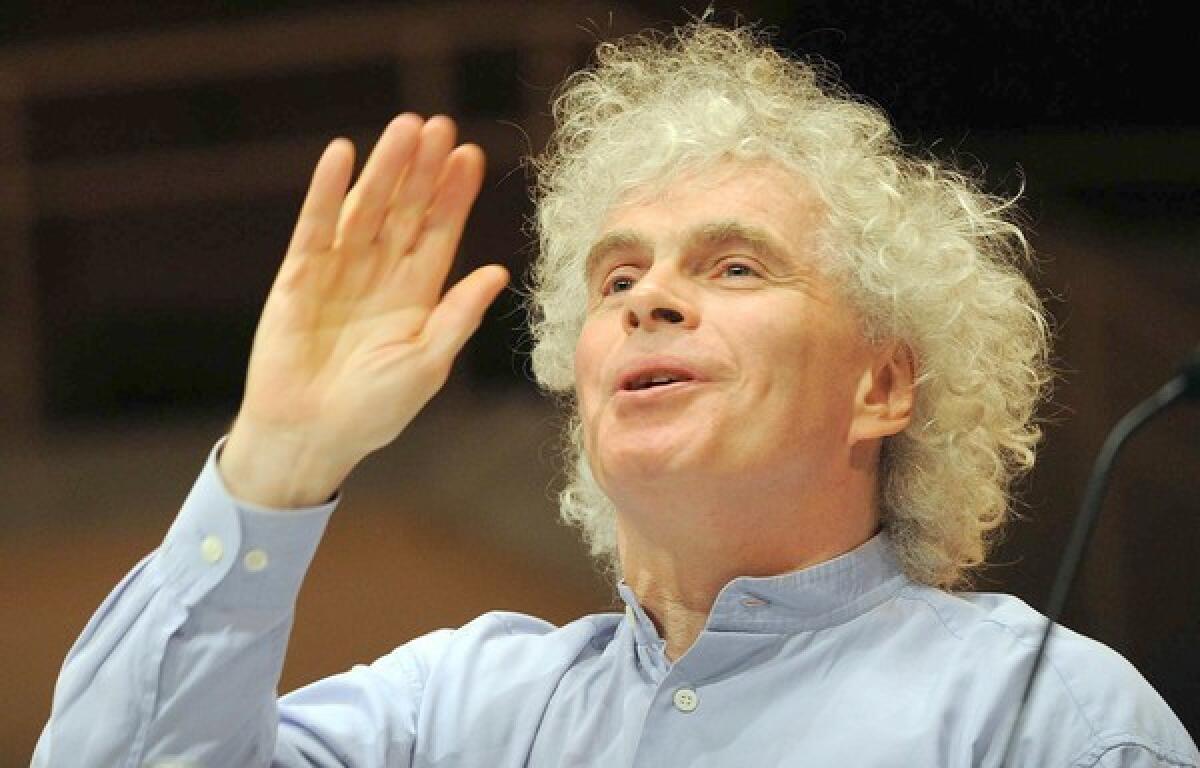

Simon Rattle wins over the Berlin Phil and its fans

In April 1989, the glamorously autocratic Herbert von Karajan resigned from his post as music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, the West German ensemble he had led for 35 years and made into the most brilliant orchestra the world had ever known. In July, he died. On Nov. 9, the Berlin Wall came down.

Then, on Christmas Day, Leonard Bernstein, Karajan’s old rival, summoned orchestra members from Munich, Dresden, Leningrad, Paris and New York to the once and future capital of Germany for the official concert celebrating the fall of the wall -- a historic performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Had the mighty Berlin Philharmonic fallen as well?

It hadn’t. In fact, what had once been the orchestra of the Third Reich (Karajan once was a member of the Nazi party) was liberated.

The Berlin Philharmonic, which will appear at the Walt Disney Concert Hall in programs of Brahms and Schoenberg on Monday and Tuesday nights conducted by Simon Rattle, is still an orchestra of captivating virtuosity, its sound silken and dazzling. But Berlin is a radically different city than it was 20 years ago, and the Philharmonic is just as radically different an orchestra.

Like a city rebuilt with the help of international architects, the once Aryan orchestra now boasts musicians representing 40 nationalities. And like Berlin in the two decades since German reunification, its leading orchestra is feisty and cutting edge -- yet deep down doggedly traditional.

The challenge, then, for the Berlin Philharmonic is not only to remain the symbol of the city (its concert hall, the Philharmonie, stands in what is now the center of modern Berlin) but also to be a model for cultural and social unification in an anxious metropolis, where old and new, German and foreign influences, excitingly if also tensely coexist.

