From the Tom Brady roast to WWE: What it means when Netflix turns to live TV

If youâre like me, you may not have watched Netflixâs live roast of Tom Brady in real time. You also probably didnât watch every episode of âJohn Mulaney Presents: Everybodyâs in L.A.â right when the offbeat talk show was running on the streaming service. But you probably heard about the jokes on social media, saw clips online and maybe went back to watch later.

Or perhaps you actually tuned in, just as you would do if this were the era when live viewing was pretty much the only kind available, unless you remembered to set your DVR.

Either way, itâs all good for Netflix, which is increasingly looking to the buzz that comes with splashy live events to drive more eyeballs to its platform of 270 million subscribers. The company that helped cement the binge-watching habit for viewers around the world has leveled up its foray into old-fashioned appointment television, with the most recent example being the companyâs deluge of content from its âNetflix Is a Jokeâ comedy festival in Los Angeles.

Netflix hit some speed bumps when it first started playing around with live programming, as with last yearâs âLove Is Blindâ reunion, which was marred by technical glitches. But the company recovered from that misstep and has since found its footing in the format.

Katt Williamsâ âWoke Fokeâ stand-up special early this month was the No. 2 Netflix show in the U.S. during the week it debuted. âThe Roast of Tom Bradyâ caught fire on social media with its endless jokes about the NFL greatâs divorce from supermodel Gisele BĂźndchen. Mulaney went viral with his monologue about the weird geography and character of L.A., set to a cartoonish map of its famously eclectic neighborhoods (inaccuracies aside, it was a solid routine).

Comedy may be where the strategy finds its stride, but Netflixâs ambitions clearly donât end there. The company has used its success with F1 racing (after the hit docuseries âFormula 1: Drive to Surviveâ) to springboard into live sports-adjacent entertainment with Novemberâs Netflix Cup golf tournament, featuring F1 drivers. The firm followed up with the Netflix Slam tennis event.

In January, Netflix and WWE signed a deal to move the flagship weekly wrestling series âMonday Night Rawâ to the streamer from NBCUniversalâs USA Network, starting next year. Before then, lots of eyes will be focused on Julyâs boxing match stunt between Mike Tyson and YouTuber Jake Paul.

And, as my colleagues Stephen Battaglio and Wendy Lee wrote last week, Netflix could soon land a big prize, as itâs in the running for the rights to two NFL Christmas Day games. If Netflixâs bid is successful, the pigskin matchups would be the first major professional league sports events carried by the Los Gatos, Calif.-based giant.

If those efforts succeed, they could give Netflix the confidence to bid more aggressively for actual sports league media rights, an area it has been tepid about pursuing, compared with streaming rivals such as Apple (which has MLB Friday night games) and Amazonâs Prime Video (which streams Thursday pro-football matches).

âThis is going to be great learnings for them,â said Jeffrey Wlodarczak, a media analyst with Pivotal Research. âItâs still a little bit of an experiment. WWE, maybe not, but that was a good price for a long-term deal and decent flexibilities, so it still qualifies. Everything theyâre talking about doing is dipping their toes.â

Netflixâs caution about sports rights bidding wars is understandable. For one thing, itâs an expensive arena in which to compete, in part because the market has been driven up by so many new players backed by cash-rich technology businesses.

The NBA is expected to announce a new game-changing multiyear media rights pact that reportedly will more than double its annual fees to $6 billion after the 2024-25 season.

Prime Video is expected to get an exclusive package of games, adding to its sports portfolio. Walt Disney Co. is expected to retain NBA rights for ABC and ESPN. Comcast, meanwhile, has shaken things up with a $2.5-billion bid for a package of games for Peacock and NBC. All this has put Warner Bros. Discovery in a difficult position. It canât afford to lose the NBA on TNT, so it will probably end up paying a lot more for fewer games.

Netflix can afford to duke it out with the legacy media firms, but it will want to pick its shots based on what it learns from its more modest efforts. âWeâre not anti-sports,â Netflix co-Chief Executive Ted Sarandos said in 2022. âWeâre just pro-profit.â

Traditional sports programming also runs counter to Netflixâs dominant philosophy, which places huge value on having its original shows and movies live forever on the platform. You might go back and watch those clips of Nikki Glaser ripping into Brady at the Kia Forum. But youâre probably not going to watch an NFL Christmas game after it streams.

Companies that pay for sports rights are really renters, not owners.

Still, there are compelling reasons why a bigger sports push by Netflix is likely, if not inevitable.

For one thing, Netflix is trying to expand its advertising business, which has taken off at a gradual pace so far. Ad buyers love sports because itâs one of the few categories that actually gets viewers to tune in at certain times. Netflix, by the way, holds its upfront presentation for advertisers Wednesday in New York.

