John Baldessari, in his own words: How an immigrant father shaped the artistâs voice

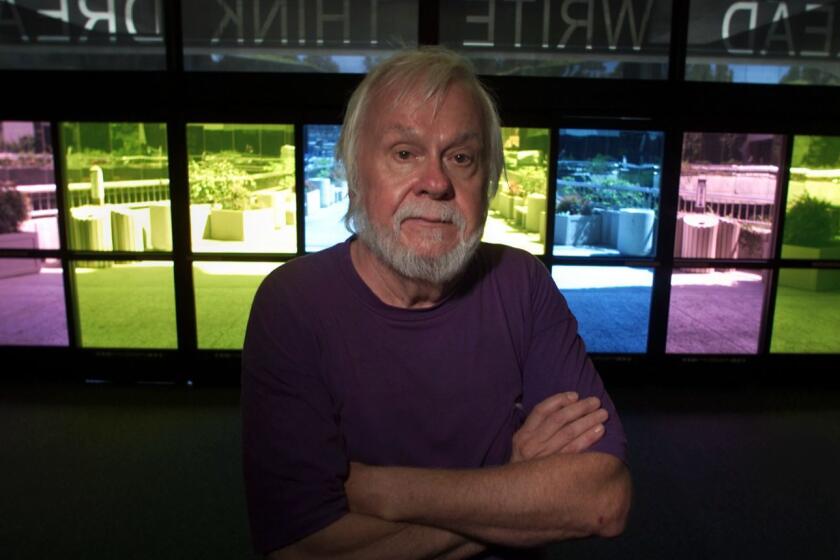

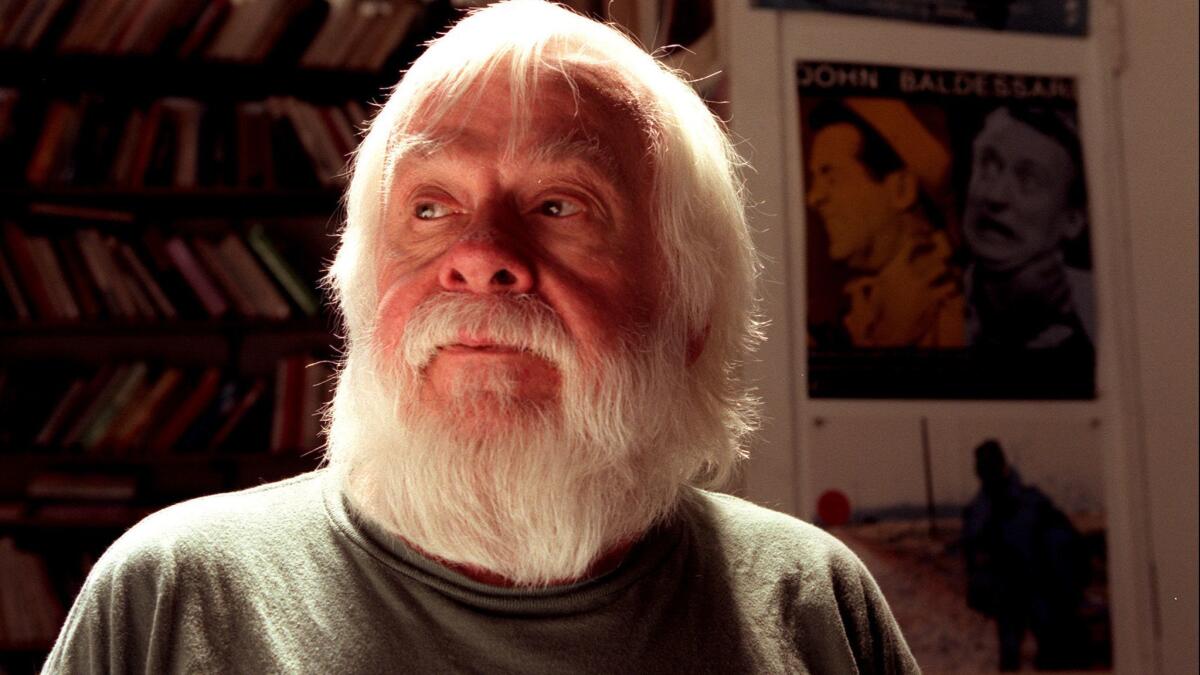

When legendary Conceptual artist and teacher John Baldessari died Thursday at 88, he left behind not only a legacy of work and ideas but also generations of successful artists whom he taught to see and to create in new ways.

