- Share via

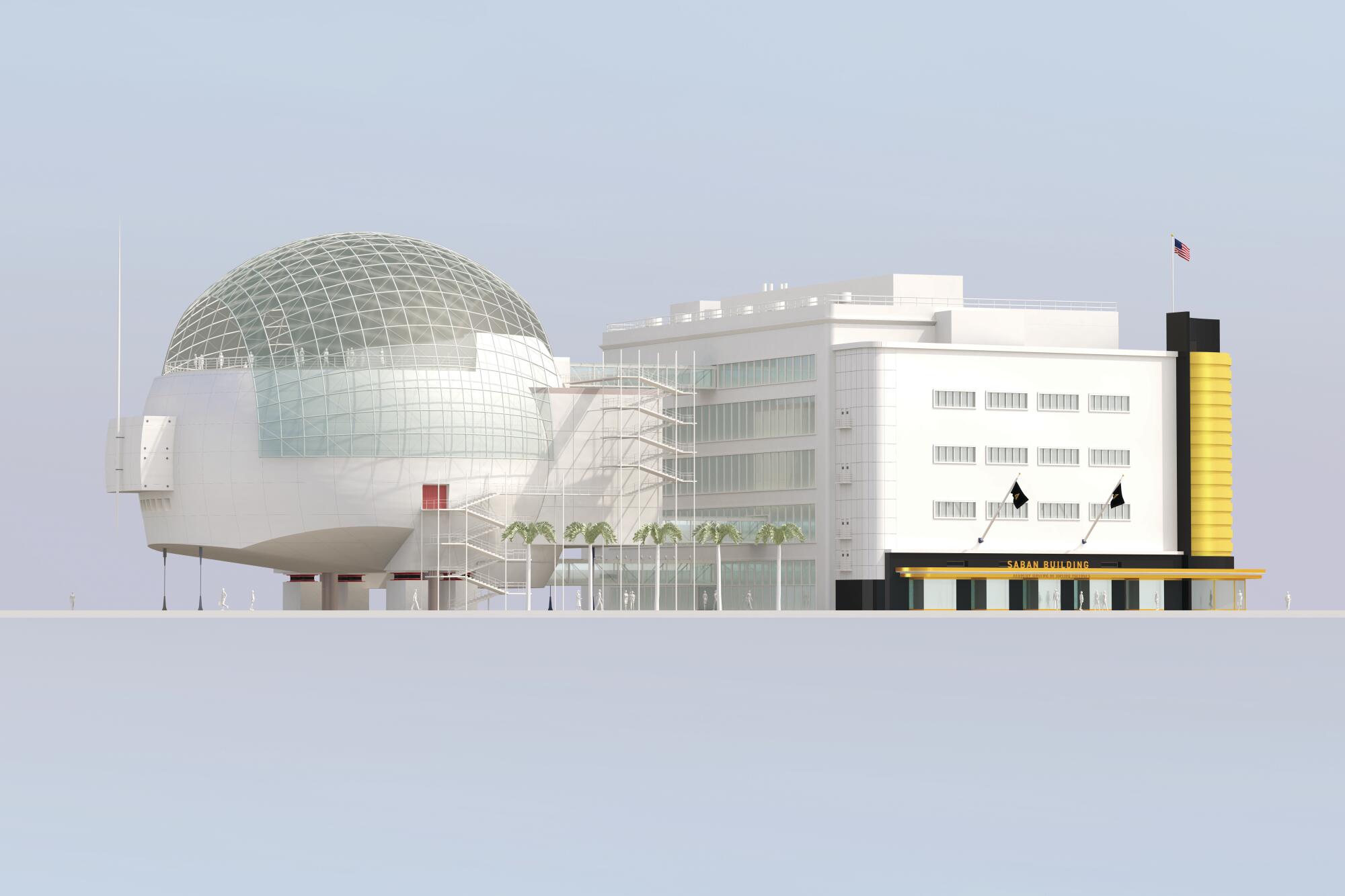

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is an architectural drama in two parts. Act 1 is the 1939 May Co. department store made over into the Saban Building, airy home for exhibition galleries, restaurant, store and intimate below-ground theater. Act 2 is the newly built David Geffen Theater, a glass-topped concrete sphere by starchitect Renzo Piano. Some key details, old and new, with illustrations by Haisam Hussein:

Killer catwalk

The path from the Saban Building to the sphere’s stunning rooftop terrace is a glass bridge just long enough to make an acrophobe‘s palms sweat. Make it across, though, and fab views encompass the Hollywood sign, the La Brea Tar Pits and the big dig of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art next door.

