- Share via

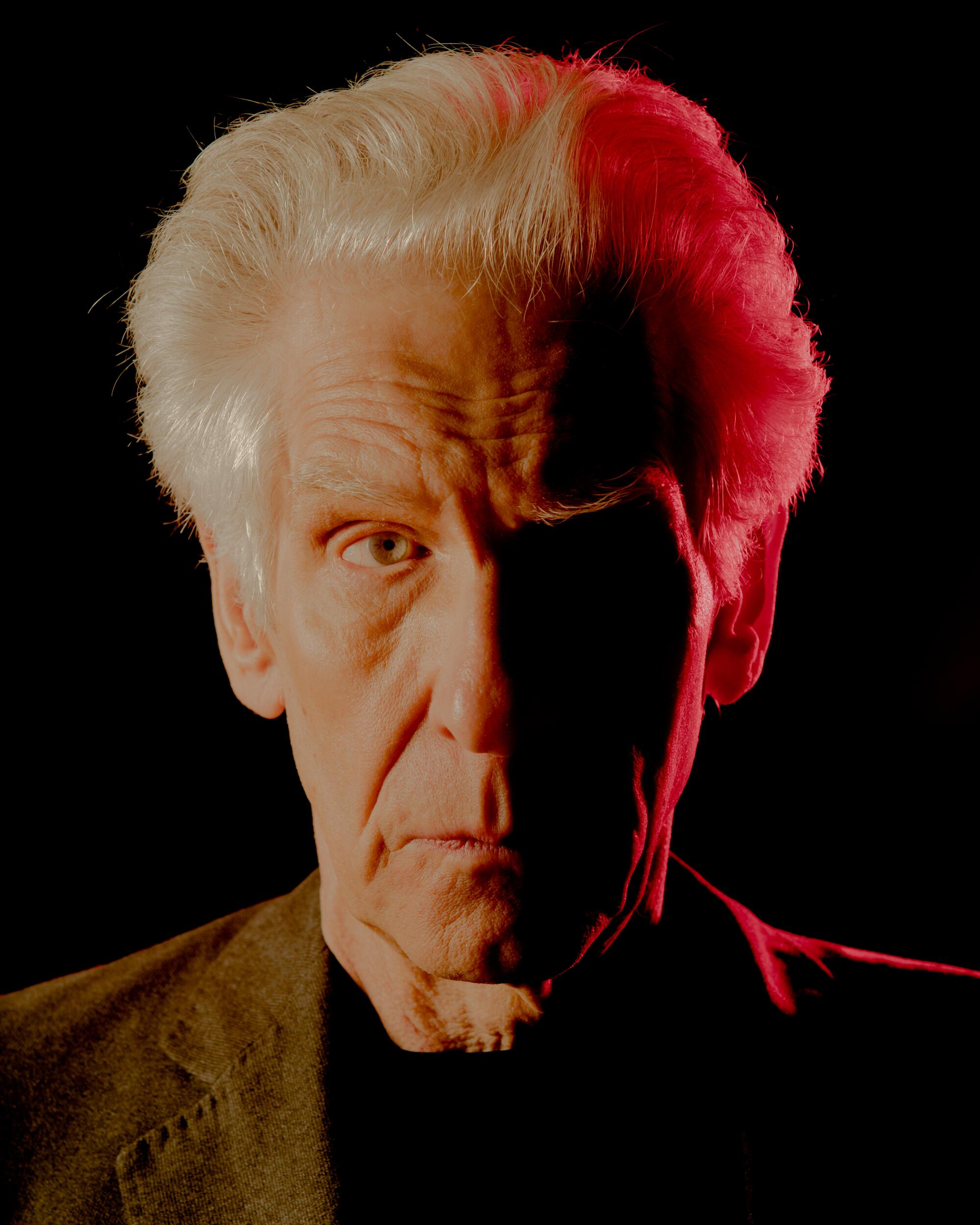

A remarkable number of the films by David Cronenberg could easily be called “Crimes of the Future.” In fact, he already used the title once before, on a short feature in 1970. His latest film, also called “Crimes of the Future” but unrelated to the earlier work apart from the title, continues his long fascination with the possibilities of the human body, explored in films such as “Videodrome,” “The Fly,” “Dead Ringers,” “Crash,” eXistenZ” and many others.

Cronenberg wrote the script for his latest “Crimes of the Future,” originally titled “Painkillers,” back in the late 1990s, and it was producer Robert Lantos who suggested both that Cronenberg return to the project and lift the title from the earlier film.

