- Share via

On the Shelf

Blackouts

By Justin Torres

FSG: 320 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Justin Torres has a decent excuse for taking 12 years to write his second book. Roughly nine years ago, the novelist was on a fellowship in France, trucking along on a draft about a young gay sex worker, when one day he lost the manuscript on a train.

“I lose everything all the time,” Torres, 43, explained during a recent interview in his office at UCLA, where he is a professor of English. “I’m trained in a certain kind of radical acceptance.”

In fact, he didn’t even feel resigned, he recalls. He felt free.

The move gave him cover from his editor to spend more time reading — Manuel Puig, Juan Rulfo and others — in search of the inspiration to try something completely different. “I really wanted to change the way I wrote,” he explained.

Justin Torres reflects on what happens when the one thing you’ve never lost finally disappears

The result is “Blackouts,” an experimental journey into the annals of queer history that is equal parts intergenerational love letter and homoerotic fever dream.

Torres’ first novel was a more straightforward affair. In 2011, then a recent MFA graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he had a splashy debut with “We the Animals,” a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story about three biracial brothers growing up in a chaotic lower-class household in upstate New York.

Over the next few years, the book was translated into 15 languages and adapted into a feature film starring Raúl Castillo. Torres toured all over the country, completed fellowships at Harvard and Stanford and secured tenure at UCLA.

Sitting at his desk inside the university’s Kaplan Hall, Torres exudes a professorial quality — even as he cops to the irony of being an academic despite having taken 10 years to earn a bachelor’s degree. Raised in a small town outside Syracuse, N.Y, he enrolled and dropped out of several universities during his tumultuous 20s in New York and the Bay Area.

Torres was working a shift at a used bookstore in San Francisco when he discovered the text that made “Blackouts” possible. Scattered throughout his office bookshelves are several copies of the aged, nondescript volume: “Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns.” Published in 1941, the report examined the lives of 40 gay men and 40 lesbian women; it was one of the few predecessors to Alfred Kinsey’s groundbreaking research into human sexual behavior.

For the record:

12:36 p.m. Nov. 9, 2023An earlier version of this article stated that writer Justin Torres had never graduated college. Torres has a bachelor’s degree.

While writing and then promoting “We the Animals,” Torres found himself coming back to his complicated feelings about the study, which offered a glimpse into how the scientific community tried to understand queer people — even as it alienated them as subjects.

“He already had the seeds of this book in mind,” said Jenna Johnson, who edited both “We the Animals” and “Blackouts.” “It was germinating.”

After picking up Justin Torres’ debut novel “We the Animals” in the recommended section of a Manhattan bookstore, director Jeremiah Zagar knew almost immediately that he wanted to adapt it for film.

Torres said he was struck by the clinical writing style in “Sex Variants,” which he found dehumanizing. “If you look in queer history, so much is involved in this kind of medical, pathological readings of queerness itself,” Torres said. “You can’t look at our history and pretend that homosexuality wasn’t [considered] a mental illness until the ‘70s — you can’t ignore that.”