Also, while the company is by far the global leader in subscription-based streaming, it has a lot of room to grow in terms of total viewership, accounting for less than 10% of TV viewing in the U.S., according to Nielsen (YouTube is actually bigger when it comes to viewing hours). A couple big live sports events could certainly increase its share of viewership.

âIf you want to move everybody off of pay-TV, go after sports,â Wlodarczak said. âItâs not just Netflix; everybodyâs probably going to move in that direction. You have to have massive scale, you have to have other businesses to offset that cost, which obviously, Amazon and Google do. And Netflix is just massive. Their scale allows them to do something like that.â

Big sports-dependent companies, such as Warner Bros. Discovery, Disney and Fox Corp., know this is coming. Thatâs why theyâre teaming up on an as-yet unnamed joint venture to stream their sports content.

Netflixâs aim is to be the first place viewers go to find something to watch. Sports may be the last frontier remaining between the company and that goal.

Youâre reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

Shari Redstone was poised to make Paramount a Hollywood comeback story. What happened? Rather than leading Paramount to reclaim its place among industry titans, Redstoneâs tenure atop the company has been marred by miscalculations and setbacks.

Court is the final frontier for this lost âStar Trekâ model. The 33-inch original model of the USS Enterprise from the 1960s TV series âStar Trekâ resurfaced decades after it disappeared. But then an auction house gave it to the son of Gene Roddenberry, and it became mired in controversy.

We checked in with Hollywood writers a year after the strike. Theyâre not OK. Film and TV writers of varying experience levels are struggling to find work after the Hollywood strikes amid an ongoing industry contraction.

Other news:

- LAist staffers offered buyouts ahead of possible layoffs

- Shohei Ohtani interpreter scandal TV series in the works

- SXSW to expand to London in 2025

- Netflix hires former Sony film exec Doug Belgrad

- TikTok sues U.S. government as ban looms

Theme of the week

âBundles are backâ

One of the most disruptive outcomes of the streaming revolution was the untangling of the cable bundle. Once each of the major traditional media companies decided to copy Netflix by offering its content Ă la carte, consumers had little reason to pay for a collection of channels they didnât watch.

The problem for the entertainment conglomerates was that blowing up the pay-TV bundle meant incinerating the fees that cable and satellite companies pay for their channels. Oops. Anyway, ever since, analysts have been predicting that the bundle would be reconstituted in some form, but online.

Now itâs starting to happen.

Warner Bros. Discovery and Walt Disney Co. last week announced their plan to offer a package deal for their streaming services, Max, Disney+ and Hulu. This summer, audiences will be able to get all three streaming services for a single payment, at a discount for what they would pay for the apps on their own.

The firms have not disclosed pricing for what theyâve called a âfirst of its kindâ between major rivals in streaming. (See our story on the news for more detail)

On Tuesday, Comcast Chief Executive Brian Roberts announced a plan for the company to create its own three-way bundle, called StreamSaver, that includes its own streamer Peacock, Netflix and Apple TV+ at a significant discount. The bundle will be available to Comcast broadband, TV and mobile customers, Roberts said at a media investor conference in New York.

Still, a re-creation of cable, this is not. At least not yet.

For one thing, the Warner Bros. Discovery-Disney team-up is a good example of a âsoft bundle,â which allows customers to access separate apps with a single payment. A âhard bundle,â in contrast, is where two or more services are merged into the same app. Examples of hard bundles are Paramount+ with Showtime. Similarly, Disney+ offers Hulu as a âtileâ on its app for people who pay for the Disney bundle.

Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery and Comcast are trying to reduce âchurn,â or cancellations. After a strong start, Disney+ has reached 117.6 million subscribers, adding 6 million during the most recent quarter. But its global total is still less than half of Netflixâs 270 million members.

Warner Bros. Discoveryâs direct-to-consumer services â Max, HBO and discovery+ â have 99.6 million subscribers combined, up by just 1 million from the same time a year ago. Both are also following Netflixâs lead by cracking down on password sharing.

All the streaming services have to get their churn under control if they want to raise prices, which, along with cost-cutting, is their path to profitability.

Big media players â especially cable companies like Comcast â understand that discounts can help stop people from dropping their services. If you make it too easy for customers to drop subscriptions, theyâll do so right after theyâre done watching whatever they signed up to see. Comcastâs StreamSaver deal is also a way to make its internet, mobile and television services more appealing to customers.

Streaming bundles, as theyâre being proposed now, donât have the power that cable once wielded to let the media giants over-monetize their content by getting consumers to pay for what they werenât watching. That era is over.

âThere will be re-bundling in the sense that there will be ways of giving consumers the flexibility to bundle stuff and save money, but I think any effort of forced bundling is not going to work,â Doug Shapiro, a former Turner and Time Warner executive and corporate strategy expert, told me last year.

