- Share via

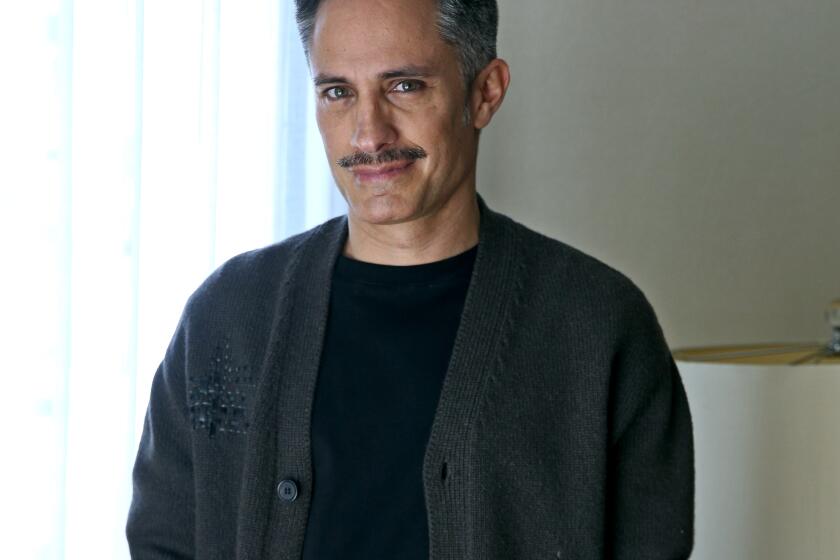

When Mexican cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, or Chivo, as he is affectionately nicknamed, first read the screenplay for “Disclaimer” by his lifelong friend and director Alfonso Cuarón, he was struck by the intricate descriptions of the changing visual mood as the story progresses.

“This is the first time where the lighting is so detailed in his script,” Lubezki, 59, says on the phone speaking in English. “Alfonso describes the color of the sky in the morning, the height of the sun, the angle of the light entering the kitchen. It was so beautifully written.”

Even after more than 40 years of friendship and fruitful artistic confrontations, Cuarón and Lubezki are still inspiring, and sometimes exasperating, each other. Together, via the miracle of cinema, they have imagined and materialized heart-pulsing images in a dystopian future, a lyrical road trip through southern Mexico and even an outer space adventure.

Cuarón, 62, refers to their affinity as “telepathic.” Between them, there’s a common understating of the elements within the frame, as well as a mutual concern for crafting images where any stylistic choice is secondary to the substance of what they communicate.

“There are many cinematographers whose work is beautiful, but there isn’t an organicity to the cinematic language in what they do,” Cuarón says. “But for Chivo, aesthetics exist only in function of the cinematic language. He understands that in a radical, even religious way.”

The Apple TV+ limited series “Disclaimer,” premiering Friday, reunites the two Oscar winners for the first time since 2013’s astronaut drama “Gravity,” one of their many shared projects since the 1980s.

“The collaboration with Chivo begins from the moment I have the idea, and then throughout the writing process I continue discussing ideas with him,” Cuarón tells me over a video call in Spanish from the Toronto International Film Festival, where “Disclaimer” screened last month.

At the center of “Disclaimer” is acclaimed documentary filmmaker Catherine Ravenscroft (Cate Blanchett), whose hidden past has reemerged to haunt her in the form of a recently published book, as well as in the machinations of a man named Stephen Brigstocke (Kevin Kline) seeking retribution. (Young Catherine is played by Leila George in the series.)

Kevin Kline as Stephen Brigstocke in “Disclaimer.” (Apple)

Cate Blanchett as Catherine Ravenscroft in “Disclaimer.” (Apple)

Cuarón received the 2015 novel that the series is based on from author Renée Knight about a decade ago as a galley proof. While he found it thematically rich, it was the use of narration in different grammatical persons to express distinct perspectives that most intrigued him.

However, at the onset, Cuarón was unsure about how to turn the original material into a conventional film. It was only several years later, following his semiautobiographical film “Roma,” that he realized how he could adapt it. He revisited miniseries such as Ingmar Bergman’s 1973 six-part series “Scenes From a Marriage,” Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1980 14-part series “Berlin Alexanderplatz” and the more recent “Li’l Quinquin,” Bruno Dumont’s 2014 film that was released as a four-part miniseries, where each of the renowned directors told a longer-format story but still retained the integrity of a singular artistic voice throughout.

