Appreciation: How artist Peter Alexander caught clouds in a box and used color to profound effect

- Share via

In American art since the 1960s, has there been a more profound colorist than Peter Alexander?

The artist, who died Tuesday morning at his Santa Monica home at 81, regularly harnessed the pre-linguistic power of sensuous color to extraordinary ends.

He did it through a surprisingly wide variety of means. Alexander began with sculptures made from cast polyester resin, shifted to intense pastels on board, moved into paintings improbably composed on black velvet and, later, more conventionally on canvas. Drawings and prints kept the color-engine humming through it all.

So did the landscape of Southern California, where Alexander was born in 1939.

Artists, as much as rendering the visual features of a place, give form to acute intangibles. Landscape is to Alexander’s art what the rambunctious, newly modernized streets of Paris were to Camille Pissaro in the 19th century or China’s ancient granite mountains were to Dong Qichang 300 years before that. Pissaro evoked a unique urban energy and Dong encapsulated an intellectually rigorous history of thought.

Alexander grew up in comfortable Newport Beach as the nearby suburban metropolis at the western edge of America exploded in the decades after World War II. His art thrums with a quiet tension between poles of natural serenity and disorienting fabricated spectacle.

In a richly colored watercolor of a lone azure-blue cloud drifting through a fading crimson sky above the black silhouette of a hill sliding down toward the Pacific Ocean, the hypnotic beauty of pure nature is inseparable from the queasy, crafted splendor of popular culture. Luxurious seduction by sunset at the beach merges seamlessly with thumbing through a deadening rack of mass-produced greeting cards.

A surfer inspired by the properties of water and light, Alexander was one of the Light and Space artists who imbued minimalism with SoCal buoyancy.

Light is the key. Whatever his medium, the work Alexander made over 50 years articulates the distinctive, late-20th century intersection of natural and artificial light — an illumination at once physical and, as always, inflected with light’s cognitive and transcendent metaphors.

