Review: âPassages,â a beautifully acted romantic triangle, has major Sachs appeal

When you first meet Tomas (Franz Rogowski), the impulsive, insatiable and utterly impossible filmmaker who propels nearly every scene of âPassages,â heâs darting around the set of his latest picture and berating his cast and crew. Why, he fumes, are the extras sitting around like idiots with their empty drink glasses? Why canât an actor just walk down a staircase, without swinging his arms so awkwardly? Tellingly, this is the only time you really see Tomas at work, but his personal and professional misbehaviors turn out to be very much of a piece. On or off the set, heâs a callous control freak and a raging narcissist, someone who wants what he wants and doesnât care who he hurts in order to get it.

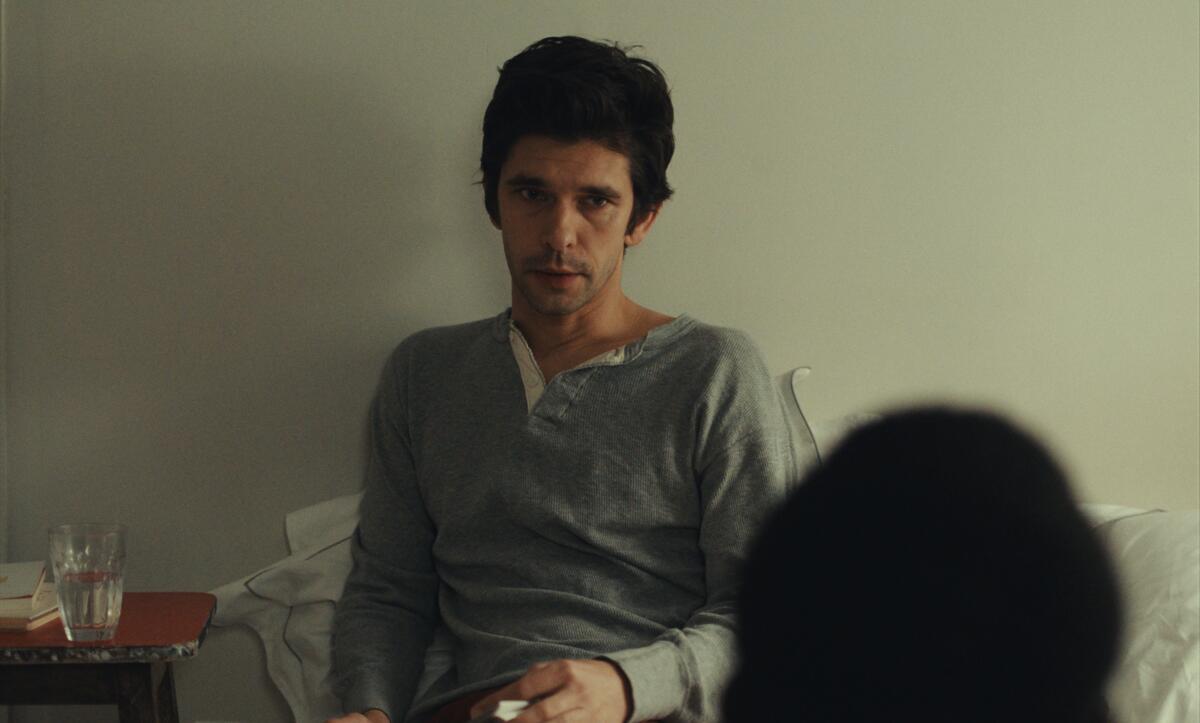

Chief among the wounded are his husband, Martin (Ben Whishaw), a sensitive soul whoâs learned to take Tomasâ every reckless, thoughtless deed quietly in stride. Martin is thus more exasperated than devastated when Tomas announces one morning that heâs just slept with Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos), a young woman he met at a party the night before. Whether this violates any parameters of their marriage is left unstated in a present-tense story thatâs refreshingly uninterested in overexplaining itself, its characters and their backstories. In time, though, Tomas doesnât just cross a line but obliterates it, moving in with Agathe and saying adieu to Martin for good â or so he thinks.

A torrid and thrillingly messy whirlwind of a movie, âPassagesâ was directed and co-written by Ira Sachs, a filmmaker with a gift for putting long-term relationships, gay (âKeep the Lights On,â âLove Is Strangeâ) and straight (âMarried Lifeâ), under the microscope. With âPassages,â a bisexual triangle set primarily in Paris, he has shaken up both the geography and the geometry, to pleasurable if disorienting effect. Those who admire the granular textures and socioeconomic nuances of Sachsâ New York stories (including his lovely Brooklyn-set drama âLittle Menâ) may well detect some easy cultural pigeonholing at work here, as if all it took were a French setting â or, more bluntly, a general air of Eurotrashy vice â to push a marriage in the direction of a mĂŠnage Ă trois.

