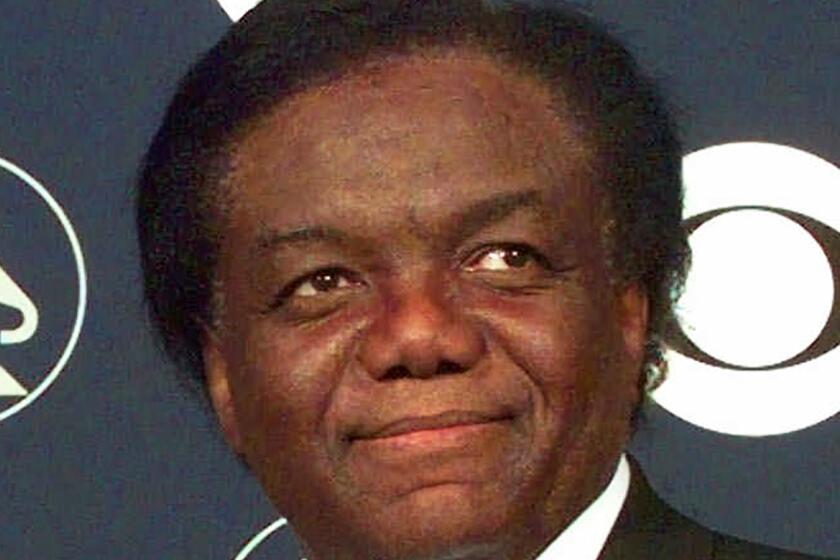

Motown’s Barrett Strong, known for ‘Money’ and ‘I Heard It Through the Grapevine,’ dies at 81

NEW YORK — Barrett Strong, one of Motown’s founding artists and most gifted songwriters, who sang lead on the company’s breakthrough single, “Money (That’s What I Want),” and later collaborated with Norman Whitfield on such classics as “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” “War” and “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone,” has died. He was 81.

His death was announced Sunday on social media by the Motown Museum, which did not immediately provide further details.

“Barrett was not only a great singer and piano player, but he, along with his writing partner Norman Whitfield, created an incredible body of work,” Motown founder Berry Gordy said in a statement.

Strong had yet to turn 20 when he agreed to let his friend Gordy, in the early days of building a recording empire in Detroit, manage him and release his music. Within a year, he was a part of history as the piano player and vocalist for “Money,” a million-seller released early in 1960 and Motown’s first major hit.

Strong never again approached the success of “Money” on his own, and decades later fought for acknowledgment that he helped write it. But with Whitfield, he formed a productive and eclectic songwriting team.

While Gordy’s “Sound of Young America” was criticized for being too slick and repetitive, the Whitfield-Strong team turned out hard-hitting and topical works, along with such timeless ballads as “I Wish It Would Rain” and “Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me).” With “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” they provided an up-tempo, call-and-response hit for Gladys Knight and the Pips and a dark, hypnotic ballad for Marvin Gaye, his 1968 version becoming one of Motown’s all-time sellers.

In four years, Dozier and brothers Brian and Eddie Holland crafted dozens of top 10 songs and mastered the blend of pop and rhythm and blues.

As Motown became more politically conscious late in the decade, Whitfield-Strong turned out “Cloud Nine” and “Psychedelic Shack” for the Temptations and for Edwin Starr the protest anthem “War” and its widely quoted refrain, “War! What is it good for? Absolutely ... nothing!”

“With ‘War,’ I had a cousin who was a paratrooper that got hurt pretty bad in Vietnam,” Strong told L.A. Weekly in 1999. “I also knew a guy who used to sing with [Motown songwriter] Lamont Dozier that got hit by shrapnel and was crippled for life. You talk about these things with your families when you’re sitting at home, and it inspires you to say something about it.”

Whitfield-Strong’s other hits, mostly for the Temptations, included “I Can’t Get Next to You,” “That’s the Way Love Is” and the Grammy-winning chart-topper “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” (sometimes rendered as “Papa Was a Rolling Stone”). Artists covering their songs included the Rolling Stones (“Just My Imagination”), Aretha Franklin (“I Wish It Would Rain”), Bruce Springsteen (“War”) and Al Green (“I Can’t Get Next to You”).