Lubezki recalls Cuarón explaining to him that “Disclaimer” would exist in episodic form.

“Alfonso said, ‘It’s really a film, but they may release it as a series, and I don’t know if you mind that it’s not going to be released in theaters.’ I said, ‘I don’t care,’” Lubezki recalls. “I wanted to do it, especially after not being able to do ‘Roma.’ It really hurt me that I wasn’t there with him.”

Throughout the making of this “long movie,” neither Cuarón nor Lubezki ever considered it television. Cuarón wrote one screenplay with more than 300 pages, and later divided that into chapters based on the piece’s dramatic modulations.

“It’s the vision of one director,” Lubezki says. “He directed all the chapters — he will kill me if I call them episodes — which almost killed him because it was enormous.”

“There are four fundamental narratives in ‘Disclaimer,’” Cuarón explains. “There are three voice-overs: one in the first person, one in the second person and one in the third person. And then there is the narrative that happens in the book that’s published within the story. I told Chivo that each of these narratives should have a unique filmic language.”

For the first-person narrative, which follows Kline’s character on a mission to inflict pain on Catherine, the person he blames for his misfortunes — the loss of his family and a job that he’s grown increasingly despondent in — we see the world directly through his eyes, whether it’s a sandwich he eats in his increasingly filthy kitchen or the photographs he finds tucked in his dead wife’s purse, discovered under a wardrobe. For Blanchett’s part, told in the second person, the approach is more distant, as if observing her clinically from a distance.

“The second-person narrative has rarely been used in both film and literature — almost all narratives are told in the first or third person,” Cuarón says. He says he first experienced the second-person narrative employed onscreen in the 1974 French film “The Man Who Sleeps” co-directed by Bernard Queysanne and novelist Georges Perec based on the latter’s novel.

For comparison, the narration that actor Daniel Gimenez Cacho does in Cuarón’s “Y Tu Mamá También” is in the third person. He is telling the audience about the two friends.

Gael García Bernal in “Cassandro” is yet another example of the Mexican actor’s versatility. From his feature debut in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s “Amores Perros,” he has played roles that have earned him praise in his native Mexico and abroad.

“The narrative lines of my other films are quite simple, clear and linear, and there is not much dialogue in them,” Cuarón explains. “[‘Disclaimer’] has many dramatic lines. It’s a narrative clockwork where dialogue also has a more important role.”

And that’s why Cuarón thought it imperative for his writing to highlight the visual details of the drama, which Lubezki says stunned him upon first reading the adaptation.

Realizing this would be a massive undertaking, Lubezki became worried about the project’s demands. Luckily the two are on the same frequency, and Cuarón agreed it would be prudent to hire another cinematographer.

“When he said, ‘Who do you think this person should be?’ I said, ‘It should be Bruno [Delbonnel],’ and Alfonso said, ‘I had thought about him too,’” Lubezki says.

Delbonnel (who shot the beloved French classic “Amélie”) was tasked mostly with shooting the sections told in the third person, which pertain to people in Catherine’s life, such as her husband, Robert (Sacha Baron Cohen), whose scenes in the aftermath of learning a secret are filmed with a handheld camera, even using zooms to capture the anxiety he feels with visual immediacy.

On the other hand, Lubezki and Cuarón decided that they would present Blanchett’s storyline in real time. It entailed longer takes without any additional coverage and Blanchett’s movements dictating where Lubezki’s camera went in a sort of choreography.

“Often what we were doing was learning to dance with Cate,” says Cuarón, who believes both Blanchett’s and Lubezki’s contributions to “Disclaimer” were integral in shaping it. Both are executive producers on the project.

“His credit as executive producer is not just a reward,” Cuarón says. “The collaboration with Chivo is from start to finish, it is not only in the image. It goes beyond that.”

Cuarón and Lubezki first became friends after frequenting the same art-house cinema, the CUC (Centro Universitario Cultural), in the south of Mexico City, where every weekend, films by international masters such as Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa or Federico Fellini would screen.