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures has opened as the ultimate celebration of Hollywood history, Oscar lore and today’s movie makers.

• • • • •

Glass dome

Twelve of the sphere’s 1,500 panels of laminated, tempered glass are actually vents that are programmed to lift up and let out hot air. There are 150 sunshades too, each made of PVC-coated fiberglass, that automatically track with the shifting sun overhead. Sensors monitor sun position, brightness, wind and rain. (See separate article on how all that glass gets cleaned.)

• • • • •

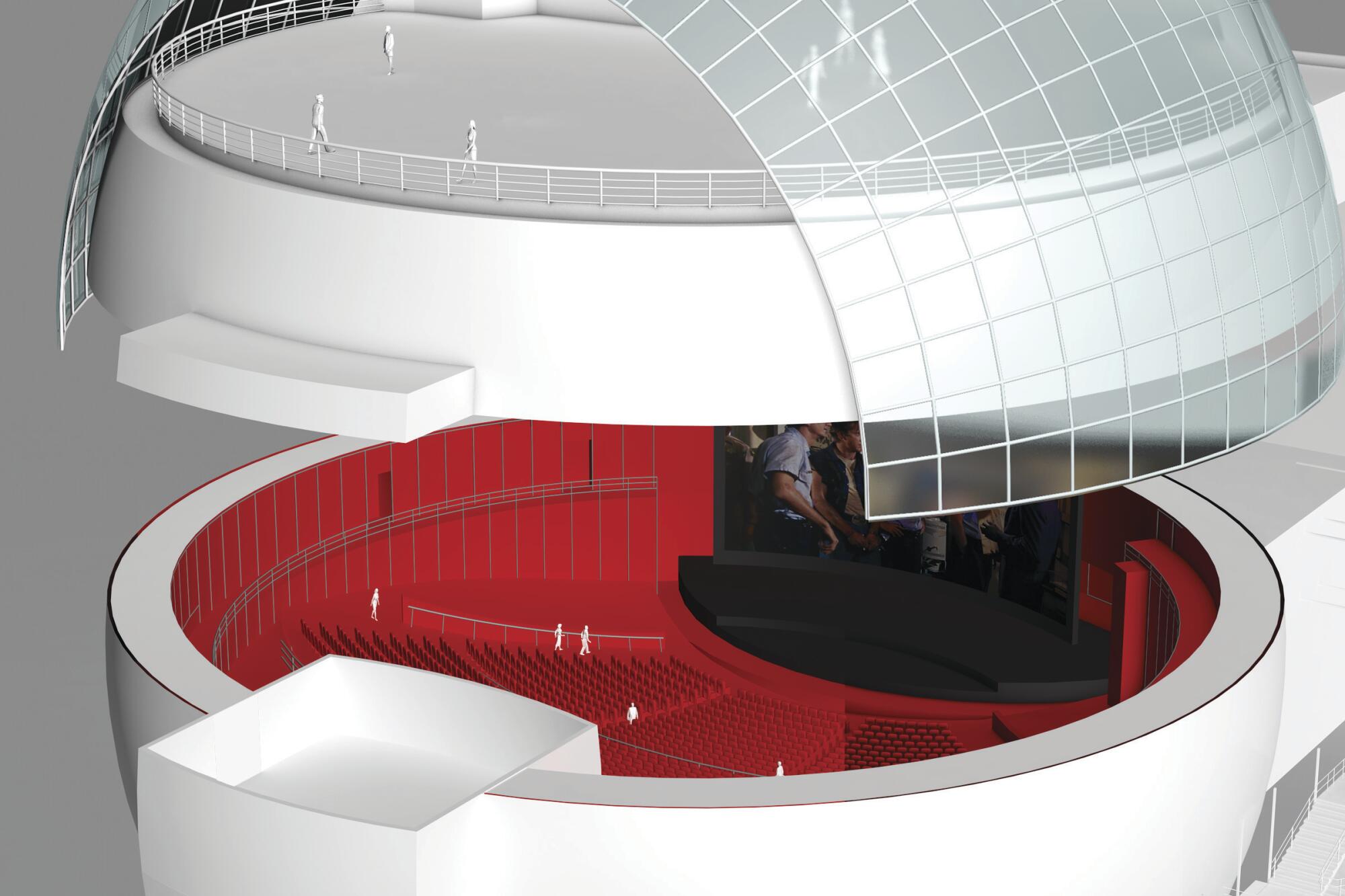

David Geffen Theater

The museum’s centerpiece is a very luxe, very red screening room for 1,000. The entrance to the theater (on another red carpet) is the start of a dramatic procession, each step a visual reveal unto itself. Fronting the screen is a large stage that can accommodate a chamber orchestra for live music. The first screening with musical accompaniment: “The Wizard of Oz.”