To some degree, that bluntness is also borne out by the casting, even if the performances themselves are exquisite. For Exarchopoulos, best known for her star-making role in âBlue Is the Warmest Color,â Agathe is another (if rather less vivid) opportunity for her to play a naive, not-fully-formed Frenchwoman whose desires can overpower her better judgment. (Agathe, like the older version of âBlueâsâ Adèle, is an elementary schoolteacher.) And as Martin, Whishaw is as Britishly brittle-yet-vulnerable as only he can be, the stoic, sad-eyed cuckold trying to rise above and move on from the fray.

As for Tomas, a marvel of swaggering loucheness in his mesh shirts and dragon-embroidered crop tops, he is triumphantly liberated from any culturally specific expectations whatsoever. In dreaming up this character, Sachs and his co-writer, Mauricio Zacharias, may be tipping their hat to Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the sexually and cinematically prolific German filmmaker whose personal entanglements were as notoriously fraught and unruly as his movies. But even with that connection â and even within Rogowskiâs impressive gallery of ardent-lover protagonists (âGreat Freedom,â âTransitâ) â Tomas is an inimitably singular creature. Loathsome and magnetic, infuriating and unforgettable, he is, by several bed lengths, the most dynamic protagonist Sachs has given us, a vessel of pure, untrammeled id.

The dramatic structure of âPassagesâ is fairly straightforward: Tomas acts, and everyone else reacts. He seems to throw not just everyone around him but the movie itself off-balance. The story, as though racing to keep pace, often leaves some of its key developments shrewdly off-screen; the craftily intuitive editing (by Sophie Reine) allows weeks to pass and relationships to shift within the space of a single cut. Time moves swiftly in âPassagesâ and so does Tomas, racing between home and office, from social engagements to late-night trysts. A signature image is of Tomas racing through Paris on his bike; seeing the abandon in his eyes and the tension in his frame, you fear for his safety, and for the safety of anyone who crosses his path.

Even after he walks out on Martin, Tomas is forever barging in on him unannounced (and even shows up at the studio where Martin works as a graphic artist), selfishly reasserting his hold over a former partner whoâs trying in vain to get on with his life. When Martin begins seeing a hot-shot writer (Erwan Kepoa FalĂŠ), Tomasâ ensuing jealousy and regret â not to be confused with remorse â lead him to cruelly neglect Agathe, even after she tells him sheâs pregnant. He canât even bother to make a good impression on Agatheâs more traditional-minded parents (Caroline Chaniolleau, Olivier Rabourdin), who are thoroughly appalled by their daughterâs choice of partner.

The French actor finds the criticisms of breakout âBlue Is the Warmest Colorâ âstupid.â It didnât stop her from signing onto another complex, combustible romance.

You canât really blame them, although Sachs, surveying his characters with a remarkable equanimity, does his best to suspend easy judgment. He and his gifted cinematographer, JosĂŠe Deshaies, frame most of their dialogue scenes in long takes and medium shots, adopting an egalitarian perspective that lets you see how these characters interact with each other and with the very rooms they inhabit. You spend a lot of time early on in Martin and Tomasâ apartment, whose warm, inviting kitchen and stylish fixtures and furnishings testify to a life happily shared, at least some of the time. You also see how this apartment changes over the course of the story after Martin leaves, transforming from a once-cherished home into a zone of rage, resentment and misunderstanding.

And also of desire â persistent, inconvenient and finally undeniable. The most-discussed sequence in âPassagesâ is a Martin-Tomas sex scene, roughly two minutes in length, thatâs shot with remarkable candor and a cumulative, convulsive intensity. (This scene and presumably others like it led the notoriously sex-punitive Motion Picture Assn. to give the movie an NC-17 rating; the filmâs distributor, Mubi, rejected this outcome and opted to release it in theaters unrated.) Rather than fading tastefully to black, the movie lingers on a spectacle less remarkable for its spread legs and clasped buttocks than for its palpable collision of feelings: lust, anger, tenderness, confusion, bitterness, frustration, release.

Sachs doesnât give the sex any particular narrative emphasis; his matter-of-fact point is that this moment, and others like it, are as rich in dramatic significance and emotional complication as any of his charactersâ experiences, and should be approached with the same frankness and curiosity. And if he acknowledges the undeniable, fiercely disruptive power of sex, he is also more than aware of its limitations. The final passages of âPassagesâ feel at once sad and inevitable, suffused with a wisdom that, for Martin and Agathe, feels both hard-edged and hard-won. You suspect that Tomas may be in for a similar awakening, if he could ever bring himself to slow down.

'Passages'

Unrated

In English and French, with English subtitles

Running time: 1 hour, 31 minutes

Playing: Starts Aug. 4 at Landmarkâs Nuart Theatre, West Los Angeles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.