Commentary: Glenn Gould’s decades-old radio documentaries still resonate. Podcasters, take note

- Share via

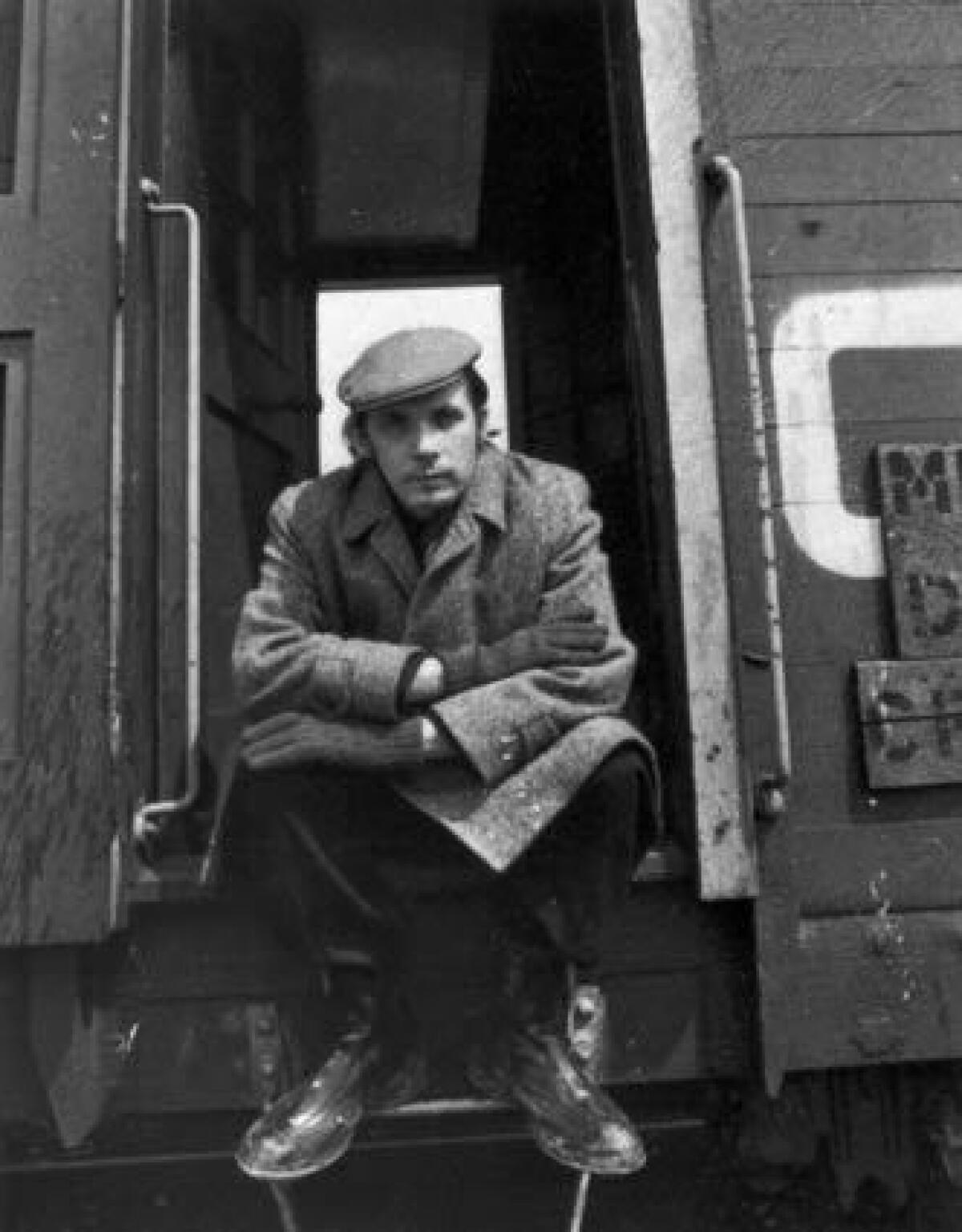

Glenn Gould gave his last public concert at the Wilshire Ebell Theater in L.A. 56 years ago. He was 32. Two years later, he predicted in a magazine article that “the public concert as we know it today will no longer exist a century hence, that its functions would have been entirely taken over by electronic media.”

The famed Canadian pianist was beginning to experiment with radio as a musical form. In 1967, he produced the first of what would become, with seemingly astonishing prescience for our pandemic predicament, the “Solitude Trilogy.”

Now with the performing arts closed down by the coronavirus, could Gould have been more than half a century ahead of his time?

One the greatest and most original and shockingly unconventional musicians of the 20th century, Gould went even further in his antipathy to live performance. He called it downright immoral. For him, the immediacy of art could best be achieved through the artist’s significant social distancing from the public. Technology was the most efficient delivery system.

Given that the episodes of the “Solitude Trilogy,” which Gould produced between 1967 and 1977, are already among the finest radio of all time, we have more than enough reason to revisit them. Gould’s gripping radio documentaries, moreover, make essential listening for an era of creative podcasts in which the medium offers new interest in how radio pioneered experiments with narrative.

