Review: At the Ford in Hollywood, a revelatory L.A. Phil concert of riveting opposites

- Share via

Arvo Pärt and Julius Eastman, who shared the bill for the Los Angeles Philharmonic chamber music concert at the newly reopened Ford Tuesday night, are the matter and antimatter of Minimalism.

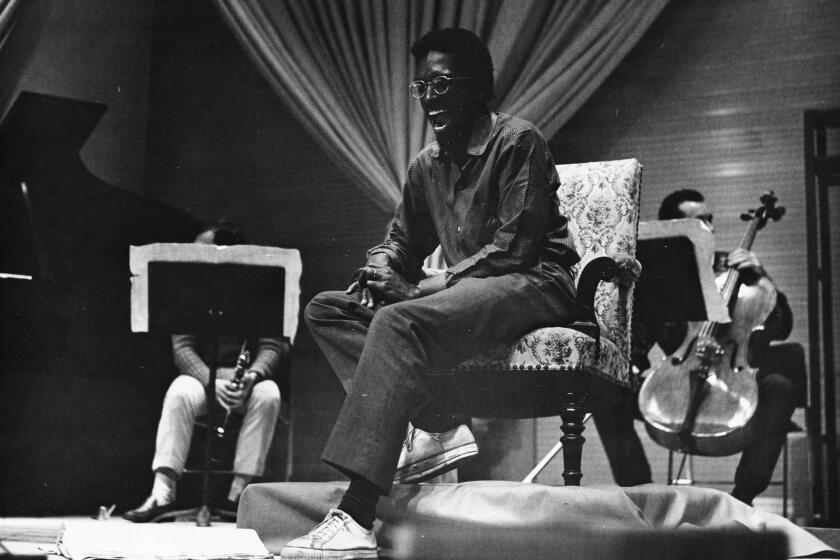

Pärt, the spiritually aesthetic 85-year-old Estonian composer, happens to be the holiest of the Holy Minimalists, as those Eastern European composers who get to consonant essentials are sometimes called. Eastman, the New Yorker from Ithaca who died in 1990 homeless at age 50, paraded himself as the unholiest Minimalist, an outrageous dissonant dissident even in the seemingly accepting new music community.

Pärt is accepted as the epitome of chill. Eastman is hot, hot, hot. Pärt is one of the most performed classical composers of our time. Whether you know it or not, you know his music, so widely has it been imitated and commercially co-opted. The obstinately elusive Eastman is only recently rising out of extreme, self-inflicted obscurity and finding a cult.

What their music shares, conductor Christopher Rountree told the audience in this 1,200-seat jewel of an outdoor theater, is a sense of transcendence. In Pärt’s case, religious transcendence extends beyond our wide universe. For Black and gay composer and vocalist Eastman, transcendence was of the body. I’d take that a step further to say that Pärt offers us an out-of-body experience, whereas Eastman aims gleefully at gut and groin. Pärt’s music is self-control, riveting in its reflection an orderly universe. Eastman is the extreme, riveting opposite.

The concert began with Pärt’s “Spiegel im Spiegel.” The title translates as “Mirror in the Mirror.” You very well have encountered it at as apt accompaniment at weddings and funerals. The score has found its way into film and TV soundtracks and even “The Simpsons.” At the Ford, each ringing note in Joanne Pearce Martin’s piano was like the mirror on a telescope amplifying the light from a star in the night sky, while the meditative lyricism of Gabriela Peña-Kim’s violin was the holy vessel that transported you skyward.

That was followed by “Joy Boy,” written in 1974, four years before “Spiegel” and, like it, a mirror. Only this mirror is Eastman looking unflinchingly at himself. One of the first of his provocatively titled pieces (“Gay Guerilla” is another, as is “Evil ...,” the second half of that title being the N-word), it has as few harmonies as Pärt’s score and as much shimmer. But Eastman’s notation is so vague as to be almost meaningless. He implied that it was for a quartet of singers, or maybe of instrumentalists, or maybe both. The L.A. Phil went all out with four singers and eight strings.

Unlike “Spiegel,” though, there is no stopping “Joy Boy” from the excited raucous behavior it received. The singers whooped it up, howling to the night sky like wild animals. Those handful of chords implied multitudes as they were jiggered, pulled apart and put back together again.

Take your transcendental pick, the program seemed to say: Pärt’s purity or Eastman’s animistic urges. Pärt’s “Summa,” a spiritually unruffled short string quartet that followed, was, thus, either salvation or simply calm before the next Eastman irruption.

In fact, something more exceptional was afoot. Neither Pärt nor Eastman may be what he seems. However different their cultural backgrounds, both were trained as staunch formalists — Pärt in the old Soviet conservatory system and Eastman at Curtis and Cornell. Each created a persona. Photos of Pärt from his school days show the bearded mystic of now to have been then something of a jock. Eastman, on the other hand, early on revealed a dreamy, mystical side.

Moreover, what struck me when I first met each composer was a shared whimsical sense of humor. Each displayed a shyness that seemed not entirely sincere, as if it were a shield. I’ve consequently never entirely trusted the surface of either reclusive composer’s music.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

Rountree’s inspired performances of Pärt’s “Fratres” and Eastman’s “The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc,” two fabulous pieces for 10 cellos written four years apart (1977 and 1981) and played after intermission, uncovered, alternately, passion and spirituality. Rountree brought out the extremes of such otherness in both.

“Fratres” is all glassiness, and it too has been a moody choice for filmmakers, the sound of what can’t be said, be it a documentary about Auschwitz or a feature set in New York City. You may have caught it in “There Will Be Blood.” But for Rountree, every carefully ethereal gesture held something downright fleshy in its sound.

Meanwhile, Rountree, who is on a mission to make Eastman essential, brought out the sanctity of “Joan d’Arc,” one of Eastman’s last and greatest works, which also be will performed at the Proms in London next week. Cellos break from the rhythmic intensity with swooping, lyrical flights as though they represent the spirit leaving the body.

There are near-infinite conventional ways the L.A. Phil could have given its first chamber music concert in the Ford, now that the orchestra is running the venue at L.A. County’s behest. Instead, it offered an unexpected, revelatory program as a special gift to first responders and other invited guests in an idyllic setting, by far most meaningful live event I’ve attended since the pandemic.

A word about the state of the Ford. It remains lovely and friendly. Other than the piano in “Spiegel” being too loud, amplification proved involving. And I wish success to Todo Verde, the local, plant-based Latin American food service, as refreshing (and maybe challenging) an idea for the Ford as Pärt and Eastman.

The sad but important story of neglected minimalist Julius Eastman is reaching new audiences courtesy of Wild Up, L.A. Phil and N.Y. Phil.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.