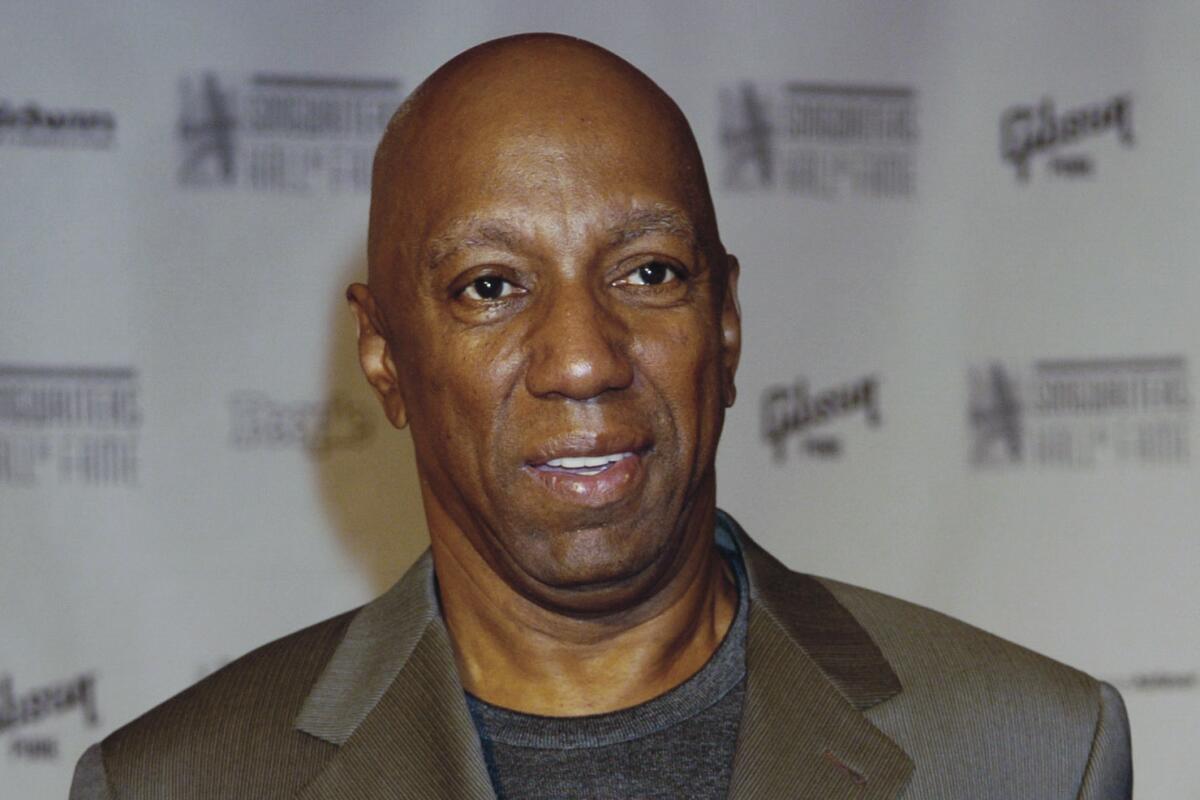

Strong spent part of the 1960s recording for other labels, left Motown again in the early 1970s and made a handful of solo albums, including “Stronghold” and “Love Is You.” In 2004, he was voted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, which cited him as “a pivotal figure in Motown’s formative years.”

Motown legend Berry Gordy said he had “come full circle” at a 60th anniversary event for Motown Records on Sunday.

Whitfield died in 2008.

The music of Strong and other Motown writers was later featured in the Broadway hit “Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations.”

Strong was born in West Point, Miss., and moved to Detroit a few years later. He was a self-taught musician who learned piano without needing lessons and, with his sisters, formed a local gospel group, the Strong Singers. In his teens, he got to know such artists as Franklin, Smokey Robinson and Gordy, who was impressed with his writing and piano playing.

“Money,” with its opening shout, “The best things in life are free / But you can give them to the birds and bees,” would, ironically, lead to a fight over money.

Get our daily Entertainment newsletter

Get the day's top stories on Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Strong was initially listed among the writers, and he often spoke of coming up with the pounding piano riff while jamming on Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say” in the studio. But only decades later would he learn that Motown had since removed his name from the credits, costing him royalties for a popular standard covered by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and many others and a keepsake on John Lennon’s home jukebox.

Strong’s legal argument was weakened because he had taken so long to ask for his name to be reinstated. (Gordy is one of the song’s credited writers, and his lawyers contended that Strong’s name appeared only because of a clerical error).

“Songs outlive people,” Strong told the New York Times in 2013. “The real reason Motown worked was the publishing. The records were just a vehicle to get the songs out there to the public.

“The real money is in the publishing, and if you have publishing, then hang on to it. That’s what it’s all about. If you give it away, you’re giving away your life, your legacy. Once you’re gone, those songs will still be playing.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.