The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyoneâs talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

SPECIAL REPORT

Hollywood's Latino Culture Gap

Times journalists examine the complicated history of Latinos in Hollywood and the actions being taken to increase their representation, which remains stubbornly low. FULL COVERAGE

There is a narratively insignificant design detail in the 2019 sci-fi flick âAlita: Battle Angel,â directed by Robert Rodriguez, that Iâve always admired.

As our cyborg hero, Alita (Rosa Salazar), challenges nemesis Zapan (Ed Skrein) at a cantina-style establishment on a future Earth, a viewer might notice that the enemyâs back is adorned with what appears to be a replica of the so-called Aztec sun stone. (Youâve seen the image on T-shirts, ponchos and murals; the original sits in the most prominent spot inside Mexicoâs national anthropology museum in Mexico City.)

The detail doesnât matter expressly to the story, but it is a creative flair that as a viewer I somehow canât ever forget. Call it the Robert Rodriguez touch.

Rodriguez stories, whether set in a sci-fi fantasy world or a border town in Texas, are full of such cultural signals. When taken together, they make the Rodriguez viewing experience measurably richer for anyone who has even the slightest point of reference to pan-Mexican identity and culture. And these days in the U.S., honestly, who doesnât?

I shared this thought with Rodriguez â Zapanâs back, the little details â as we sat down for dinner one recent night. He smiled knowingly.

âI think thatâs why I gravitate toward making movies that are very enjoyable to anybody, but for those who are Latin, they go, âSâ, thatâs us,ââ Rodriguez said. âWhen I did âDesperado,â I wanted people to just enjoy the movie, but for those who are Latin, it would mean so much more to them. The same with âSpy Kids,â the same with âMachete.ââ

âActing wasnât new to me. Iâd acted to survive my childhood,â writes Danny Trejo in his new memoir. He talks with The Times about his incredible life.

