There is perhaps no more satisfying sendoff to the xenophobia of the Trump era than an exhibition that rewrites American art history and, in the process, makes it more Mexican.

That exhibition is âVida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945,â which opened at New Yorkâs Whitney Museum in February and, one pandemic later, has miraculously managed to remain on view. The show takes some of the most recognizable U.S. painters of the first half of the 20th century and meticulously documents the ways in which those artists were indelibly shaped by the politics and aesthetics of the Mexican mural movement.

Jackson Pollock. Philip Guston. Jacob Lawrence. Thomas Hart Benton. Ben Shahn. Charles White. The list of artists influenced by the Mexicans reads like a literal whoâs who of American painting.

The three major Mexican muralists â Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and JosĂŠ Clemente Orozco (known collectively as los tres grandes) â all spent long stretches in the U.S. throughout the 1930s. During that time, they taught and exhibited and completed mural commissions in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit and New York.

Guston helped produce a mural by Siqueiros in L.A. for the Chouinard Art Institute; Shahn served as an assistant on Riveraâs infamous Rockefeller Center mural in New York (the one that was destroyed because Rivera included an image of Vladimir Lenin in the composition).

The presence of the Mexican muralists helped shift the course of American art, feeding an interest in socially, politically and racially conscious work that engaged the broadest possible viewing public.

Lawrence and White were inspired by Orozcoâs architectonic compositions and the visceral ways in which he portrayed struggle, elements that found their way into the American artistsâ depictions of the Black experience in the United States.

Shahn, the relentless chronicler of American labor, was influenced by Riveraâs densely packed scenes. Guston was motivated by the politics â and later went on to produce other socially minded murals (including one in Morelia, Mexico, with friend and colleague Reuben Kadish). Late in his career, Guston would become known for his darkly subversive canvases of the Ku Klux Klan (canvases that inspire controversy still).

The influence extended beyond the canvas. Los tres grandes indirectly helped shape U.S. cultural policy too.

In 1933, George Biddle, an artist who had spent time with Rivera in Mexico, wrote a letter to his friend Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had recently been sworn in as president. In it, he told Roosevelt about the ways in which the Mexican government had funded the creation of murals on government buildings as a way of expressing âthe social ideas of the Mexican Revolution.â

Roosevelt passed the letter along to the Treasury Department, which launched a public works project in government buildings. This was followed, a year later, by the establishment of the Works Progress Administrationâs Federal Art Project, a program that helped keep thousands of artists employed during the Great Depression, and resulted in the production of thousands of public murals and works of sculpture.

The historic links between prominent American artists and los tres grandes have been fairly well documented. (There is a rather legendary photo of Pollock hanging out with Siqueiros outside a workshop that the Mexican artist led in New York during the 1930s.) But âVida Americanaâ is the first exhibition to systematically explore the ways in which those linkages reshaped the Americans â and the way in which it reframes a well-trod history is seismic.

âThe idea that the French influenced U.S. art history, that still remains the case,â says Whitney curator Barbara Haskell, who conceived the exhibition. âBut this upends that.â

As Kadish once said: âSiqueiros coming to L.A. meant as much then as did the Surrealists coming to New York in the â40s.â

Even Pollock, the rugged, Wyoming-born icon of U.S. painting, saw the nature of his work shift as a result of his encounter with the muralists. The artist spent formative years in Los Angeles, during which he paid a visit to Orozcoâs mural of Prometheus at Pomona College, a work he described as âthe greatest painting done in modern times.â

After his move to New York, Pollock worked at Siqueirosâ Experimental Workshop in Manhattan, where he tried out different materials. (Siqueiros was an important innovator in that arena, early on employing industrial materials such as car paint and spray guns.)

The arrival of âVida Americanaâ amid a national election â one involving a sitting president who has long espoused anti-Mexican rhetoric â lands like a call for greater tolerance. It also forces some intense self examination, since to admire 20th century American painting is also to admire its Mexican influences.

Plus, the subject matter couldnât be more relevant.

âThese are themes that are still so active, whether itâs unemployment or racial injustice or the fight for workers rights,â says Haskell, who organized the show in collaboration with assistant curator Marcela Guerrero and curatorial assistants Sarah Humphreville and Alana Hernandez.

Another interesting parallel between today and that era: During the Great Depression, even as arts institutions were hailing the genius of the Mexican muralists, the U.S. federal government was busy ârepatriatingâ â a.k.a. deporting â Mexicans and Mexican Americans, characterizing them as âa great financial burdenâ to the country.

If you arenât in New York to see the show, the beautifully illustrated catalog, published by Yale University Press, offers great consolation.

Siqueiros coming to L.A. meant as much then as did the Surrealists coming to New York in the â40s.

— Reuben Kadish, painter

Interestingly, a good part of the âVida Americanaâ story takes place in California.