Schools and prisons

That’s where Rattle comes in. When he became the orchestra’s principal conductor and artistic director in 2002, after 18 years with the City of Birmingham Symphony in England, he found a city that was fiscally bankrupt but artistically vibrant and an orchestra that had had a rocky but not undistinguished 13 years under Claudio Abbado. The Italian conductor had begun a modernization project, and now the organization thought it might be ready for a big musical adventure.

Adventure it got -- and perhaps more than the players, audiences and critics bargained for. Welcomed as “Sunny Sir Simon,” Rattle took this elite orchestra places it had never dreamed of setting foot -- to schools in poor immigrant neighborhoods and to maximum security prisons. After a while, the German press began to turn on Rattle, finding Sunny Sir Simon’s conducting all empty smiles.

“It’s been an interesting journey,” Rattle said last week over the phone in Berlin after a rehearsal for his U.S. tour, which began in New York. “Slowly and surely we have come together through honeymoons and the opposite. I remember Karajan said that with an orchestra like this the first five or 10 years are tradition. I didn’t quite believe him. But after what has sometimes felt like moving at the speed of tectonic plates, or [British Prime Minister] Gordon Brown’s smile, we now have a tradition to build on.”

Once more the darling of Berlin, Rattle credits at least some of the turnaround to Brahms. A year ago, he conducted a cycle of the four symphonies, music that has been in the orchestra’s collective psyche since its founding in 1882, to high acclaim. The symphonies were recorded live and have just been released as a box set on EMI Classics.

The playing is, as it always is with this orchestra, superb. And it is easy to see why Rattle finally won over his doubters. There is something for everyone. The orchestral sound is powerful and protein rich but also graceful. This is Brahms with vitality and also an autumnal glow, Brahms that is heavy and serious but not oppressive, Olympian Brahms but not unapproachable Brahms.

The set is, in the best sense, Berlin Brahms, and Berlin no longer doubts that it wants more. Last month, the self-governing orchestra extended Rattle’s contract through 2018.

But Rattle is quick to point out that the Berlin tradition he has revitalized isn’t quite so clear cut as people seem to think. For one thing, he oversees an increasingly young and international orchestra. Players, Rattle says, have been hired without ever having played in an orchestra. And even those who have, including principals, have arrived without having ever played certain key works, such as Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

The orchestra’s DNA, somehow, gets transplanted into the new players but not without the occasional genetic mutation. “Sometimes we have to search for that style,” Rattle says, “because there are actually many ideas about what the orchestra’s style had been. This is a listening orchestra.

“Many American orchestras will say, ‘Just give us a clear beat.’ But that doesn’t work here. You must find a way to invite them to play, and I learned to be a lot freer and less controlling. Now that we’re doing these Brahms symphonies again for the tour, we’re already rethinking them. The process never stops.”

What has also made a difference is that Rattle is now part of his community. At first, he split his time between England and Germany and didn’t speak German. But now he has settled in Berlin with his third wife, Czech mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kozená, and their two young sons.

Collaboration

Rattle has also become evangelical about spreading the word across much wider expanses, with his Philharmonic’s digital concert hall. This is the first orchestra to broadcast all its concerts in high-definition video and sound on its website pay per view.

Although he hasn’t conducted in Los Angeles -- where he served as principal guest conductor of the L.A. Philharmonic from 1981 to 1994 -- since 2003, Rattle says he has been keeping up with the West Coast and particularly with composer John Adams and director Peter Sellars. Berlin was one of the commissioners of “The Flowering Tree,” the most recent Adams-Sellars operatic collaboration. Subsequently, Rattle has invited Sellars to “ritualize” Bach’s “St. Matthew” Passion for performances at the Salzburg Easter Festival and then at the Philharmonie in Berlin.

“During a choral rehearsal for ‘Flowering Tree,’ ” Rattle recalls, “Peter found it terribly important to tell the chorus what it felt like when a parent is forced to beat a child,” which is a scene in the opera. “When I walked in, Peter was in tears, and so was the chorus. At that point, we all knew he had to come back.”

What he wants from Sellars for the Bach is not a staging but internalized context. The soloists and chorus will sing from memory so they will be free to move around, but there won’t be sets or costumes and, Rattle says, he nixed Sellars’ request for dancers. The idea is simply to spend a couple of months going as deeply as possible into a profound work of art.

Rattle was an early champion of Gustavo Dudamel, the L.A. Philharmonic’s new music director, and Dudamel apprenticed briefly in Berlin with Rattle.

“But Gustavo hardly stops whirling long enough for me to claim being mentor,” Rattle says. “He’s physically and musical guts-wise, one of the most complete conductors I’ve ever seen.

“I pray,” he concludes, “that he can keep growing.” In that regard, Rattle’s Berlin Philharmonic, where Dudamel is now a regular guest, may also be a model.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.