal, one on one. Four crucifixions side by side on one wall offer a stunning array of varied takes on a single theme central to the faith.

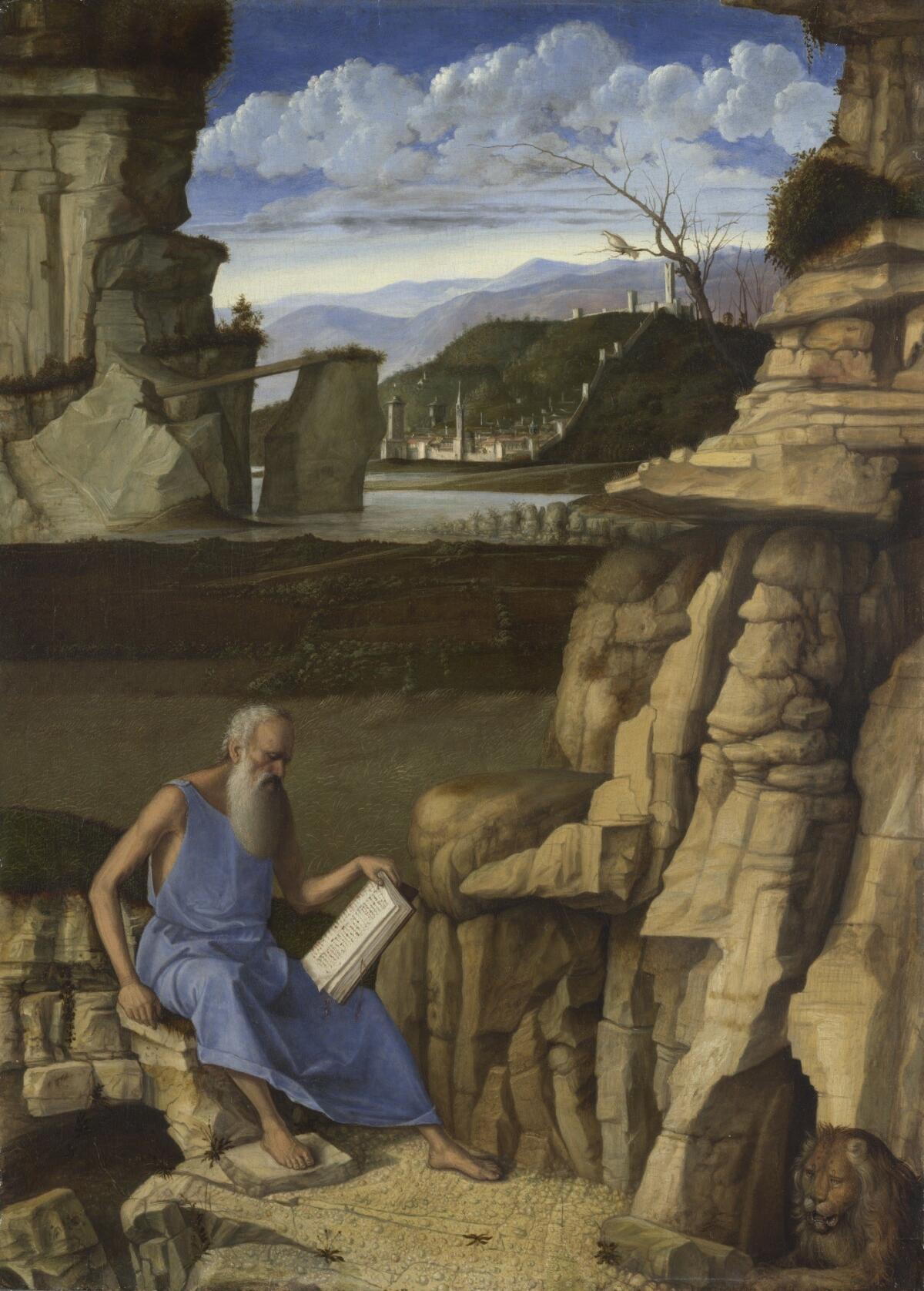

So does a second wall with three versions of St. Jerome, the late-4th century hermit-scholar, who withdrew from society for lengthy periods of solitude in the Syrian desert. One is from around 1455, when Bellini was just starting out; the shape and burnt sienna color of the fierce but suffering lion with a sharp thorn stuck in his outstretched paw, which the compassionate saint would remove, is strangely echoed in the rock formation of the cave in which the wizened Jerome sits.

The next is from 30 years later, and the third is from 20 years after that, a decade before the end of Bellini’s life (he died in 1516). By then, the Venetian Renaissance was in full swing. The full arc of Bellini’s career unfolds.

For the wealthy patrons who could commission a devotional painting ‚ÄĒ and for lucky us in the museum today ‚ÄĒ the sight of St. Jerome deep in thoughtful study pictures the same contemplative analysis in which a viewer is engaged. Bellini‚Äôs artistic mirror creates a powerful bond.

But the artist‚Äôs particular reflection also exploits a profound difference. St. Jerome is always shown poring over a written manuscript. (He was the first to translate the Bible‚Äôs Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek into Latin, a more universal and thus more influential language.) Rather than words, a painting is a physical, concrete object. Bellini painted ‚Äúthe Word‚ÄĚ into artistic flesh.