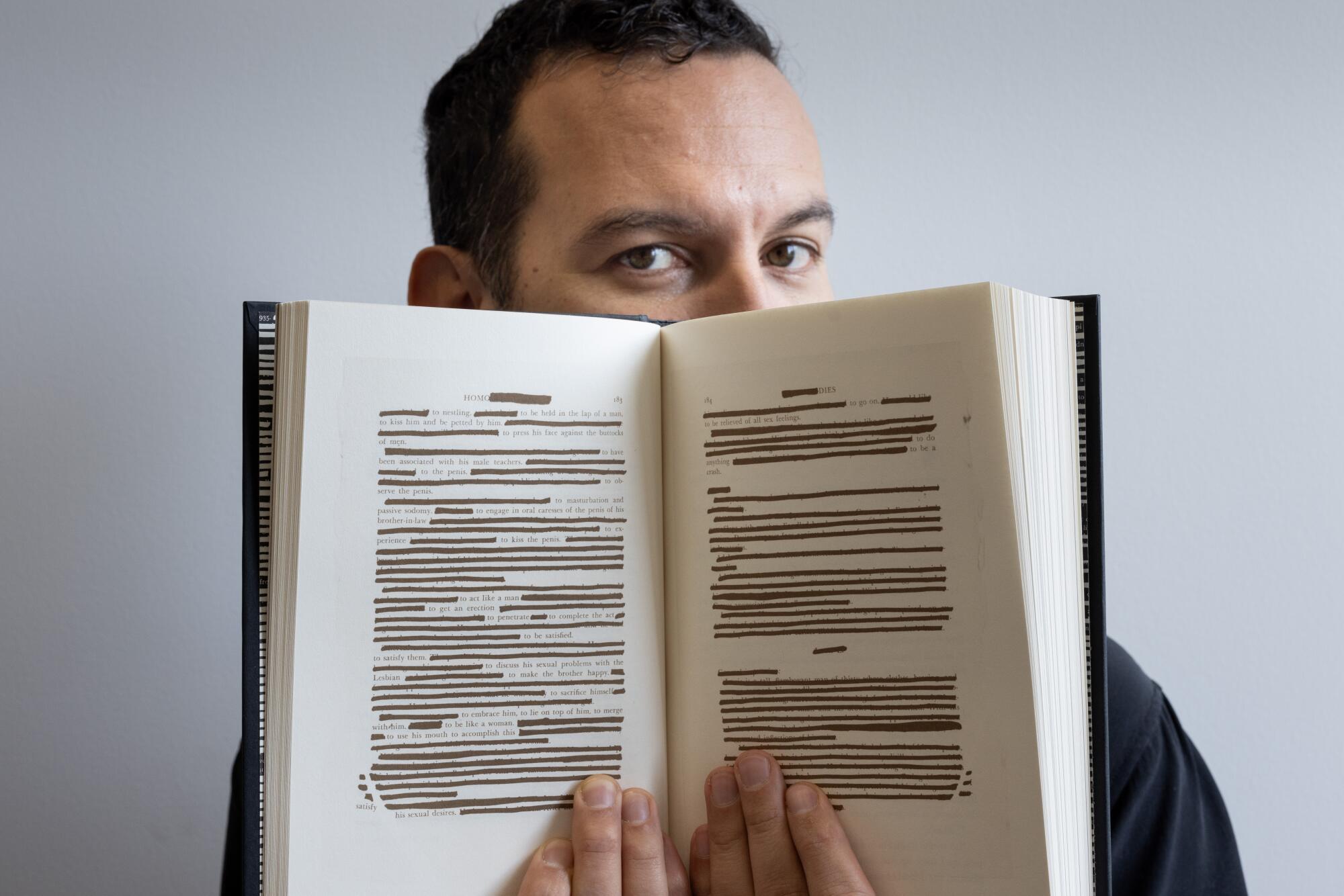

So Torres decided to perform his own erasure, crossing out the pathologizing language in “Sex Variants” and then crossing out more, until all that was left were words and phrases born into an entirely new context: a line of verse.

The heavily redacted poems — an example of what’s known as “erasure poetry” — became the titular “Blackouts” of Torres’ second novel, which follows a young male narrator in conversation with Juan Gay, an aging, erudite gay man on his deathbed. Gay was raised by Jan Gay, a real-life sexologist whose research was heavily used but barely credited in “Sex Variants.”

A tribute to forgotten queer history, “Blackouts” forges a lineage with erased trailblazers. And though it isn’t autobiographical, its themes of pathology and queerness are deeply personal; Torres was institutionalized for months just after he graduated high school. He declined to elaborate on the circumstances, but the experience shaped him profoundly.

In “Blackouts,” the narrator and Juan Gay first meet as inmates in a mental institution. After a formative encounter at the hospital, they go their separate ways until the narrator visits Gay at his home in the southwestern desert — a place called The Palace.