An isolationist at heart who had always been more at home in the recording studio than in the concert hall, Gould often sought refuge outside his native Toronto. In “The Idea of North,” the first episode of the “Solitude Trilogy,” he traveled to the farthest reaches of north Manitoba that Canadian rail would take him and where “all who spend time there are changed by the experience.”

Gould then turned to villagers on Newfoundland island for “The Latecomers” to explore the illumination of isolation along with its attendant ills. With “The Quiet Land,” he sonically sewed together the existential struggles within Manitoba’s rural Mennonite communities to remain in the world but not of the world as modern urban life threatens.

Between Gould and Marshall McLuhan at the University of Toronto, the city had become a magnet for new-media thinking in the 1960s, abetted by the open-minded and well financed Canadian Broadcasting System, or CBC. At precisely the time Gould stopped performing, McLuhan published his influential “Understanding Media,” in which he characterized radio as a hot medium, capable of vividly taking over the listener’s imagination.

It was surely no coincidence that just a couple of weeks after Gould stopped concertizing, he had lunch with McLuhan, who admired the pianist enormously and went on to encourage his radio projects and assure him that all sound sources are music at heart. “Bless Glenn Gould for throwing the concert audience to the junkyard,” a delighted McLuhan later wrote.

Gould approached “The Idea of the North” as though a musical score. Voices of a surveyor, a geologist, a nurse, a government official and a writer intertwined as though contrapuntal voices in a Bach fugue or suite. Several could be sometimes be heard at once, each artfully edited, syllable by syllable, so that their rhythms made a certain sense as one emerged and another faded.

Wally Maclean, the surveyor whom Gould characterized as “at once a pragmatic idealist, a disillusioned enthusiast,” serves as a guide to the travails of limitless expectation in limitless space. But when the other voices of northern experience in all its wonder and wrenching disenchantment intrude, you hear both sides expressed at once. You may chose which to follow, but you can never completely filter others out. Without becoming aware of it, you find concentration is the art of rapt intent.

And what lines! Maclean quotes Pascal in having said that most of humanity’s troubles would be done away with if we would stay in our room. There is another’s observation of feeling cooped up in wild open spaces because of the danger of getting lost.

Sound effects for Gould are not just atmospheric but also compositional. Radio technology developed rapidly during the decade of making the trilogy, as did Gould’s studio skills. “The Idea of North” is mono, although Gould does a marvelous job in creating the illusion of space in the way he manipulates sound. With “The Latecomers,” he had the advantage of stereo, allowing for greater contrapuntal complexity for the voices.

Newfoundland, Gould found, is a place of idealism but not always satisfaction. Solitude is said to be the source of real knowledge. In villages with no locks on doors, no crime, no police, there is no need for government. Isolation fosters creativity, one resident tell us, because an “artist who’s worth anything works best alone.”

But the ever-presence of isolation, which Gould represented by a continual backdrop of breaking waves, inhibits creativity, all energy going into survival. Having to deal with the harsh reality of the surroundings, it is “hard for students to come to grips with abstract thought,” one resident says, making isolation “fifty percent good, fifty percent bad.”

Peter Sellars — opera director, spiritual thinker, optimist — reflects on changes triggered by coronavirus. Amid tragedy, what new life might come forth?

The issues become ever more disquieting in “The Quiet Land,” just as the radiography at the CBC becomes ever more advanced. A you-are-there soundscape of bells, traffic, children playing and church congregations is here, the aural representation of isolation in the midst of abundance for the small Mennonite community in Manitoba wanting to preserve a life led with simplicity and Christian purity.

Goodness is of essence. A woman begins her day with a prayer before going to work: “God help me this day to be kind to people who annoy me most.”

Annoying questions, however, abound. Can a Mennonite composer insert 12-tone compositions into the music of a people who don’t understand it? Can a common base continue in the modern world?

The voices are diverse. The word of the church is ever stalwart. Meanwhile the world goes about its business. The good, the indifferent and the demanding do not produce a cacophony. Gould filters voices so they have less or more presence, whether to heighten or diminish emotion, or simply to reveal surroundings teeming with life no matter how intense the solitude.

The pianist made other documentaries for the CBC around musical personalities he particularly admired: Stokowski, Schoenberg, Casals and, believe it or not, Petula Clark. Each is, in its own idiosyncratic way, an irresistible evocation of a person, an ethos and a type of music, and all can be found from various sources here and there.

The CBC has released the “Solitude Trilogy” and the Stokowski and Casals programs on CD. That, or the better streaming services, is how they are best heard to get the full advantage of Gould’s use of sound. YouTube is the main source for the others.

In “The Quiet Land,” a Mennonite theater buff describes Beckett’s play “Waiting for Godot” as “waiting for God to come into their lives and give them meaning.” At least we don’t have to wait for Gould, who has never stopped haunting us since his death in 1982, to give us meaning as we wait, despite the pianist’s predictions, for concert life to return.

The last thing we need is another Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony — unless Teodor Currentzis is conducting. His new recording brings much-needed catharsis.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.