Review: LACMAâs new hunk âLevitated Massâ has some substance

On Sunday morning, artist Michael Heizerâs eagerly anticipated environmental sculpture, âLevitated Mass,â finally opens to the public at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. At an 11 a.m. ceremony, ribbons will be cut, speeches made, the artist and donors to the $10-million project thanked.

It will also be a moment to rein in expectations. âLevitated Massâ is a good sculpture if not a great one.

Commissioning new art always courts risk. All a museum can do is place its faith in a gifted artist like Heizer and use its institutional clout to help clear the way.

This project encountered an unexpected hurdle. Celebratory hubbub and international media noise accompanied the sculptureâs centerpiece â a 340-ton stone megalith â on its remarkable spring journey from a quarry outside Riverside to mid-city L.A.

Huge advance publicity set up a love-it-or-hate-it anticipation for either a masterpiece or a fiasco. But this work is neither. The sober, even solemn finished sculpture at LACMA reminds us that our headlong tendency to divide a world of rich, granular grays into stark black-or-white is its own form of ruin.

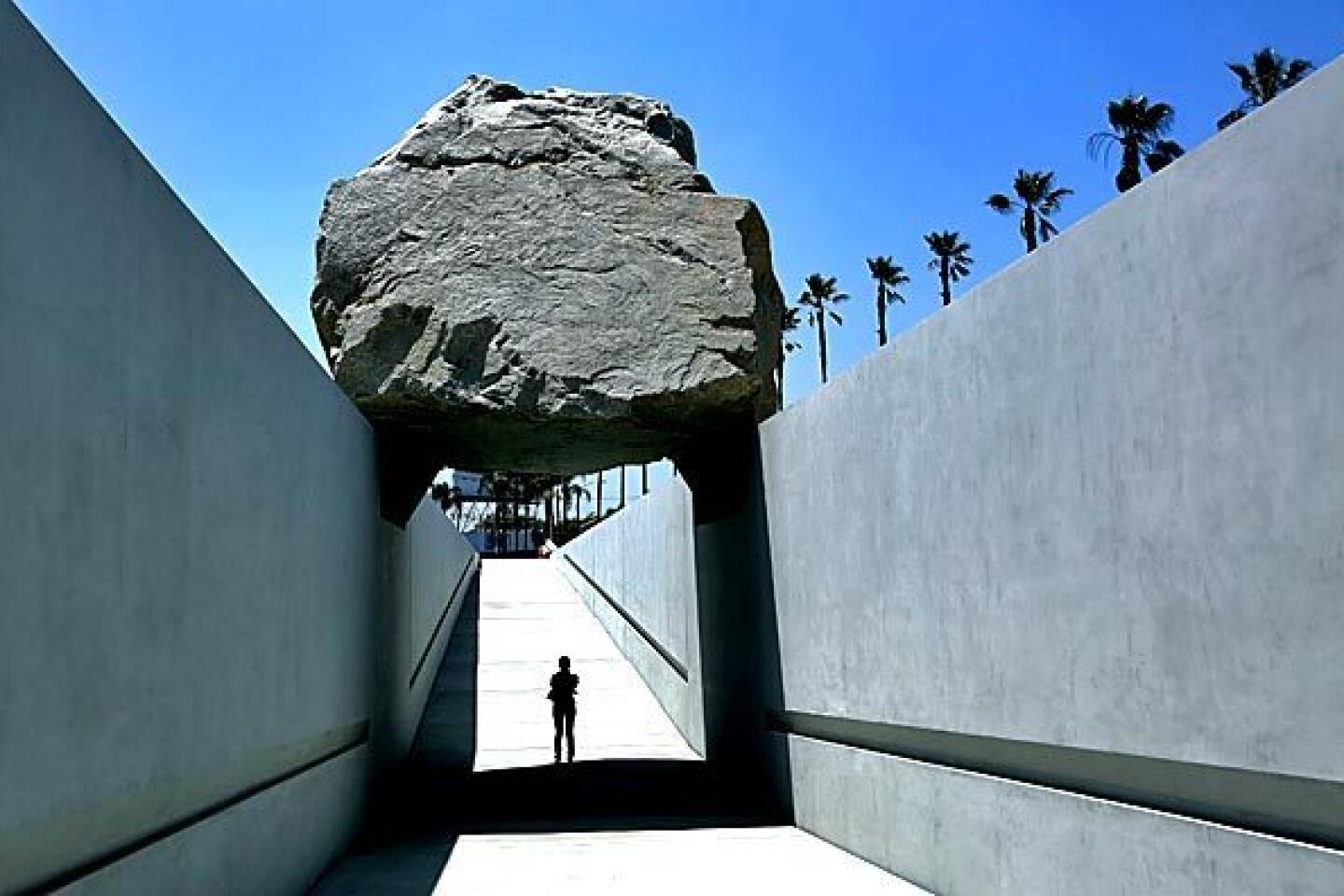

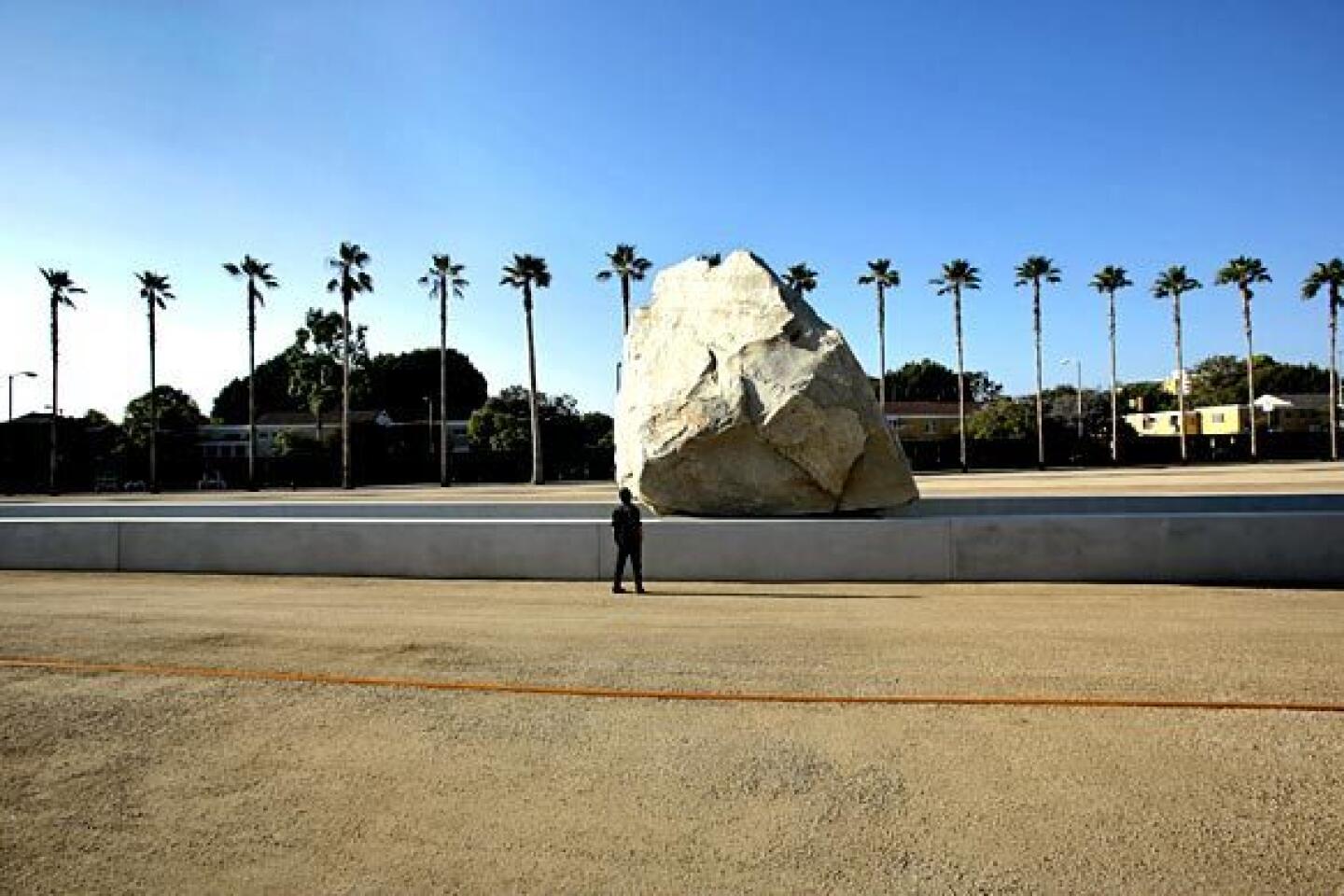

âLevitated Massâ is a piece of isolated desert mystery cut into a dense urban setting thatâs home to nearly 10 million people. A water-hungry lawn north of LACMAâs Resnick Pavilion was torn up and replaced