Scholar Anthony Christian Ocampo talks about drawing on his earlier years as a queer Filipino from Eagle Rock for his book ‘Brown and Gay in LA.’

The bulk of the novel’s conversations take place during Juan’s final days. Gay hopes the narrator will carry on the project of his life’s work: organizing and archiving pages of “Sex Variants” that unknown researchers had redacted, working to restore the voices and stories of Jan Gay and others.

…

A week before “Blackouts” was published in October, it was named a finalist for a 2023 National Book Award in fiction. (The winner will be announced Nov. 15.) Torres said the news was like “being struck by lightning in a good way.”

The recognition affirms “Blackouts” is a level-up for Torres, but the key to his work lies more in what it shares with his debut — elements of literary style and substance that were worked out not in classrooms, but through lived experience.

There is, for instance, Torres’ distinctive voice. Though the narrators of “We the Animals” and “Blackouts” sound completely different, they share a distilled lyricism that’s rare in contemporary prose.

“I always say he’s like a poet, because there’s such attention to detail to every single word,” said the novelist Angela Fluornoy, who met Torres when both attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has since become one of his closest friends.

Torres readily summons a specific story behind his obsession with craft. As a child in the 1980s, his family owned a word processor with a screen that allowed one to view and edit just a couple lines of writing at a time.

“The thing about writing fiction is you have total control, and every word matters, and you think so much about placement and order,” he said.

Curtis Chin grew up in 1980s Detroit around his family’s Chinese restaurant, Chung’s. In a new memoir, he explains how it taught him everything he knows.

Just as striking is the structure of his novels, both organized not in discrete chapters but rather as a series of vignettes — snippets of conversations and memories that shift voices, timing and perspective.

“The vignette is probably the consistent element that I’m sure will be across every book I ever write,” Torres said. “It’s just the way my mind composes narrative.”

Between each of its vignettes, “Blackouts” features dozens of images; some are the titular blackout poems, but there are also archival photos, diagrams and illustrations. The effect is of a dialogue not just between characters but between text and image.

“I think a big piece of figuring out how to tell this story was that sort of realization that this was a dialogue, a novel in dialogue,” said Johnson, his editor. “And that that dialogue was taking place outside of time.”

This dialogue also emerged from Torres’ personal life. In the acknowledgments for “Blackouts,” he credits David Russell, his partner, for inspiring the novel’s unusual structure: “I never would have conceived of writing a book that takes the form of one long conversation, if not for the fact that ten years ago we began a conversation we promised never to end.”

Russell, a literary scholar, is now a tenured colleague of Torres’ in the UCLA English department, but he taught at Oxford until earlier this year. Being in a long-term, long-distance relationship was not without its challenges, but it felt — as “Blackouts” does — like a dialogue outside of time.

Xuan Juliana Wang, another English department colleague who has known Torres since they were both at Stanford’s Wallace Stegner Fellowship, teaches “We the Animals” to her students for its distinctive second-person plural narration. But with “Blackouts,” she said: “It’s the language that carries you over — it keeps you hooked from page to page.”

There comes a time in every ADU story when you think you’ve made a terrible mistake.

Torres’ own experience teaching and working at UCLA — the research, the service, the mentorship — proved essential in achieving his stated goal of never writing the same way twice.

“I learned how to write” while working on the first novel, Torres said. “And once I figured out a certain kind of style, I was like: I don’t want to do this again.”

He feels that way, too, about “Blackouts” when it comes to his next novel, which he will embark on soon after he’s done traveling for the National Book Awards and a handful of end-of-year events. It’s tentatively called “The Rule of Three,” and just like “We the Animals,” it tells the story of three brothers. Though it might sound like a return to autobiographical material, with the characters now in their 40s, it won’t be a sequel, and it will be told in a completely different way.

Also, this time, he plans to back up his files — tempting as it may be to force himself to start over again.

“It’s easy to tell your editor ‘I lost a manuscript,’” Torres said with a laugh. “Everybody feels bad for you, and then you get to waste more time.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.