• • • • •

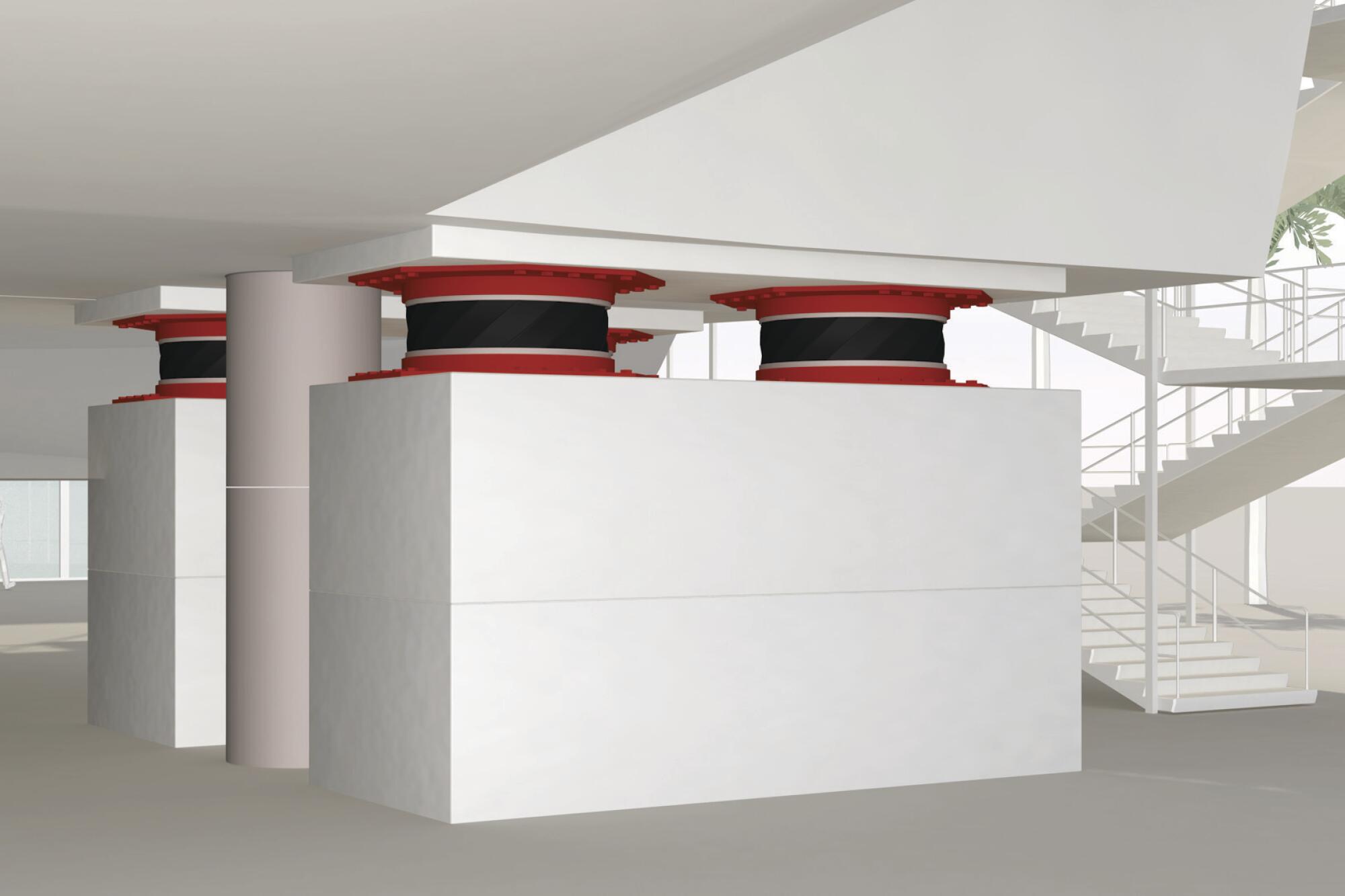

Base isolators

Normally hidden in the guts of the building, they’re exposed here (see separate article). They allow the sphere to remain centered in an earthquake, even if the ground moves up to 30 inches in any direction. The red sheathing matches the accent color of LACMA’s BCAM building next door — also a Renzo Piano Building Workshop project.