What weâre seeing now is less of a restoration of the cable model and more of an admission that the legacy companies canât beat Netflix on their own.

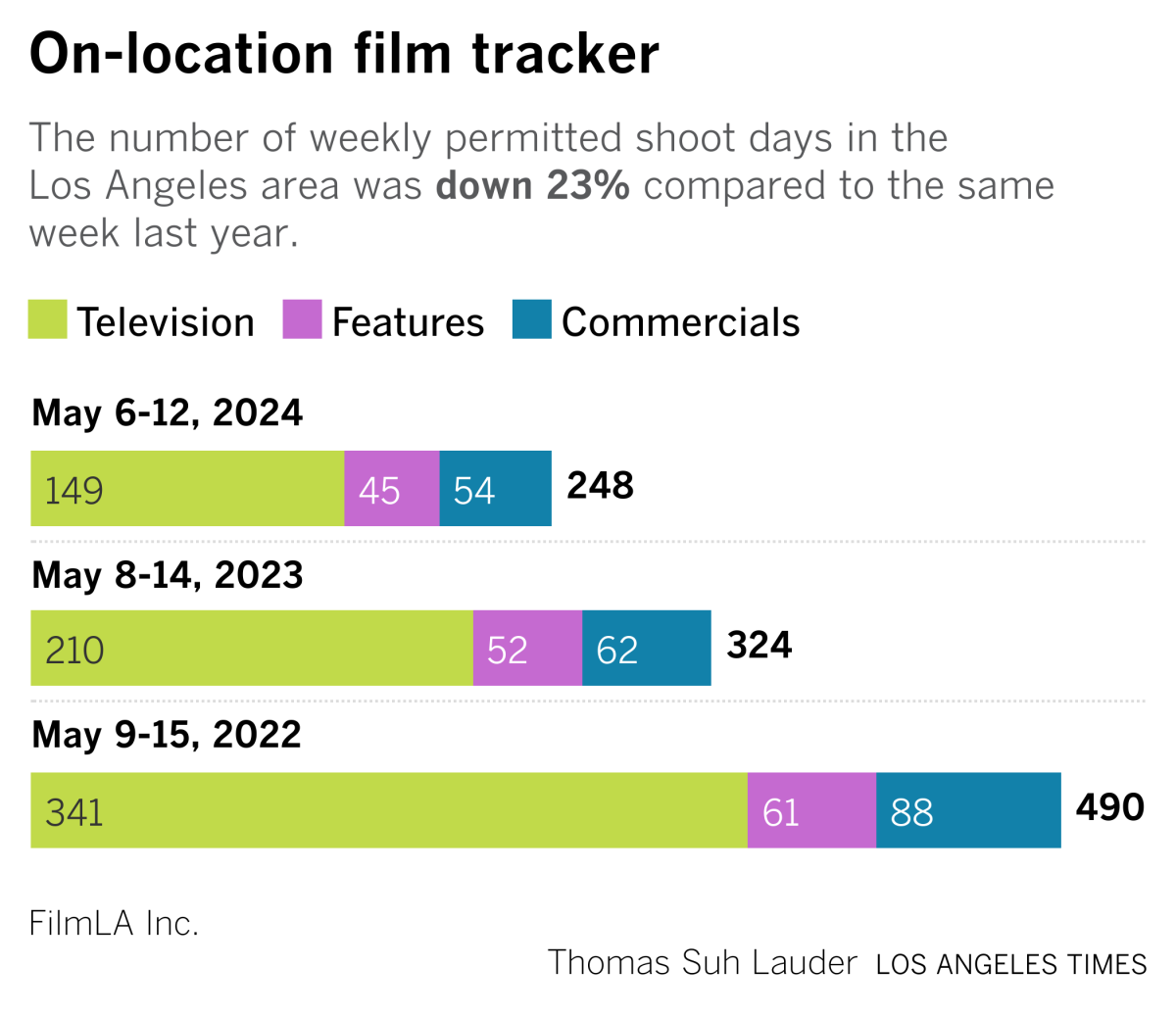

Film shoots

Film production was still way down last week compared with a year ago.

Best of the web

â Heâs back: GameStop, AMC stock soar as âRoaring Kittyâ meme trader resurfaces. Someone call Paul Dano for a âDumb Moneyâ sequel. (CNBC)

â Spotify to pay songwriters $150 million less next year due to audiobooks bundle. (Billboard)

â Ben Thompson rips on Appleâs horrible, no good iPad ad. (Stratechery)

Finally ...

Speaking of that iPad ad, apparently, when you do it backward, it makes something beautiful.

The Wide Shot is going to Sundance!

Weâre sending daily dispatches from Park City throughout the festivalâs first weekend. Sign up here for all things Sundance, plus a regular diet of news, analysis and insights on the business of Hollywood, from streaming wars to production.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.