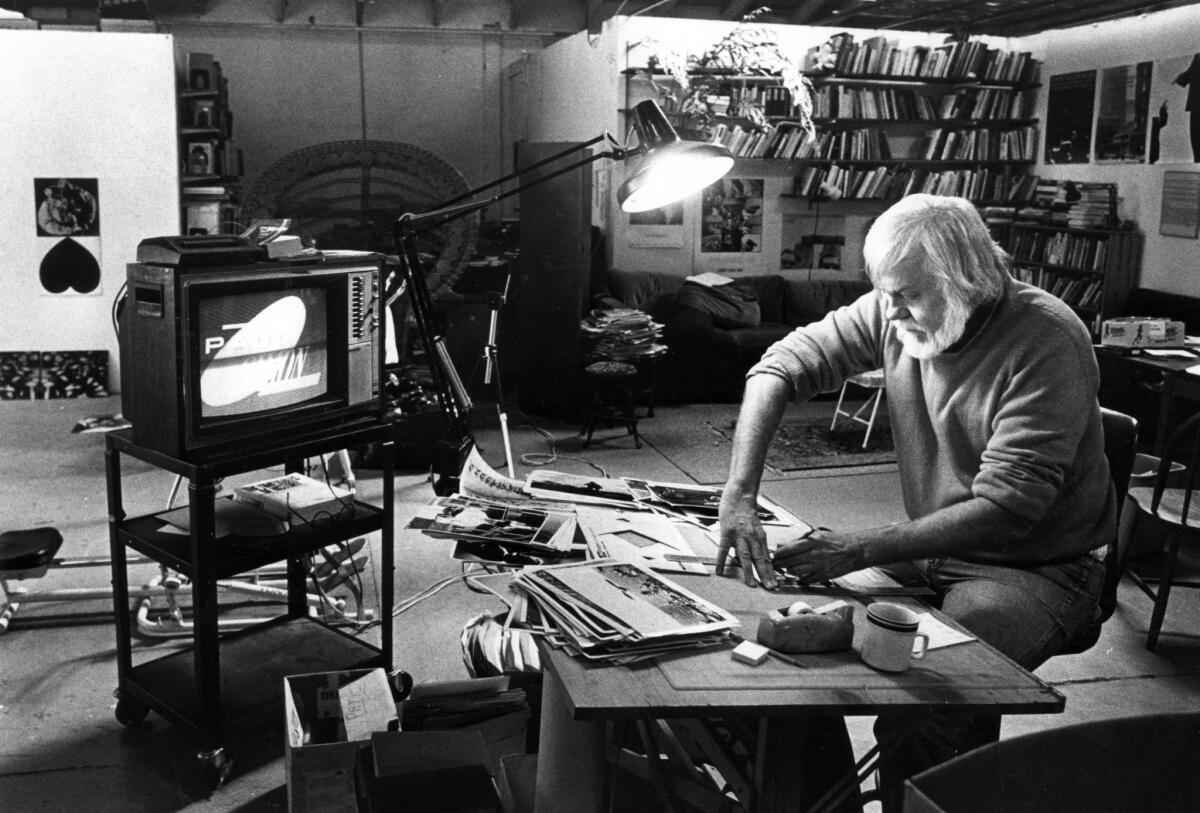

Baldessari was an early part of innovative art departments at UC San Diego, California Institute of the Arts in Valencia and UCLA. I met him over the years and recall vividly a visit in 1986 to his barn of a studio at the time, a place in Santa Monica so overflowing with stacks of books, magazines and other raw material you never knew where to put your feet, much less your coffee cup.