The three St. Jerome panels encompass the painting materials Bellini employed. The first is in tempera, a hard, durable, ancient medium that allows a crisp line and satiny sheen; the third is in oil paint, with a soft, transparent, luminous effect; and in between them, the second is in a mixture of the two, both tempera and oils.

It is a myth that Bellini introduced oil painting, perfected in Northern Europe, to Italy, and that he abandoned tempera when he realized oil paint’s seductive power. Instead, he used both throughout his life. But it is certainly true that the arrival of oils, followed by the use of canvas rather than wooden panels as a support, sent the Venetian Renaissance into orbit at the hands of Titian, Giorgione, Veronese and the rest.

Speaking of materials, one of the crucifixion panels is a puzzlement. The surface is scattered with tiny sparkles, almost as if glistening bits of glitter are embedded in the paint. Gasparotto, the curator, told me the effect might be produced by tiny worm holes, not uncommon in 500-year-old wooden panels.

If so, I wonder whether the sparkle might come from tiny bits of pulverized glass in the paint. (Apparently the pigments haven’t been scientifically tested.) One marvelous revelation of the great National Gallery survey in 2006 was that many artists mixed finely ground and brightly colored glass, plentiful in Venice’s celebrated Murano workshops, into their paint. Glass juiced the picture’s colorful luminosity through reflected light.

Both the St. Jerome paintings and the crucifixions, like the ‚ÄúChrist Blessing‚ÄĚ and other panels, demonstrate the Getty show‚Äôs main point: They highlight Bellini‚Äôs transformation of passive natural landscapes into active protagonists.

A Bellini landscape is a full-fledged character. Often it is as complex and meaningful as the people portrayed, from whom it is inseparable.

One of the clearest demonstrations is a crucifixion from the Corsini Collection in Florence. Although a bad cleaning job undertaken more than a century ago harmed the color, the composition is clear. Christ’s body hangs heavily on the cross, his broadly outstretched arms forming a graceful upward curve. Behind and below him in the middle ground, the contour of a pair of rocky mesas repeats the arc in a parallel curve.

More than merely a formal or stylistic echo for simple pictorial harmony, the emphatic repetition visually unites figure and landscape, cupping the distant land, sea and sky between them. This radiantly enclosed universe performs a stark contrast with the barren earth of Golgotha into which the cross is planted.

There the skull and bones of Adam are strewn across the dusty foreground. The crucifixion stands as the path between the earthly and the heavenly, shifting from the Old Testament to the New. Christ is the New Adam, and the landscape is our guide.

A second, very different emotional layer also reverberates against this anguished scene of suffering and death. The two rising, upturned arcs are as if Jesus and the world have united in a triumphant gesture of exultation, like a hero before a throng.

If Bellini’s painted landscape looks nothing like the hard and arid natural one outside the actual walls of Jerusalem, where the biblical event took place, that’s because his version echoes the soft, green, seaside expanses of the Veneto. When Bellini was born, around 1435, Venice was the most powerful city in Italy. But its fortunes began to change after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire, when Bellini was still a teenager.

The maritime city of lagoons, still splendid and rich, slowly turned away from prosperous sea-faring trade in luxury goods from the East, source of its historic wealth, and toward its future to the West. There lay the verdant landscape of Italy, which Bellini began to absorb into the subjects of his art.

The city‚Äôs thousand-year history with Byzantium lingered. The frontal, half-length format of the intensely focused ‚ÄúChrist Blessing‚ÄĚ is virtually a Byzantine icon ‚ÄĒ albeit now relaxed by softened forms and tempered with the closely observed, Italianate landscape that unfolds behind the figure.

Such landscapes surely meant something powerful to the patrons who bought Bellini’s art. They were, after all, city dwellers. The pastoral landscape was a natural retreat from the urban toil and intrigues of a place constructed from scratch on pilings erected atop watery marshes. Nature and society were different realms.

Like St. Jerome leaving Rome for the solitude of the desert, a Venetian doge or merchant could conceptually retreat by silent study of the landscape in an exquisite devotional painting. Bellini plainly knew it.

In fact, he may have felt the same way himself. In his drawing of the ‚ÄúNativity‚ÄĚ in pen and brown ink, the rustic barnyard scene of the little family attended by a donkey, cow and shepherds is fenced off from the Italian countryside, itself backed by a distant view on the horizon of a fantastic urban skyline that strings together fanciful towers, domes and parapets.

The city is a virtual Oz. It rises beyond a luxuriant field, a setting before which a miracle takes place. In Bellini’s nativity, the Venetian Renaissance is being born.

‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶ ‚ô¶

‚ÄėGiovanni Bellini: Landscapes of Faith in Renaissance Venice‚Äô

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Through Jan. 14; closed Mondays

Info: (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu

Twitter: @KnightLAT

MORE ART NEWS AND REVIEWS:

Why MacArthur fellowships matter more in the era of Trump

In Gary Simmons' hands, classic film titles ooze with racial history

Billy Al Bengston 'Dento' paintings at Parrasch Heijnen

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.