‘Harry Potter’ set at an HBCU? LaDarrion Williams wrote the book he always wanted to read

- Share via

On the Shelf

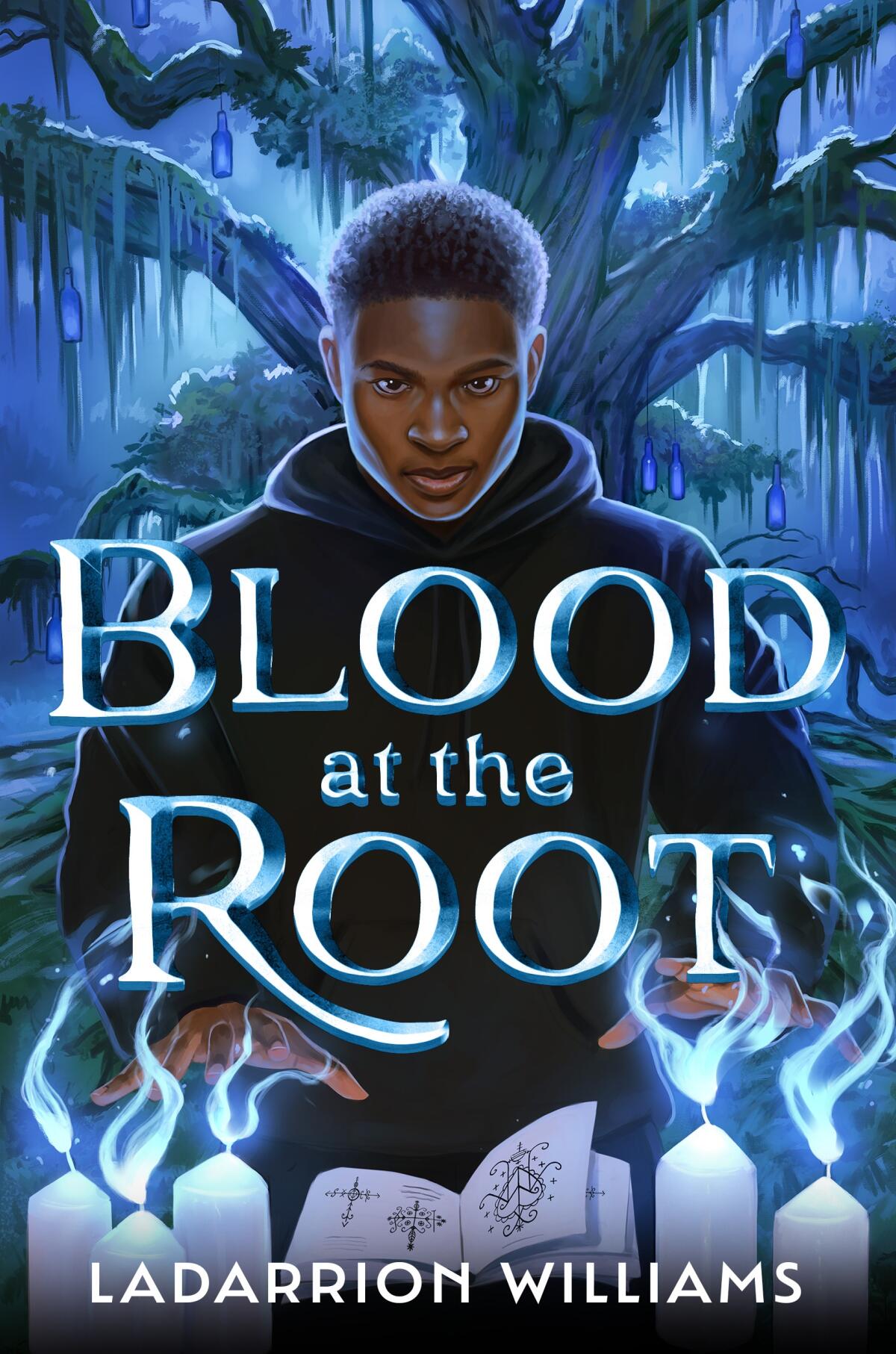

Blood at the Root

By LaDarrion Williams

Labyrinth Road: 432 pages, $21

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

LaDarrion Williams’ dream-come-true tale sounds like a Hollywood rags-to-riches film, about a kid from a small town who packs up and moves to Los Angeles to make his fantasy a reality, struggles and suffers but defies the odds and then some.

In Williams’ case, success has finally arrived with “Blood at the Root,” his first novel in a three-book deal, a series that centers on a Black boy in a young-adult fantasy saga — the kind of fiction he wishes had existed when he was a kid.

Tommy Orange was against revisiting Native American history in his new book. Why he changed his mind

Tommy Orange’s much-anticipated new book, ‘Wandering Stars,’ serves as both a prequel and a sequel to ‘There There.’

Williams grew up in Helena, Ala., a small town, but also a small world. And the world of publishing didn’t help much — he devoured the “Twilight,” “Harry Potter” and “Hunger Games” series but says, “I connected to the characters because it’s still a human experience, but I didn’t feel seen by those stories. And if somebody that looked like me was there, they were relegated to the side or killed to help propel the main white character’s story forward. Eventually, I fell out of love with reading.”