• • • • •

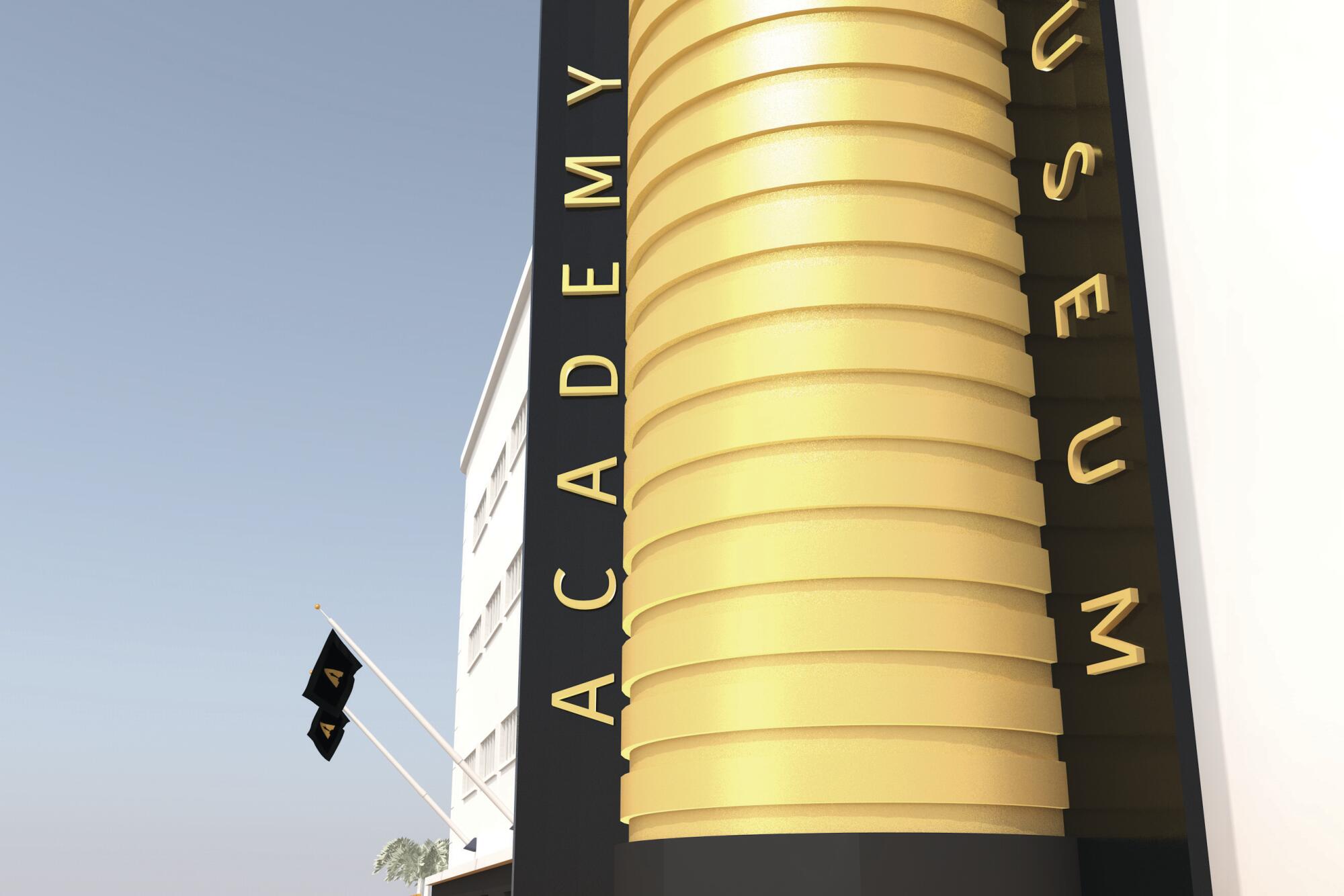

Golden tile

At Fairfax Avenue and Wilshire Boulevard, a tiled corner cylinder remains as the design signature of what the Los Angeles Conservancy calls “the city’s grandest remaining example of Streamline Moderne.” About one-third of 350,000 gold-leaf tiles have been replaced. The museum sourced the substitute tiles from the manufacturer of the originals: Orsoni, a maker of glass and gold mosaics in Venice, Italy, that dates to the 19th century.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.