Set in an unspecified future, the film follows Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen, in his fourth Cronenberg film), a performance artist whose work involves the fact his body can grow new organs. His partner Caprice (Léa Seydoux) performs surgeries to remove them as public events. This gains the attention of two bureaucrats from the new National Organ Registry, Timlin (Kristen Stewart) and Wippet (Don McKellar), who both quickly become fans of Tenser’s work. The story also includes an underground alliance of people attempting to digest plastics as food, a cop from the New Vice Unit and a pair of service technicians who are also assassins. The film has a mordant sense of humor, a hypnotic gracefulness and a startling emotional sincerity. From a filmmaker who can lean toward the cerebral, it has an unexpected amount of heart.

Playing now in theaters, the new “Crimes of the Future” is Cronenberg’s first feature film in eight years, since 2014’s “Maps to the Stars.” That same year he also published his first novel, “Consumed.” Cronenberg, now 79, is set to begin shooting another project soon.

The movie feels like a summation of themes that you explored in many of your earlier films. Did it feel that way when you wrote it more than 20 years ago?

David Cronenberg: No, it definitely didn’t. I know people find this hard to believe because, of course, after you’ve made the film, the connections with other films that I’ve done is pretty obvious. And if I had been approaching my script as a critic might approach a film, I would see those connections too, but I’m so focused on the movie, on the bubble that the movie is in and trying to make it come alive and be viable within itself. And of course, when you’re making the movie, you’re worried about the actors, the costumes, the locations, you’re not really thinking about your other movies because that actually doesn’t give you anything creatively.

So basically what I say is it’s not a self-referential film because I’m not thinking that when I’m writing it or directing it, but the connections are there because my nervous system, such as it is including my brain, is the substrate of everything I’m doing. So I might even say in the Burroughs-ian way that all of my work and all of my life is one thing. In which case, it now makes perfect sense that there should be these connections.

Did you mean to take a break from filmmaking?

Cronenberg: Yeah, at a certain point I thought I just didn’t need the aggravation. I even said to my son [Brandon Cronenberg], who as you know is a film director and writer, I said, “I’m just not willing to suffer anymore.” And he said, “Well, I am willing to suffer.” And I said, “Well, that’s good because you are going to suffer.” And he has, to get his movies made. But I guess I wasn’t willing to suffer. And my life had changed, my wife of 43 years had died and she had been with me right from the beginning. So I thought maybe I’d write another novel. I didn’t feel that I would stop being creative. I just thought I wasn’t going to make movies and every time I read something about some horrific thing that happened in Hollywood, I’d say, I’m so glad I’m not doing that anymore. When I say horrific, I mean industry kind of stuff.

There’s a line in the movie where Viggo says, “I thought I was tapped out.” Did you feel that way? Is that you talking there?

Cronenberg: Well, don’t forget, I wrote that when I wasn’t tapped out and it was 20 years ago. The script did not change one word, I did one draft and we went in to shoot with that draft. It didn’t change. Other than the things that change when you are actually making a movie, like suddenly we’re shooting Athens, I couldn’t have anticipated that. And so I embraced Athens in the texture of it and all that. Viggo likes to provoke me by saying it’s my most autobiographical movie. And I think he means in that way as an artist, not because it has incidents in it that are from my life. And so not in the usual sense of autobiography, but in that sort of metaphorical sense that he meant, I can accept.

Lines like that, as I say, I wasn’t thinking that way, but still that’s a line in the movie and you have an artist who is giving everything he’s got from the inside out to his audience. And I think that Tenser is the analog or the avatar of a passionate, intense artist who is giving absolutely everything and allowing himself or herself, theirself, to become as vulnerable as you are. In fact, when you create art and you unleash it on the world, sometimes it unleashes other things back at you.

And whether 20 years ago or now, do you feel like we are evolving? Do you think that humans are reaching our next phase, that we’re moving forward?

Cronenberg: Well, when you say moving forward, that’s a misunderstanding of evolution. Certainly in the Victorian era, when Darwin first started to propose evolution and people gradually began to accept it, and certainly if you’re Karl Marx, you thought that there was an evolution towards a better creature, but evolution isn’t about becoming a better creature. It’s just becoming a creature who is more capable of existing in an environment. It doesn’t mean that this creature is more beautiful or stronger or more morally sound or anything. So for me, it’s obvious that we are in fact evolving. We’re completely wired differently than somebody a hundred years ago because of technology. And then of course there’s the microplastics thing and all of the toxins, but also nontoxins, the strange chemicals that are in our body, that our cells are trying to figure out what to do with. We are definitely evolving. It just doesn’t mean that we’re evolving to be better creatures, though. I think all you have to do is look at the news and you know that’s not happening. So yes, we are evolving.