by a dry, sun-blasted expanse of decomposed granite. A notched gray channel of polished concrete slices 456 feet across the empty field, set at a slight angle between the pavilion and 6th Street. Like a walk-in version of an alien landscape painting by Surrealist Yves Tanguy, quiet dynamism inflects a decidedly sepulchral scene.

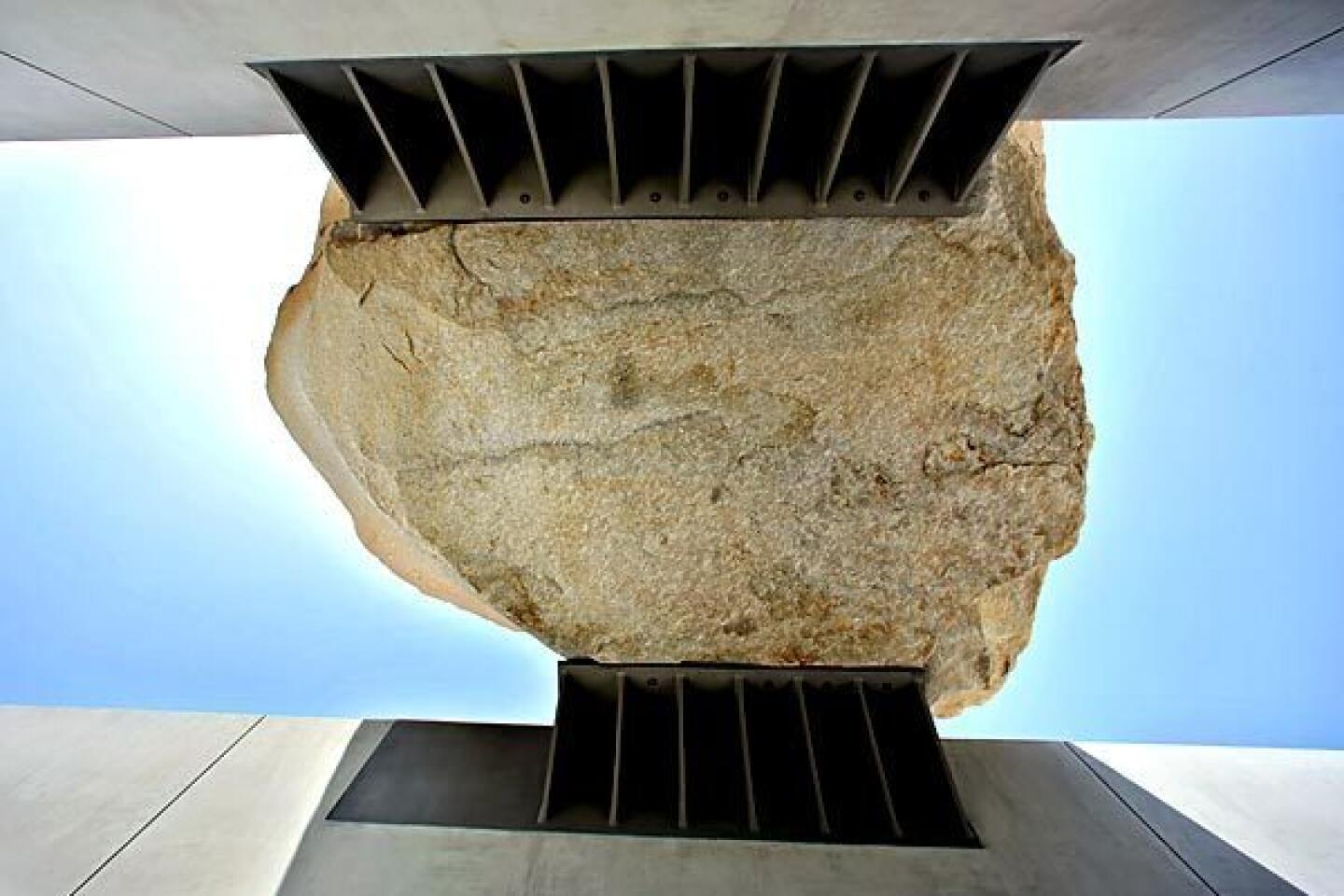

The channel, descending to a depth of 15 feet, is a two-rail pedestal for the huge stone megalith, which is bolted to steel shelves affixed to the center of each side wall. The path slopes gently down, inviting passage, until a visitor stands below ground with the immense boulder spanning the space overhead and blocking out the sun. Surrounding landscapes fall away.