While attending a small Christian university in Tennessee, Williams double majored in writing and theater, but “there weren’t a lot of opportunities for people like me there — I was a 6-foot 3-inch, 250-pound Black kid and the only role I got was as a slave in ‘Big River.’”

Frustrated, he dropped out and returned home. But working at a Taco Bell drive-thru left him lost and depressed. Williams wanted to write plays or screenplays with strong Black roles, but there were no classes or other guidance at home. He knew he couldn’t afford a school like UCLA, so he looked up the syllabus for a writing class, bought the books and taught himself.

“I wrote my first pilot script, and people say to become a TV writer, you have to move to L.A.,” he recalls. On May 9, 2015, he was stuck at Taco Bell, dealing with rude customers, when his paycheck landed via direct deposit. “I had never been on a plane before but I looked up how to buy a plane ticket and bought one for $181, one-way, on Southwest. I packed up three suitcases and a dream and just moved to L.A.”

On the one hand, Williams felt tremendous freedom. On the other hand, there was culture shock, and he was quickly in over his head. “I got a job at Universal, thought, ‘Ooh, I’m going to be working on a movie set,’ but it was the theme park, and I was taking out trash,” he says with a wry chuckle. “My dream was right there, but it was a million miles away.”

He was naïve enough to think that he could still get a job as a TV writer.

“I thought it was kind of like applying to Taco Bell — you send in your stuff and then you just get hired,” he says. “I’ve definitely been humbled.”

Memoirs by Kiese Laymon and John Edgar Wideman; essays by Darryl Pinckney and Mikki Kendall; masterpieces from Michelle Alexander and Claudia Rankine.

Still, lonely and frustrated, he plugged away, writing, submitting scripts to contests, working for Lyft and Uber to fund short films and produce his own plays.

“I couldn’t get an agent or anyone to look at my scripts, but I was very hungry and kept hustling,” he says, even when he was without a home, sleeping in the same car he was driving around in all day. “I was doing it to pay for my films and plays.”

At one point, he wrote and produced a 25-minute pilot of “Blood at the Root,” hoping to make it into a TV series. While he says he got a strong response on social media, Hollywood once again paid no heed.

Although he had been passionate about writing plays with roles for young Black men, “Blood” struck a different chord for him, bringing him back to his teen years when he yearned for a fantasy story in which he could see himself. That feeling was especially acute in 2020 after George Floyd was murdered, prompting marches and protests across America.

“Now, I had the fire back in me,” he recalls. So he went to the Barnes & Noble in Burbank and asked the clerk for a YA fantasy book with a Black boy lead but without racial trauma or police brutality — one that could provide escape for readers. The clerk brought him to the YA section and together they searched. “And she looked at me and I looked at her and she said, ‘Oh, we really don’t have anything.’”

In Emily Raboteau’s book of essays, ‘Lessons for Survival: Mothering Against “the Apocalypse,”’ her care for her neighborhood and her maternal care for her children are connected as she faces an uncertain climate future.

That sparked a “righteous rage” in Williams, and he locked himself in his apartment for 12 days to crank out the first draft. “The main character, Malik, wouldn’t leave me alone,” he says, “and I saw my book cover in my dreams.”

“Blood” tells the story of Malik, a 17-year-old who has been in foster care for a decade since his mom’s death. He was 7 when his mother was attacked, and he used magic he didn’t know he possessed, unsuccessfully, to try to save her. Malik later harnesses his powers to rescue his foster brother Taye from an abusive situation. They run away together. (Malik’s experiences and language skew toward the older end of a YA audience, while wide-eyed Taye, at 12, provides a more innocent character.) Malik meets a grandmother he didn’t know he had, and she uses her clout to enroll him at Caiman University, an HBCU for kids with magic — essentially a Black collegiate version of Hogwarts.

“This is a coming-of-age story,” Williams says, adding that he stuck to his plan to not play up racial trauma or police brutality. Instead, you’ll find Malik hugging Taye and expressing his love. “We don’t really get to see young Black boys be tender with each other, and it’s so beautiful because Malik never received that type of tenderness when he was a child. It’s something I’m just learning now in my 30s.”

Originally, Williams planned to self-publish but was persuaded to seek a bigger audience. After plenty of rejections, he found an agent. After another round of “nos,” on Jan. 19, 2023 (he remembers each important date), while he was driving for Lyft, he got the call from his agent that they had landed a publishing deal.

With ‘Cahokia Jazz,’ Francis Spufford tells an intricate, suspenseful and moving story that rises from the mists of America’s prehistory and morphs into an alternate version of America’s story.

“The main theme of the book is that the magic of resilience is in the blood, and I had that magic inside of me,” Willams says, adding that he had to come to L.A. to find it. “I wouldn’t have made it back home. I was so depressed. It even came to a point where I didn’t want to exist anymore because I wasn’t feeding myself artistically or creatively.”

Before he signed the contract, Williams had one demand. “My one non-negotiable was that there be a Black boy on the cover,” Williams says. “I want young Black boys in Alabama, Mississippi or Kentucky to walk into that bookstore and see that cover and say, ‘Yo, that kid looks like me.’”

They’re not going to be the only ones excited to see it on a shelf. “I’m going back to that Barnes & Noble in Burbank,” he says. “I took a picture of myself in the bookstore that day but I was depressed and forcing myself to smile. Now I’m going back there to take a picture of myself with my book.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.