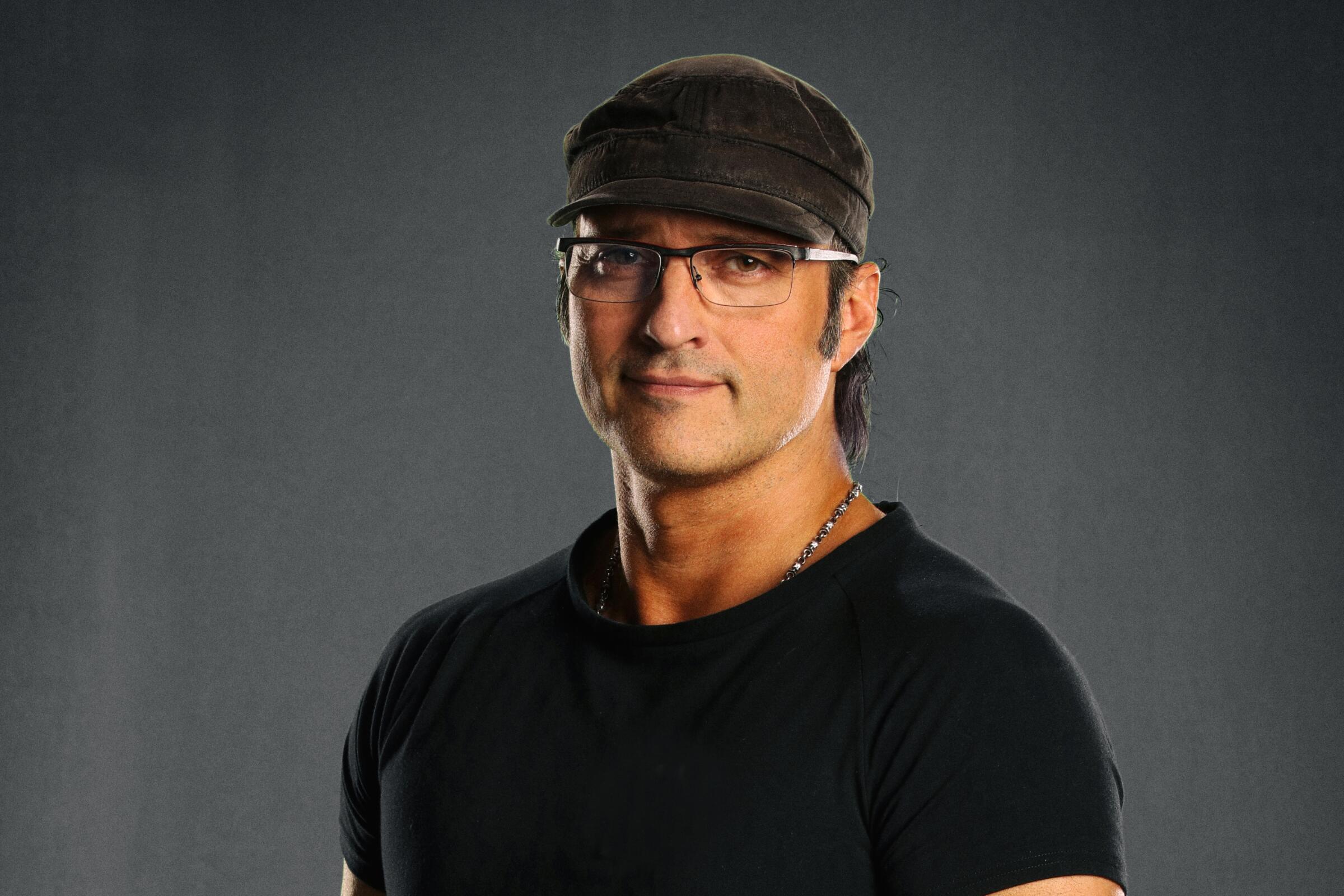

Rodriguez, a native of San Antonio, Texas, manages to reach broad audiences by the appeal of his specificity. In his case, heâs built a pop-culture canon in several genres that is constantly referencing Latinidad, and even more precisely, expressions of contemporary Mexican-ness or, if you will, Tejano-ness.

Now, the filmmaker, 53, is bringing the Rodriguez touch to a new venture, which will officially be announced Thursday: a two-year first-look deal heâs signed with HBO Max and HBO, joining his Austin, Texas-based Troublemaker Studios and his son Racer Rodriguez in a key executive role. The announcement comes less than a week after word emerged of a separate deal to revive Rodriguezâs El Rey Network, which stopped operating as a cable channel in December but is relaunching as a free streaming service.

âRobert Rodriguez and the team at Troublemaker Studios have created some of the most compelling projects in recent memory, pushing the boundaries of genre storytelling with humor and one-of-a-kind visuals,â Sarah Aubrey, head of original content at HBO Max, said to The Times. âIt is such a privilege and joy to work with Robert and his incredibly talented kids. Together, they bring a fresh perspective to genre storytelling that has specificity, originality and heart.â

âThey have Latin executives, and theyâre really into it,â Rodriguez said of his new HBO partnership. âTwo years gives us enough runway, but they also need product. And thatâs the content creatorâs dream, that you have partners that need and want content, and they want it to be diverse. This is the Gold Rush era, and it just feels amazing that itâs all happening now.â

Rodriguez is tall and striking, squeezing into a booth at a discreet neo-Mexican restaurant in the corporate-park section of El Segundo. Heâs been in town intermittently and quietly, finishing work on the upcoming âBook of Boba Fett,â the Fett spinoff to âThe Mandalorian,â on Disney +.

In Season 2 of âThe Mandalorian,â Rodriguez directed âThe Tragedy,â the episode that brought back the beloved bounty hunter from the original âStar Warsâ film series. According to a documentary about âThe Mandalorianâ on Disney+, Rodriguez managed to persuade series creator Jon Favreau to let him take a stab at Fett by mocking up scenes at home with Halloween costumes and action figures.

Rodriguez said he was sworn to silence on his work in the new series, which is scheduled to start streaming in December. The director also declined to offer any hints or details on what projects or style of story heâd take to HBO first. Yet the deal with one of the biggest U.S. Latino names in the business presents a good opportunity to reassess how the man got here.

In a conversation ranging from the intricacies of working in the series format to the persistent issue of insufficient Latino representation in mainstream Hollywood, Rodriguez returned again and again to the notion that highly focused world-building in any genre can be âLatinâ in tone or content and also be universally consumed.

âI remember when I was in college, I saw a bunch of John Woo movies that were really big, and youâd walk out of that movie theater wanting to be Chinese. You wanted to be Chow Yun-Fat,â Rodriguez said. âIt was because of how he was portrayed as a hero. I thought, âI want to do that with Hispanics. I want to do that with Mexicans.â

âYou want it to be viewed by everybody, because then youâre part of the international conversation.â

Busting through the barriers that often hinder filmmakers of color, Rodriguez has made blockbusters in genres as disparate as Mexploitation and kids adventure, including not just his âSpy Kidsâ films but also most recently âWe Can Be Heroesâ on Netflix. He effectively changed the course of the Hollywood careers of Salma Hayek, who had been facing barriers for her heavy Mexican accent before being cast in âDesperado,â and iconic tough-guy Danny Trejo, whom he turned into âMachete.â Beyond directing, heâs set out over two decades to build his own entertainment ecosystem behind and in front of the camera, through Troublemaker Studios and El Rey.