“We always ran into each other there because it was also the meeting place for teenagers to go out and party that same night,” Cuarón recalls. “On many occasions I ended up talking with Chivo for hours at a party about what we had just seen at the cinema. We were the geeks in the corner of the room talking about movies.”

Lubezki remembers Cuarón holding court outside the CUC. “Many times, coming out of the theater I would see Cuarón surrounded by beautiful girls talking about things like the use of color in [Michelangelo] Antonioni’s movies,” he says. The younger Lubezki admired Cuarón, who represented a source of culture.

Cuarón was already a student at CUEC (Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos) when Lubezki was admitted into the competitive film school. At that point, Lubezki had already tried his hand at still photography, and his natural ability for thinking outside the box surprised Cuarón, who back then often shot projects for fellow students.

“I saw the first exercise he did on Super 8 film stock and at that moment I said to myself, ‘What am I doing? Chivo is a real cinematographer,’” Cuarón remembers. “Already in that early school exercise, he was transgressing all the principles that we knew.”

These days, Lubezki’s fascination with light continues to define how he relates to the world. “You could be having dinner with him in a restaurant where there is a little lamp or a candle on the table, and he doesn’t even realize it anymore but he subtly starts to adjust the light,” Cuarón tells me. Signs of where Lubezki’s passion lay were evident to Cuarón as early as the days when he would bring him on jobs as a second assistant director.

“I can tell you that Chivo was the worst second assistant director that has ever existed in history, because he absolutely didn’t care about his job as assistant director, le valía madres,” Cuarón says. “He was more focused on the light.”

They both agree that with age, the visceral edge of their professional arguments has (mostly) mellowed out since their time making “La Hora Marcada,” a Mexican horror anthology series, in the late 1980s. They never thought of it as “making TV,” but remember it as a crucial training ground to learn in a professional setting.

“When we work together and I feel that something is not right or that it could be better, there’s this whole Mexican confrontational thing between us of, ‘Cabrón, come on,’ but it’s all to try to make the best film possible,” Lubezki says.

“If we have a disagreement and he tells me, ‘You’re not going to like it,’ I know I’m not going to like it,” Cuarón says. “And if I tell him, ‘That’s not going to work,’ he knows that that’s not going to work. And it’s not that it doesn’t work technically, but creatively it’s not going to work. We immediately stop and start to see what the other option is.”

Based on their memories, the most contentious of their collaborations might be the futuristic thriller “Children of Men.” Cuarón recalls threatening to shoot a scene inside a vehicle using a green screen if Lubezki couldn’t figure out a way to do it without cuts. And Lubezki thinks of another complex long take in the film that involved tanks and a shootout where fake blood got on the camera’s lens and he decided to keep on shooting, going against Cuarón’s orders. Lubezki’s risky move paid off because the end result was exhilarating. “That’s one of the shots he was lucky that I was close to the camera and that we didn’t stop,” the cinematographer adds.

Alfonso Cuarón and Emmanuel Lubezki filmed ‘Children’s’ tough chase scene without breaking their rules.

To explain the tug-of-war that happens between him and Cuarón when they work together, Lubezki refers to a story that the late actor Peter O’Toole once shared. O’Toole had sent a leather jacket to the dry cleaners. When it returned, it had a note attached. It was the establishment apologizing for not being able to leave it spotless. “It distresses us to return work which is not perfect,” the note read.

Therein lies the Mexican duo’s artistic ethos.

“It distresses us, [Alfonso and I], to create work which is not perfect, and that is horrendous because it means that there’s pain when you are working because perfection is probably impossible to reach,” Lubezki says. “You are attempting to make it as perfect as possible, knowing that it’s probably impossible, but you don’t give up.”

In that pursuit of the unattainable, the two amigos often have achieved cinematic brilliance together.

“Chivo is an alchemist. He challenges creative and technological limitations,” says Cuarón about his closest partner behind the camera.

“Alfonso is the most important film teacher in my life,” says Lubezki, reinforcing their bond. “And he is one of the great directors of our time.”

“Disclaimer” didn’t rekindle such mutual devotion; it simply presented a new opportunity for them to profess it onscreen.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.