Due to the timing of the movie’s release, a number of reviews are comparing the film to what’s happening here in the United States regarding women’s reproductive rights and Roe vs. Wade. How do you feel about that?

Cronenberg: Well, I think it’s inevitable. If your movie is absorbed in a way that inspires thought of a certain kind or reinforces some political stance, I think that’s great. It means your movie is alive and it’s part of the zeitgeist. If it’s just sort of a little entertaining, something that disappears instantly, then for me that’s a disaster. But whether I would approve of the particular political stances or not, well, who knows, that’s another interesting discussion. And I’ve certainly made some comments about that in the press, as you’re probably aware of. Because the movie is about control of bodies and about governments who try to control bodies and it’s not pretty.

That helps to reconcile that the movie is about human bodies evolving at a time when our human society seems so much to be taking steps backward. As you said, evolution does not necessarily mean a step forward.

Cronenberg: Yes. It means change, but it doesn’t mean necessarily positive change.

You’ve been exploring ideas about the body and technology for a very long time. I’ve heard you talk a number of times about your recent eye surgery. That seems to have really changed your view of the world.

Cronenberg: Literally. Technology, as I’ve said endlessly, is really a reflection of what we are and it’s all this good stuff and it’s horrifying stuff. One of the good things is that if it weren’t for my hearing aids and now for my cataract surgery, I wouldn’t be making movies. In terms of hearing, my career would’ve ended 10 years ago. So as an artist, I am thankful for that technology. And yes, I am bionic. I have plastic lenses in my eyes and little computers stuck in my ears. What can I tell you? But the thing is that I have kind of anticipated this, my mother was a musician and her brother was a musician and they both ended up with hearing aids. It was going to happen to me for sure. And my sister, same thing.

So being aware of the body for me is the essence of what we are. I don’t believe in an afterlife or a spirit that lives aside from the body or anything like that. So for me the essence of what we are is the body. And therefore, I’m always amazed when people say, “Why are you so obsessed with the human body?” And I say, “Well, I’m not really obsessed, but I can’t imagine not being interested.” How can you not be interested? It is the essence of what we are and I think any artist, the game is you are exploring the human condition. You’re looking at what it is and where we are within it and what it means to be human.

And that means the body, starting with the body. And so that’s always been the case for me. It was very intuitive. When you’re forced to be articulate about it, you start to have to think about it rationally and so on, and that’s what I’ve come up with. But basically I’ve always thought that. In the movie, there is the mantra — “Body is reality.” That is literally true. I mean, you change your body, you change your reality. I can tell you that with my hearing aids and with my new eyes, because colors are different, light is different, resolution is different with these new eyes. So the eyes that I’ve been making movies with for 50 years are gone. They’re gone. These are new eyes.

As I understand it, your next project, “Shrouds,” is something that you originally conceived of as a series for a streaming service and they didn’t want it. And so you’ve reconfigured it as a feature film. I’m so struck by the fact that you tried to play along with what contemporary Hollywood wants and then they didn’t want it. How do you reconcile that?

Cronenberg: Well, it’s such a familiar experience for me because there was a time when I was trying to do a “Scanners” TV series because CBC, NBC, I think I met every major network at the time and they were all interested in it because “Scanners” surprised everybody. This little low-budget horror film that was shot in Canada was like the number one film in North America suddenly on the Variety charts. Everybody was saying, “What the heck is this? Let’s get this guy.” And then I go in for meetings and they’d say, “Well, of course we can’t have exploding heads and we can’t have this and we can’t have that and we can’t have that.” And by the end of it, they said, “Well, you know what? We don’t want to do it. It seems kind of boring.”

And I said, “Well, you know why it’s boring is because you’ve removed everything that was interesting about it. Everything that made the movie successful you’ve said you can’t do.” So I’ve had the experience many times of people say, “We love you. We love your work. We really want to do something with you, just not this,” whatever it was I was proposing. And in essence that’s what happened with Netflix. I wondered if they would be different or I’d have a different experience. And I was very impressed by their success. And I was very intrigued by the phenomenon of streaming and streaming series. And I still think it’s really an interesting thing, it would’ve been a different kind of filmmaking for me, maybe directing the first two episodes and then just overseeing the writers of the rest and it would be unlike anything I’ve done. But it was not to be, it’s basically the same thing, “We love what you do and we want to work with you, but just not this,” basically. As the French say, “plus c’est la même chose.” The more it changes, the more it’s the same thing.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.