Review: âInu-ohâ is a psychedelic Japanese anime rock opera for the ages

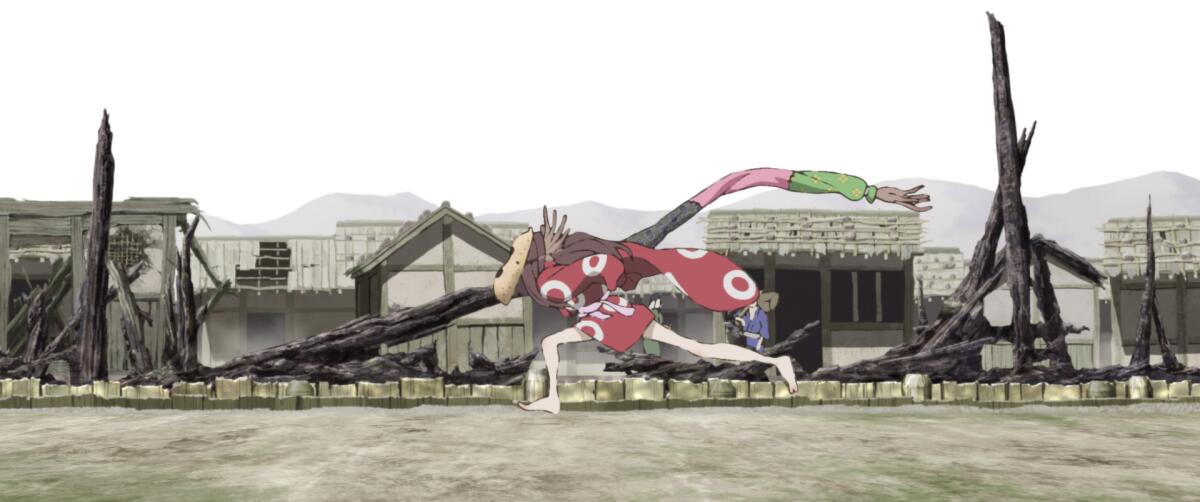

The phantom that haunts the eccentric Japanese rock opera âInu-ohâ is not the comeliest of creatures â not at first, anyway. Like most of the hallucinatory sights and transporting sounds in this feature-length anime, Inu-oh, as he comes to be known, tends to shapeshift in accordance with director Masaaki Yuasaâs whims. An ancient Noh dancer born under highly mysterious circumstances, he bursts into the frame on spindly human legs, an overgrown extendable arm flailing behind him like a kite. Two oddly positioned eyes peer out from behind a gourd-shaped mask that hides a face so terrifying, itâs a wonder it doesnât turn unfortunate onlookers to stone.

Inu-oh, inspired by a real-life performer of the same name (and voiced by Avu-chan, lead singer and songwriter for the band Queen Bee), here takes the misshapen form of a classic anime grotesque. But he also serves as something of a lesson to those he scares off, reminding them that peculiarity is not inherent cause for suspicion or fear. âInu-ohâ offers its own welcome demonstration of this principle. A rich, unstable alloy of history, legend, musical pageantry and cinematic psychedelia, it mounts an argument for mind-expanding, complacency-rattling art in a world that often prefers the opposite.

For your safety

The Times is committed to reviewing theatrical film releases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because moviegoing carries risks during this time, we remind readers to follow health and safety guidelines as outlined by the CDC and local health officials.

If that world sounds an awful lot like ours, it is also the politically divided 14th-century Japan against which âInu-ohâ unfolds. One of the concerns of Yuasaâs movie is how conflict and tragedy are enshrined in folklore, and the specific role that artists play in recording, distorting, overlooking and sometimes rescuing history. Even as a war rages between the nationâs northern and southern imperial courts, whispered memories persist of the Heike samurai clan, wiped out by their enemies, the Genji, in a furious battle at sea roughly 200 years earlier. (Their conflict was immortalized in the 12th-century epic âThe Tale of the Heikeâ; the movie was adapted by Akiko Nogi from Hideo Furukawaâs more recently published novel, âTales of the Heike: The Inu-Oh Chapters.â)

While the sunken Heike ships are regularly plundered by gold seekers, their real buried treasure, the movie insists, lies in their wealth of untold, soon-to-be-forgotten stories. The challenge of discovering and retelling those stories falls to Tomona (Mirai Moriyama), a traveling biwa player who grew up near that watery battleground, and Inu-oh, the unsightly outcast with whom he crosses paths. Years earlier, Tomona was blinded during a childhood accident, a tragedy that soon reveals itself as destiny. Unable to see â or be frightened by â Inu-ohâs visage, Tomona joins forces with this strange dancing demon. Together they forge an improbable musical alliance that will usher them onto the nationâs most popular outdoor stages.

In the context of a relatively staid and strictly government-regimented musical tradition, Inu-oh and Tomonaâs first performance has the galvanizing effect of Bob Dylan going electric. In the movieâs most inspired stroke, the music festivals of Muromachi-period Japan are transformed into their own rock scene, complete with androgynously glammed-out musicians, head-banging crowds and, at one point, a gorgeous projection of a giant, fiery whale. In its lengthy midsection, the movie essentially morphs into a concert film in which the performers unleash a series of banger ballads, each tune excavating a story about the fallen Heike warriors, often set to a jolting we-will-rock-you beat. (The music is credited to the experimental musician Otomo Yoshihide.)

All this bold, heady arena-rock anachronism makes an intuitive kind of sense. Still, as a story about storytelling, âInu-ohâ can tend toward the diffuse. The busy, sometimes baffling plot hurtles forward in a welter of eruptive imagery, some of it dazzlingly up-to-the-minute, some of it done in a more primitive, inky style. This is not the first time that Yuasa, one of the more stylistically unfettered filmmakers working in Japanese animation, has employed a wide range of visual styles to tell a story, as he did in his 2004 debut feature, âMind Game.â (His other fantasy-themed features include 2019âs charming surfer romance âRide Your Wave.â)

But thereâs meaning in the filmmakerâs madness, and it isnât hard to suss out. Inu-oh and Tomonaâs friendship poses a threat to the ruling, warring imperial order, their creativity granting them a power that dictators can restrict but never themselves wield. And with each wildly applauded performance, Inu-ohâs physiognomy notably changes; he appears less demonically outlandish and more and more human, as if by restoring the humanity of the Heike clans he were also forging his own. Itâs an effective metaphor for the transformative nature of art in a movie that demands to be seen and heard, no less than the anguished, restless spirits it can barely contain.

âInu-ohâ

In Japanese with English subtitles

Rating: PG-13, for some strong violence and bloody images, and suggestive material

Running time: 1 hour, 38 minutes

Playing: Starts Aug. 12 in general release

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.