Charles Ramirez Berg, a leading academic on Chicano and Latino cinema at the University of Texas at Austin, remembers the young Rodriguez as an aspiring film major there.

âIt got real competitive in the late â80s â I mean real competitive,â Ramirez Berg recalled in a phone interview. âSo he was trying to figure out how to get into the major. Thatâs how we met. He came to my office hours, even though he wasnât my student at the time.â

By 1990, Rodriguez had showed his first short, âBedhead,â which electrified the Texas film community. The film tells the story of a young girl who discovers she has a supernatural talent and features animation by Rodriguez and his longtime collaborator and former wife, producer Elizabeth Avellan.

âIt was incredible, just so much talent, and it was up there on screen in nine minutes,â Ramirez Berg said.

âBedheadâ displays the earliest iteration of the trademark Rodriguez style; his films seem to always leave a viewer feeling a bit off-kilter, but satisfyingly so.

Then came âEl Mariachi,â the Spanish-language narco action thriller Rodriguez made with just a little over $7,000 at age 23. It wowed Sundance, winning the audience award, and got picked up for wide distribution by Columbia Pictures in 1993.

The âEl Mariachiâ phenomenon led to âDesperadoâ (1995) and âOnce Upon a Time in Mexicoâ (2003), which became part of the âRobert Rodriguez Mexico Trilogyâ and set the director on a one-of-a-kind course that still inspires young filmmakers, and which he chronicles in detail in his diary-like memoir, âRebel Without a Crewâ (1995).

A bona-fide maverick in the spirit of Quentin Tarantino and Spike Lee, Rodriguez emerged as a unique figure in that he often shoots, edits and scores his films himself.

Ramirez Berg, who now includes chapters about the filmmakerâs work in his books, referred to his method as âThe gospel of Robert Rodriguez.â

âBasically, itâs âGo out there and make it, and donât make any excuses,ââ Ramirez Berg said. âWhen heâs making a movie, heâs just fluid. Iâve seen him on set, and itâs astonishing, and everyone feels it.â

After his successes in the 1990s and 2000s, Rodriguez took a major career turn â and major gamble â when he pushed his creative energies into launching El Rey, his cable channel aimed at the nebulous and inscrutable U.S. English-Latino market.

Announced in 2012, it started running original programming in 2013. But like other Latino-tinged outfits on linear TV that have made the attempt, El Rey failed to find its audience, or its audience failed to find El Rey; the network succumbed to the cord-cutting era and finally ceased operations in December.

âPeople were cutting cords even back then, we already knew that, and thatâs how we were able to get the network,â Rodriguez said. âBut we thought, âLetâs build a brand, because once you build a brand, you can take that anywhere, so letâs use that cable platform for establishing it. Thatâs what we did.â

Eventually, he concluded: âYou have to sunset the linear and go toward the streaming.â

Thatâs why Rodriguez and co-founders John Fogelman and Cristina Patwa made a deal with niche streamer Cinedigm, which has licensed the El Rey library, including a series titled âThe Directorâs Chair,â in which Rodriguez interviews fellow filmmakers.

Joey Chavez, executive vice president of original programming for drama at HBO Max, described the first-look deal with Rodriguez as a âfull circleâ moment for him. The success of âEl Mariachiâ was an early inspiration for Chavez, an L.A. native and one of a handful of Latino executives in green-lighting positions.

Chavez said Rodriguezâs deal is key in a strategy to more vividly portray Latino experiences on HBOâs platforms, part of an industry-wide push to address lagging representation figures for Latino creatives on major platforms.

âI think one of the things he taught me from early on, inspiring me, is: You also have to do it yourself,â Chavez said of Rodriguez. âYou need people in these positions â as producers, as writers, as executives â to make sure we do better.â

Rodriguez will be joining Hayek, who signed a first-look deal with HBO Max last year with her company Ventanarosa.

Whether itâs his Trejo vehicles âMacheteâ and âMachete Kills,â or even in the âSpy Kidsâ family film franchise, Rodriguez is building worlds meant to appeal to all audiences but just a bit more to members of the Latin American diasporas, normalizing the tiny details and ticks that reflect the amorphous state of being Latino.

âIf you can get a movie out in front of people that can get their attention, well then, that gets the attention of the studios. They want to speak your language now. So if they think they can make money off it, they will,â Rodriguez said. âThereâs no prejudice. Itâs just that theyâre afraid to make a first step in a direction thatâs new.â

His advice to up-and-coming filmmakers is as universal as his own narrative arc.

âDonât play by the rules,â Rodriguez said. âCome up with a way to just jack the system.â

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyoneâs talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.