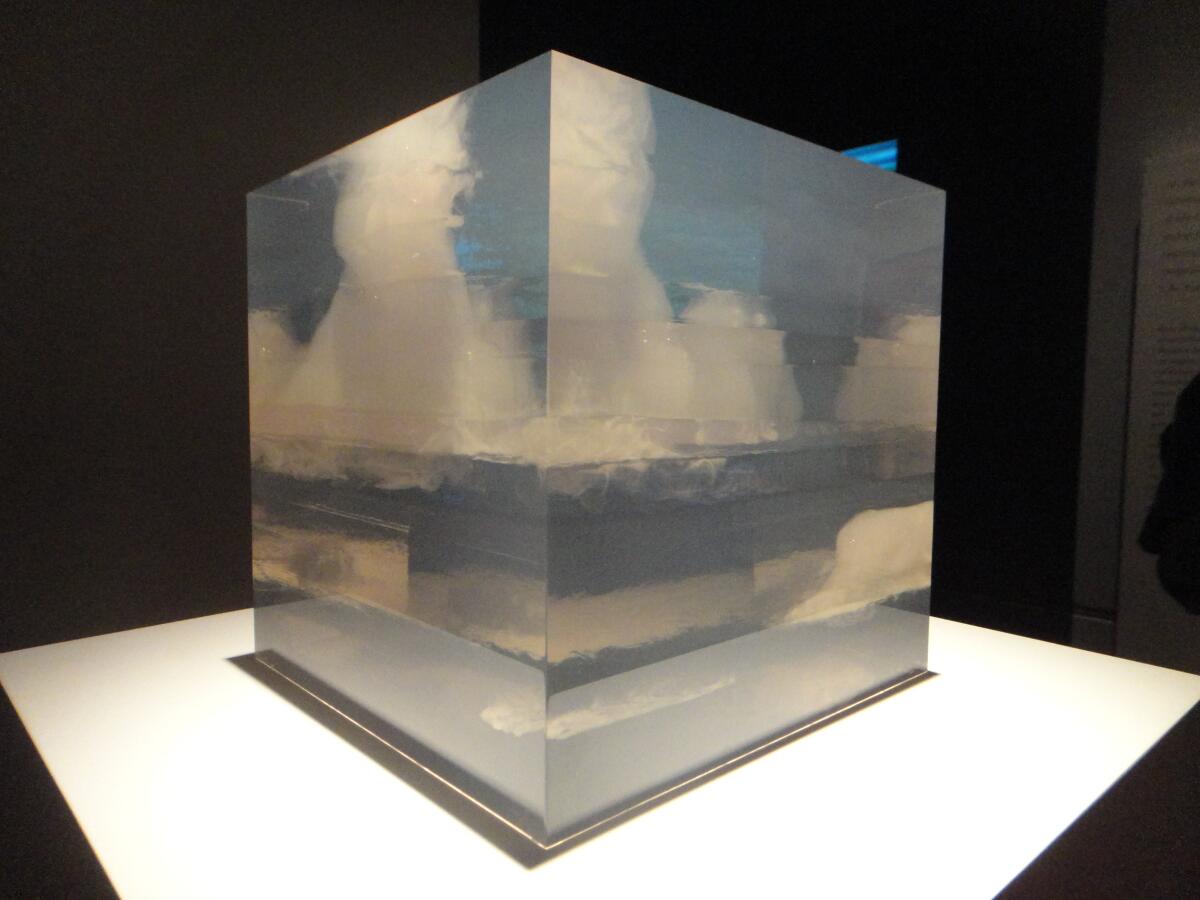

It began in 1966 with a cube of polyester resin, just 9 5/8 inches on a side. The otherwise unimposing cube encloses mysterious vapors made from an injection of watery mist into the not-yet-hardened plastic. A flaw in commercial fabrication becomes an inspiration in an artist’s studio.

Depending on ambient light and the angle of vision, color shifts between airy blue and a smoggy, yellowish-gray hue. “Cloud Box” is like a small, immobilized chunk of mid-1960s L.A. sky, cut out with a miraculous saw and deposited onto a pedestal for close examination. (The city’s dirty air was a poster child for congressional passage of the Clean Air Act in 1963.) The boxed and billowy clouds, no matter how physically small and intimate, seem very far away, like the swelling puffs across the sky in a Jacob van Ruisdael landscape of the Haarlem bleaching fields, where Dutch linen was once produced.

Many of Alexander’s Minimalist resin sculptures take the form of tall, slender wedges and pyramids. Color is transparent and nearly clear at the top, sliding incrementally to dense and almost opaque at the base. If “Cloud Box” encompasses sky, these wedges frame the ocean, embodying the way light passes through its glimmering surface to its solemn depths.

Others are slender, 8-foot rods in triangular cross-sections, which lean upright against the wall, the object’s rough or polished surfaces creating prismatic effects. Or else milky cylinders split in two and lined up across the wall, their repeating forms optically blurred.

Alexander had initially set out to be an architect — he studied design at schools in Philadelphia, London and Berkeley and worked at home in the offices of Richard Neutra and William Pereira — and gestures toward engagement with the built environment are frequent. Like much American painting and sculpture of the late 1960s, the work on which his reputation developed was non-figurative, geometrically precise, perceptually oriented and architecturally related.

Color, though, was central. Color was a contested territory in the day’s critical arguments, celebrated for its seductions in attention-grabbing exhibitions like 1964’s “Post Painterly Abstraction” at the old Los Angeles County Art Museum in Exposition Park but soon looked upon with skepticism (for the same reasons of its sensuality) in the sober rise of Conceptual art.

The artist quit using polyester resin in 1972 because it was a health hazard. (Around 2000 he began using a safer acrylic.) What Alexander did next seemed surprising. He chucked abstraction, exalted by Modernists as the highest of High Art, and started painting sunsets.

What could be more vulgar? For art, probably nothing — except perhaps for discount paintings on gift-shop black velvet, so he started painting sunsets on that.

With glitter, for good measure.

A decade later, Julian Schnabel would get ink in New York for operatic, ostensibly disruptive velvet paintings. In a way, Alexander’s much earlier move to the medium wasn’t so startling. For one thing, Alexander didn’t have an inelegant bone in his body, and neither does his art.

For another, pop culture, which the sunset works embraced with fervor, had been integral to the very idea of sculpture made from plastic, rather than stone, wood or metal. The paintings’ images now picture the light, both natural and artificial, that had made the abstract sculptures so compelling.

The first paintings are almost Art Deco in style, featuring a low horizon line above a narrow strip of jet-black velvet, topped by an explosive zigzag pattern of light dotted with meteor-shower bursts. Later ones loosen up. A range of emotional vectors can be inferred, from turbulent and roiled to monkish and unruffled.

Notably, the sun is never seen. Only illuminated atmosphere is — the very stuff of Light and Space.

Alexander was instrumental in establishing Light and Space as the city’s first original contribution to world art, together with peers who include Robert Irwin, Doug Wheeler and Larry Bell, as well as such predecessors as John McLaughlin, Karl Benjamin and June Harwood.

In the 1980s, the underwater allusions of the late 1960s color wedges came roaring to the foreground. Spectacular paintings on unstretched black velvet are collaged with bits of gauzy fabric, thick squiggles of glue studded with rhinestones, pearlescent buttons and dangling sequin strips. The deep is shallow, the shallows deep.

The most famous of these was a 40-foot mural for Rebecca’s, a popular nouvelle Mexican restaurant in Venice Beach. Designed by Alexander’s friend Frank Gehry, the interior was adorned with the architect’s sculptural lamps of fish, crocodiles and an enormous, red-crystal octopus chandelier. Alexander’s mural provided its snazzy coral reef.

Sunsets and the sea were archetypes of an Emersonian blend of reason and faith for such great 19th century American landscape painters as Thomas Cole and John Frederick Kensett. But their power had long since been ground down into stereotypes by mass forces like Kodak and Hallmark. One by one, Alexander took them back, honoring their distinctly modern beauty.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.