He was a great conversationalist, replete with wit and wisdom, and in December 1998, we spoke at length of his passion for both teaching and California for my oral history, âState of the Arts: California Artists Talk About Their Work,â published in 2000 by William Morrow.

Hereâs part of what the dean of West Coast Conceptualism had to say, in his own words, edited for length and clarity:

My father had a salvage business tearing down houses and, with those materials, building other houses. He wasted nothing and recycled everything. He had bins for steel, iron, brass, copper. I had to take nails out of lumber and straighten the nails and take apart faucets to clean and paint them, so I have this feeling for things like that.

He was an Austrian citizen, from the Southern Tyrol, and he died at 90 still speaking broken English. But I became very aware of communication. I was trying to make myself clear to my father, talking in as clear sentences as possible and saying things in an understandable way.

As I began to teach, I could see the same need. I already had been primed for it. And as I continued with teaching and art, I began to see how they both shared the same problem of communication. I saw how you could obfuscate, be crystal clear or do anything in-between. You could play your audience like a musical instrument.

After I graduated from San Diego State, I felt I couldnât just go out in the world and call myself an artist, because I didnât know what an artist was. I began teaching high school and junior high school until at a certain point, I wanted to have more time to paint.

I got a call to teach at a California Youth Authority camp in the mountains outside San Diego. It was an honor camp, no walls. One of the kids there asked me to open up the arts-and-crafts room at night so they could work. I made a deal with them: If they would cool it in class and pay attention, I would open up the classrooms at night. It worked like a charm.

I had an epiphany when I saw that these kids cared more about art than I did at the time. My idea of art then was just some sort of masturbatory activity that didnât help anybody out in the world at all. I had this sort of social conscience, I suppose, and I thought, here are these kids who really value art for some reason. So I figured my gifts are in art and Iâll just work in art, maybe somewhere along the line Iâll figure it all out. I canât say that I have, but at least it did kick-start me.

In the late â60s, it became clear that somehow I was on the wrong track defining art as painting and painting as art, and that what I was doing wasnât painting.

I was doing text and photo paintings and paintings solely with text. I had ignored photography for a long time, thinking it was a high school infatuation, but now I had this idea that I would do visual note-taking. I would go out with my camera and take photographs of things that might be information for my paintings. Then I got another epiphany. I asked myself: Why do I have to translate all of this information into painting? Why canât it be art in itself?

Now itâs not such an interesting idea but that was a little bit heretical, I suppose, at the time. I remember taking these canvases with text and photos around to Los Angeles galleries and just getting blank stares.

I was exploring all kinds of ways to appropriate images from other sources, shooting things randomly off the TV or with an automatic timer. Having a camera outside my studio. Anything where my own selection process wouldnât come into play. I began to shoot things out of magazines and books, imagery that wasnât meant to be art. I was probably trying to figure out why some things are art and other things are not.

Living in California, as opposed to New York or Europe, affords a certain kind of freedom, because we donât have the weight of history in Los Angeles. If Iâm sitting in a cafe in Vienna, say, people are going to tell me that Mozart used to sit where Iâm sitting. If Iâm in New York, there are galleries, museums and publications around constantly to remind you that art is a major industry there. I think it was an advantage living here in that I got away from this pressure of history.

Do I think Los Angeles has any influence on my work? I always answer that by saying that a shark is the last one to criticize saltwater. If youâre immersed in something, you canât see it.

It dawned on me that I had to live someplace that I thought was ugly, and Los Angeles was my choice, probably because it replicated National City. If things are too beautiful, why would you want to create anything beautiful? If things are too idyllic in my environment, I go somehow crazy. I could not live in Beverly Hills or Bel Air.

My studio is a mess. I trip over things, and itâs full of books, records and magazines. I know where everything is, but Iâm a pack rat. I think Iâve replicated my fatherâs salvage store. He couldnât throw anything away because he saw value in everything. I see visual value in everything.

Arguably the most influential Conceptual artist of his era, Baldessari also shaped a generation of talent while teaching at UCLA and ArtCenter.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.