Arrival at the bottom is momentarily disconcerting. After all, how often does one see the underside of a 680,000-pound rock? The bemusement soon dissipates, though, replaced by simple curiosity about the constructionâs elaborate engineering.

The pyramidal stone has been cut across the bottom to fit those heavily ribbed steel shelves. Thick bolts anchor it in place, conforming to essential demands for earthquake safety. Slits at each side of the concrete floor provide drainage for inevitable rains, as do drains hidden beneath the surrounding decomposed-granite field.

Returning to the surface, other details emerge. The long channel is encircled by a lozenge-shaped line of Cor-Ten steel, embedded in the earth and rusting to a velvety brown. Decomposed granite, sloping gently toward the slot, seems like a forecast of the megalithâs slowly decaying future, reaching forward to its destiny thousands of years hence. The surrounding cityscape suddenly appears vain and fragile, the sculptureâs most affecting feature.

Sophisticated industrial technology fuses abstract 1960s Minimalist sculpture with an ancient monumental form. (Heizerâs late father, a noted anthropologist and archaeologist, was collaborating on a book about the transport of massive stones in antiquity when he died in 1979.)

Megaliths are large stone markers, used by diverse civilizations over millenniums to create ritual spaces, mark geographic territory or identify a grave site.

Look at Caspar David Friedrichâs painting âA Walk at Dusk,â circa 1830-35, a bleak and wintry little masterpiece at theJ. Paul Getty Museum. The crepuscular landscape shows a man contemplating an ancient megalithic tomb. With its oblique message of mortality, natureâs eternal cycles are encoded in a misty crescent moon.

âLevitated Massâ isnât exactly Stonehenge or Half Dome. Itâs not even Eagle Rock. As monoliths go, the stone seems rather modest.

Heizer, 67, conceived the work 43 years ago. It was an early manifestation of Land art, an international movement among artists to work directly with the landscape as material, rather than representing it in paintings or depositing discreet sculptures on it. (Currently a good survey of the movement, âEnds of the Earth: Land Art to 1974,â is at the Museum of Contemporary Art, although the reclusive Heizer declined to participate.) The specific site of âLevitated Massâ today resonates in ways he couldnât have considered then.

The brooding sculptural ensemble marks time both cultural and geological. Adjacent to an urban art museum, repository for the relics of civilizations gone by, itâs also next to the La Brea Tar Pits, resting place for prehistoric bones sunken into the primordial goo. Unavoidably, it calls for contemplation of our transient place in the larger scheme of things.

It will also surely beckon skateboarders eager to navigate its sloping ramp. Posted museum guards will likely thwart that urge.

Last March, the huge granite boulder slated to become the workâs centerpiece took Southern California by surprise â and by storm. Traveling at night along a circuitous, 105-mile path across the suburban sprawl, the rock crawled through four counties and 22 cities suspended in an industrial sling on a specially built, 200-foot-long transporter with 88 pairs of wheels. In the process, it became an unlikely media celebrity.

The $10-million cost for the elaborate construction project primed the rockâs notoriety. Americans might be generally indifferent to art, but money gets them worked up.

The trip had been delayed for months by nervous jurisdictions along the route, but once it got going the cameras â from corporate television stations to individual cellphones â quickly followed. So did legions of groupies, gawkers and local street fairs, planned and impromptu, all surfing the massive wave of publicity. A thousand metaphors bloomed.

The rock was rolling. A rolling stone doesnât gather moss, but it could get social media like Facebook and Twitter humming. A rock star was born.

Now, that catalytic rocker stands transformed into a motionless, contemplative rock garden. If a megalith is a marker, Heizerâs âLevitated Massâ has what passes today for civilization squarely in its pensive sites. Certainly there is goodness in that.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.