Rivera painted key murals in the Bay Area â at the San Francisco Art Institute and City College of San Francisco. Orozco painted at Pomona. Siqueiros taught mural painting at the Chouinard Art Institute and also painted the âAmerica Tropicalâ mural at Olvera Street in 1932, exploring themes of colonial genocide and depicting a dead Indigenous man under an American eagle. (The work famously was whitewashed, then restored in 2012.)

Figures such as Alfredo Ramos MartĂnez, a turn of the 20th century painter who was born in Mexico but made Los Angeles his home in the 1930s, also were an important part of the scene, depositing murals all over Southern California (including Scripps College). In addition, his work is held in the permanent collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Ramos MartĂnez has numerous works in the show, including a stunning canvas from 1940 titled âThe Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca),â which offers a cinematic close-up of a woman who impassively stares down the viewer.

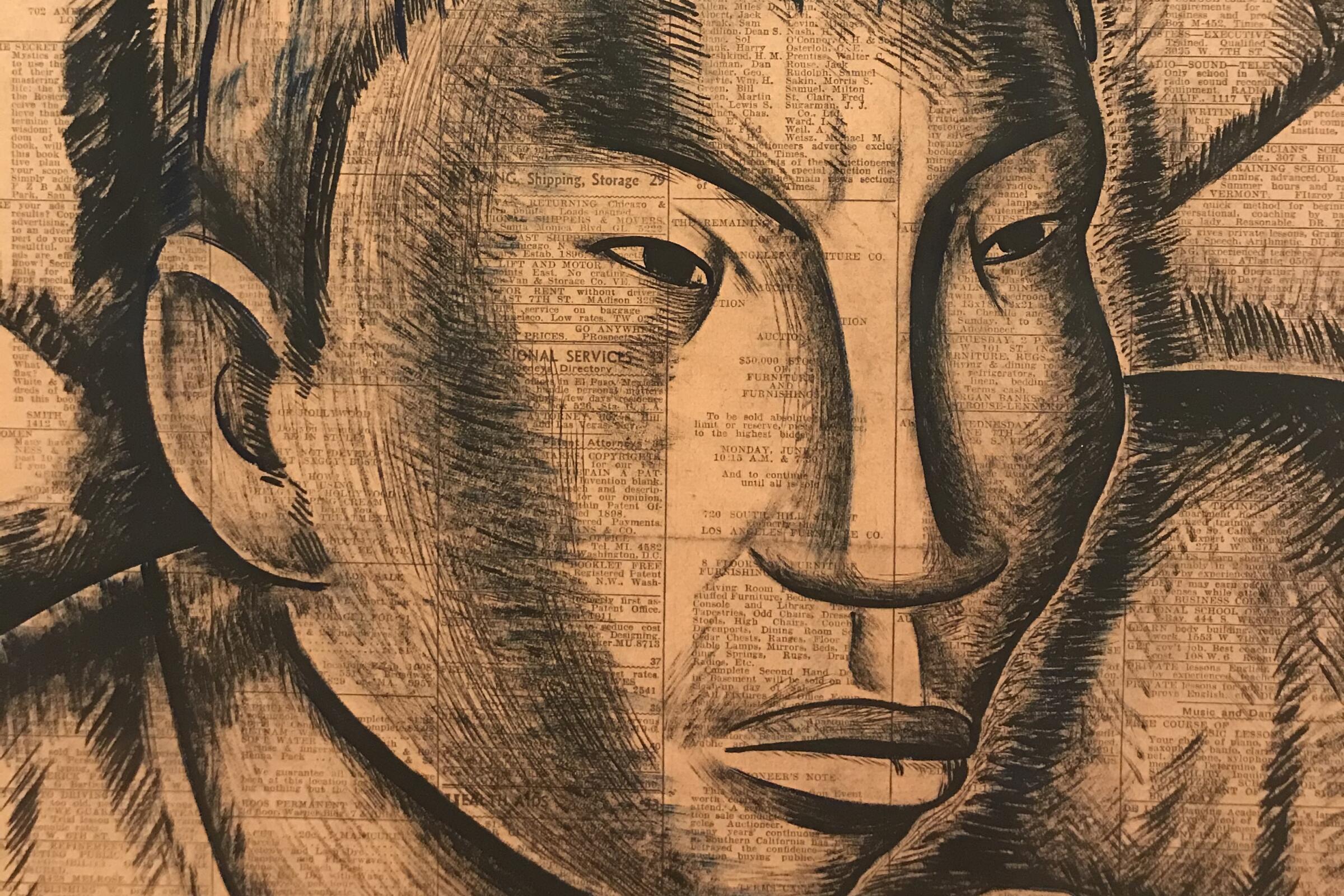

But most poignant is a drawing of a man on a sheet of Los Angeles Times newsprint. Amid the personals and ads for auction sales, the viewer is forced to confront the contours of the Indigenous manâs face. His story may not be written on the pages of the newspaper but it is there. You just have to look for it.

"Vida America: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945"

Where: Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort St., New York

When: Through Jan. 31

Info: whitney.org